By Samantha Couture, MHS Nora Saltonstall Conservator & Preservation Librarian, and Lauren Gray, Reference Librarian

Welcome to Part 2 of our series on conservation at the MHS. The ability to perform conservation treatment is an integral part of providing access to our collections and making sure they will be available far into the future. We will discuss past conservation methods, how the field has developed, what conservation at the MHS has looked like, and the standards we adhere to today.

Book and paper conservation as a discipline is relatively new. Before the twentieth century, libraries and archives valued documents and books mainly for the text’s intellectual and historical content, rather than for the physical characteristics of the object. Treatments focused on repairs that were sturdy and allowed the item to be handled and read. It was very common to discard damaged bindings and other pages or inserts considered unnecessary.

However, there were individuals interested in the history that can be revealed by the physical characteristics of a book or document. William Blades, from Part 1 of this series, rails against bookbinders who routinely removed original bindings to trim the margins and put on new modern bindings. This was common practice, even at the MHS. One example in the MHS collection is William Bradford’s manuscript, “A ‘dialogue’ or the sum of a conference betweene some young men born in New England, and some ancient men which came out of Holland and old England 1648.” Sometime in the late 1800’s, this thin pamphlet was bound into a smart new Victorian leather binding with elaborate gold tooling. The fragile pages were sewn into a text of blank pages, but it made it difficult to see all the text, and turning the pages put a great deal of stress on the paper. We will look at how Samantha chose to treat this document later in our series.

In the 20th century, chemist and paper conservator William J. Barrow was very influential in the development of library and archives conservation. From the 1930s through the 1960s, he ran the W.J. Barrow Research Laboratory in Virginia. He collaborated with institutes such as the National Bureau of Standards and the Government Printing office. Barrow was an important link between the scientific and library and archive communities. He conducted many early accelerated aging tests, developed de-acidification techniques, and promoted the awareness of acid in modern papers and the damage it causes. [1]

Since Barrow’s time, conservation researchers have studied prevailing treatments and guided conservators in choosing the best methods. Conservators today need an understanding of the chemistry and materials used to reverse or slow the deterioration of paper. We have learned that many of our books and documents are stable without deacidification so long as the storage materials, building environment, and handling practices are suitable for long term preservation.

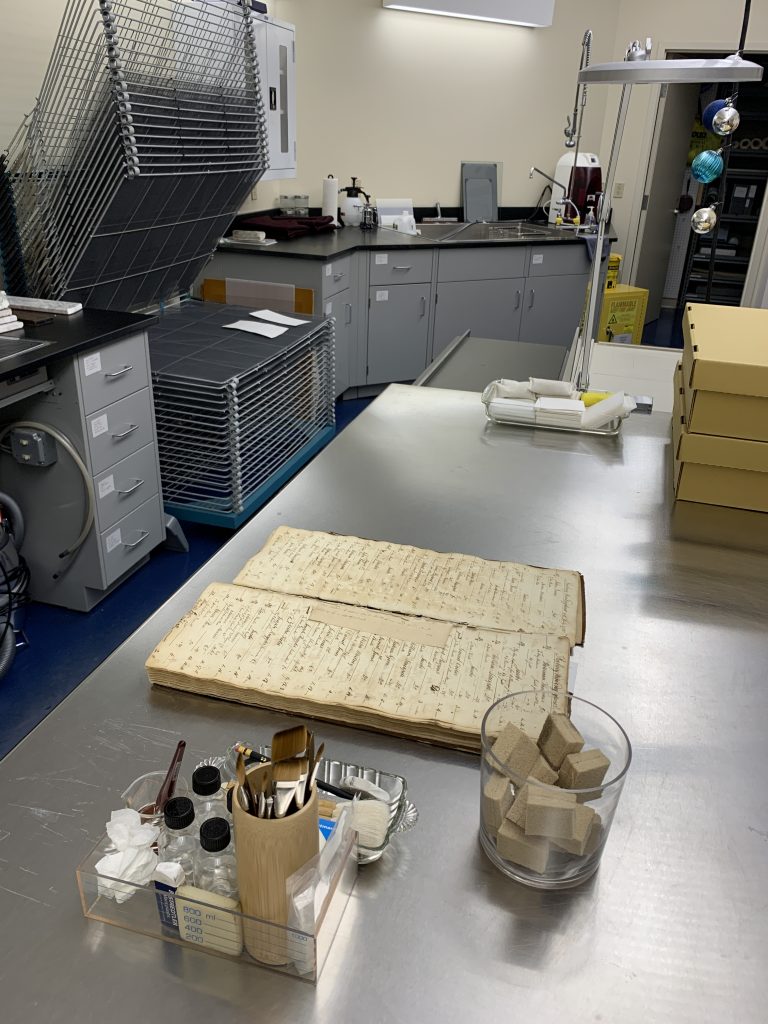

MHS has a long tradition of repairing manuscripts and books, which has evolved into today’s modern conservation lab. In 1837, a committee was formed to find “the best mode of preserving the manuscripts of the Society.” [2] In 1910, a bindery was created, and manuscripts were ‘silked’ (a technique that involved attaching sheer silk to support fragile paper) and bound into volumes. By 1972, the first conservation lab was built, allowing for the deacidification of manuscripts. [3] Anne Bentley, Curator of Art & Artifacts Emerita, was the paper conservator for the MHS from 1973 to 1998. During that time, she conserved many crucial documents, including the washing and deacidification of Thomas Jefferson’s manuscript for his book, Notes on the State of Virginia. She oversaw the creation of the second conservation lab built in 2000. Ms. Bentley continues to support the work of preserving our collections as a source of expertise and institutional knowledge.

Modern conservation practice is a blending of art, craft, and science. Many traditional techniques of book and paper conservation are still used, having been proven safe and effective by current research. Two presses from the original bindery are still used frequently in the lab. These sit alongside a chemical fume hood, a water de-ionization system, and testing and analytical tools to enable sophisticated and complex treatments of our archival material. Treatments follow the American Institute of Conservation’s guidelines and code of ethics, which emphasizes retaining original materials, using reversible techniques whenever possible, and documenting treatments with written reports and photographs.

In our next installment, we will look closely at a few examples of repairs and treatments in the lab.

[1] William James Barrow: A Biographical Study of His Formative Years and His Role in the History of Library and Archives Conservation From 1931 to 1941, Sally Roggia

[2] MHS Proceedings, ser. 1, vol. 2 (1835-1855), p. 96. (2)

[3] MHS Proceedings, ser. 1, vol. 2 (1835-1855), p. 96. (3)

Advisor: Paul N. Banks

Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Library Science in the Graduate School of Library Service, Columbia University, 1999