By Sarah Hume, Editorial Assistant

In 1797, a Kentucky merchant named Elijah Waters came forward with an important, yet extreme, claim: Gen. James Wilkinson, second in command in the Northwest Territory, was a spy. He was trading secrets to Spain.

Waters wasn’t the only one to make such allegations. For years, rumors had circulated about Wilkinson’s connection to Spain. Even Gen. Anthony Wayne, his commanding officer, accused Wilkinson of spying and led an investigation against him. Allegations were so widespread that John Adams wrote, “scarcely any Man arrives from that neighbourhood, who does not bring the report along with him.” (John Adams to James Wilkinson, 4 February 1798).

When General Wayne died on 15 December 1796, it seemed time for Wilkinson to escape suspicion. And yet rumors of treason continued and Wilkinson refused to lay low. Instead, he asked John Adams to continue the investigation.

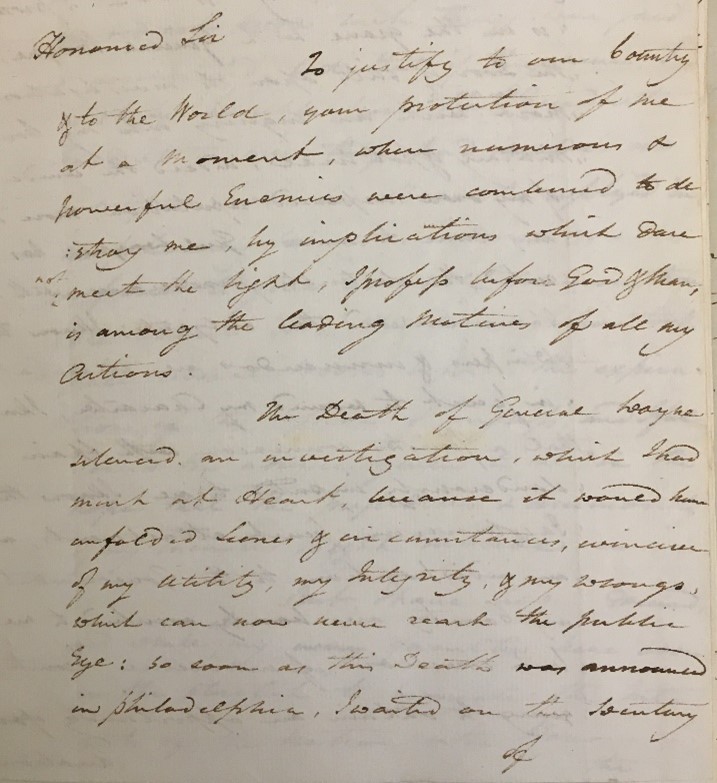

“Prosecution is in the grave with General Wayne,” Wilkinson wrote in his 26 December 1797 letter, “but the Door is still open to investigation, & I most earnestly wish an enquiry into my Conduct Military & political, indeed the vindication of my own aspersed reputation.”

Adams replied to Wilkinson on 4 February 1798, saying he did not believe either Waters’s claim or other allegations.

“We may be nearer than we suspect to another tryal of our Spirits; I doubt not yours will be found faithful,” Adams wrote. “I shall give no Countenance to any Imputations unless accusations should come, and then you will have Room to justify yourself; But I assure you I do not Expect that any Charge will be seriously made.”

Wilkinson never received an indictment from Adams. He went on to be trusted by the next two presidential administrations and died in 1825 having never been confirmed a spy. Only later would historians uncover his treasonous activities.

Like much of Adams’s correspondence in the Papers of John Adams, this brief exchange captures a moment of dangerous precipice. Had Wilkinson been more successful, he may have forever changed the American narrative. Exchanges between Wilkinson and Adams highlight the advantage we have as scholars: we know the end of the story. Reading correspondence allows us to see from an eighteenth-century vantage point instead. And though Elijah Waters may be only a passing reference in correspondence, history ultimately proves him right in the case of General James Wilkinson.

The correspondence between James Wilkinson and President John Adams will be included in the forthcoming volume 22 of the Papers of John Adams to be published Fall 2024.

The Adams Papers editorial project at the Massachusetts Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the generous support of our sponsors. Major funding for the Papers of John Adams is provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, and the Packard Humanities Institute.