By Emma Moesswilde, Georgetown University

Spring in New England seems, finally, to be just around the corner, with the promise of fresh food and sunshine after a long winter. Yet, with snow on the ground, it isn’t too hard to remember that late winter and early spring were historically periods of extreme leanness for European settlers living in Maine and Massachusetts in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The gap between the dwindling of winter stores and the advent of spring vegetable and dairy produce could be a daunting time for early modern cooks facing a scant larder.

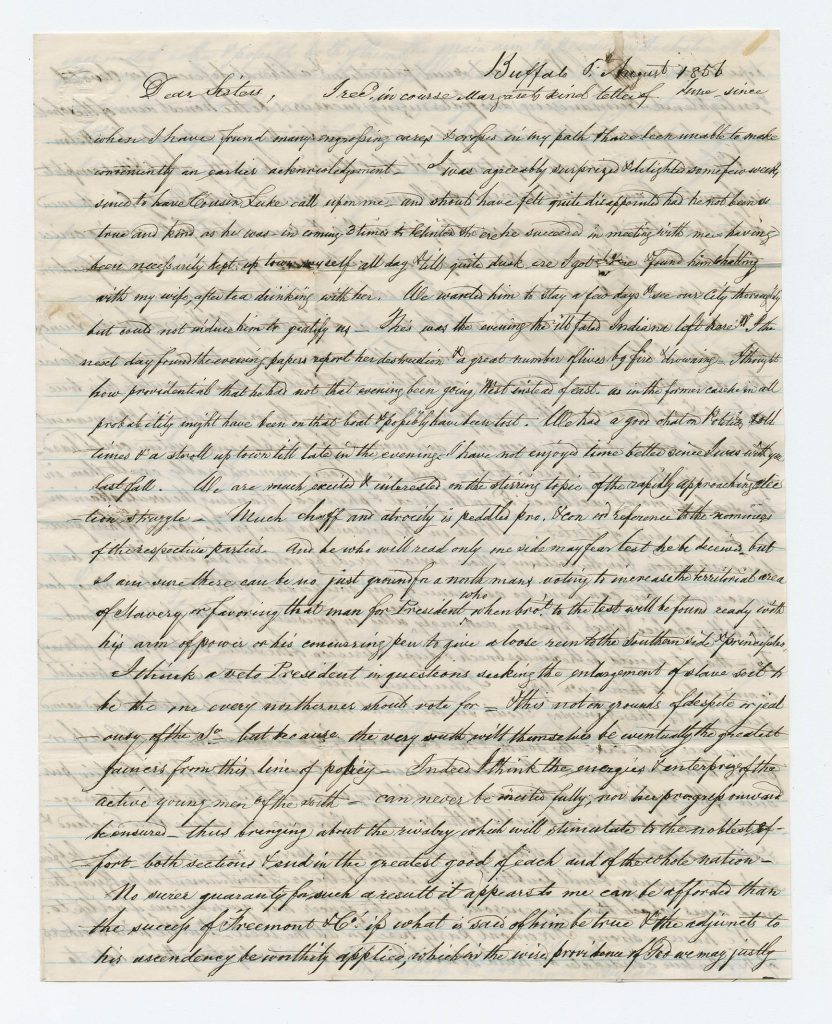

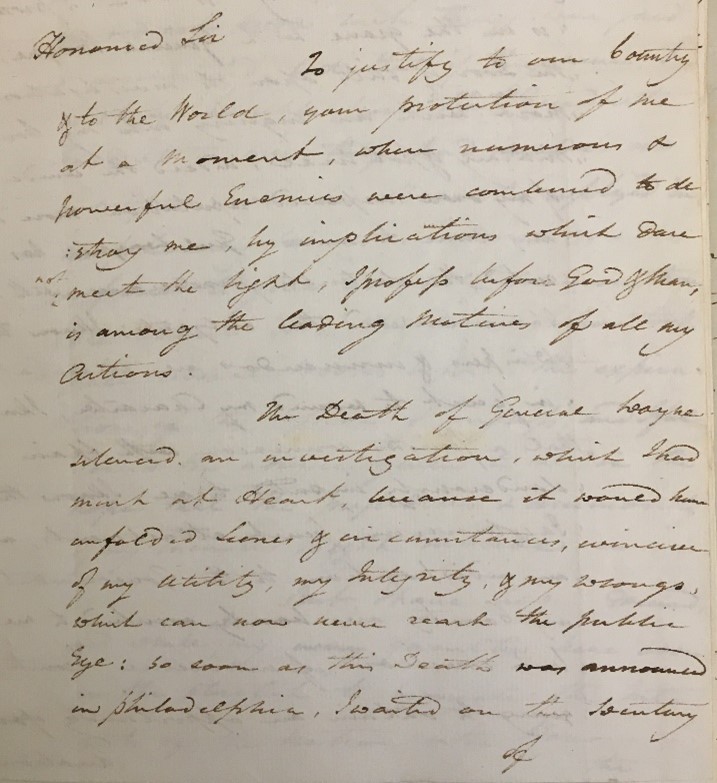

My research on seasonal variability and rural life in the British Northern Atlantic world has led me to examine the recipes that these cooks might have employed through the winter and early spring. Looking at manuscripts from the MHS collections has revealed a rich array of culinary knowledge recorded in the few published cookbooks of early America and the many manuscript recipe collections which maintained culinary knowledge across communities and generations.

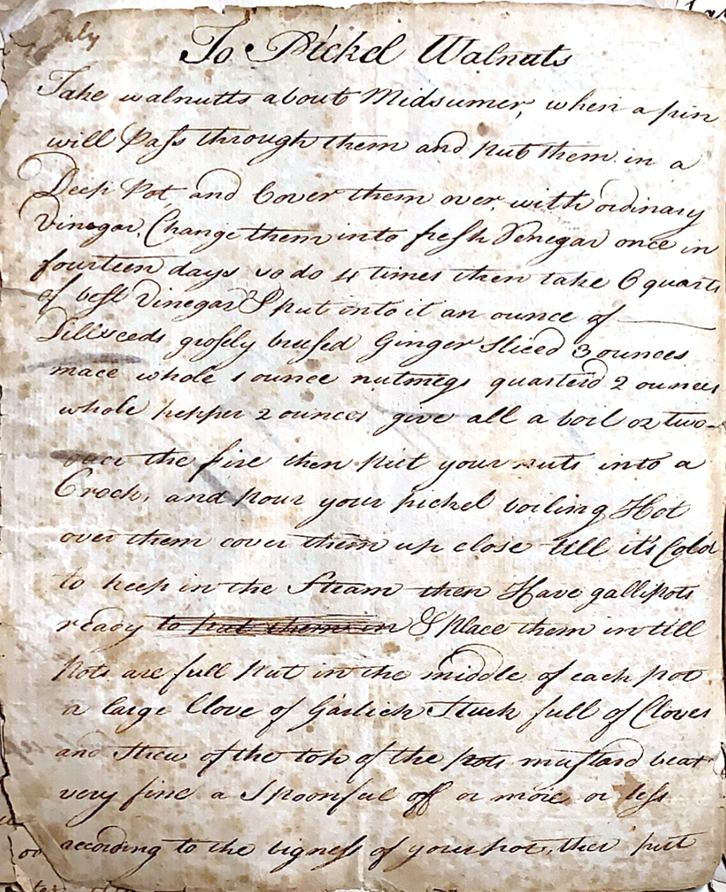

One of the most important ways in which early American cooks prepared for leaner seasons was through preservation practices. Even in periods of abundance, when the produce of fields, forests, oceans, and livestock filled the pot and the plate, those who worked in the kitchen looked towards leaner times by ensuring this bounty would be available to eat months in the future. My research in the MHS collections has found diverse recipes for preserving all kinds of rural produce. Walnuts, for instance, could be picked “about Midsummer, when a pin will pass through them,” and soaked in a mixture of vinegar, dill, ginger, mace, nutmeg, pepper, garlic, cloves, and mustard. According to an anonymous recipe book from around 1800 (Ms. S-835), the walnuts must be kept “under the pickel they are first Steep’t in or they lose their Colour” and could add interest to dishes throughout the winter as a “rellish with fish, fowl or Frigasy [fricassee, i.e., stew].”

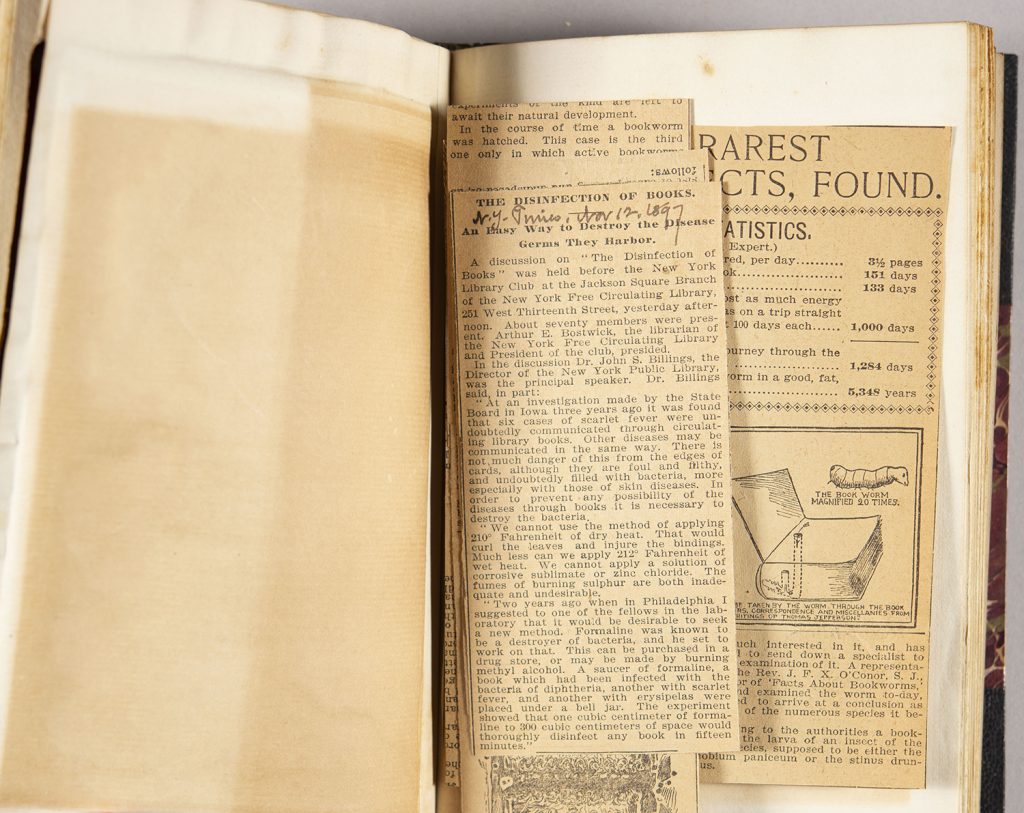

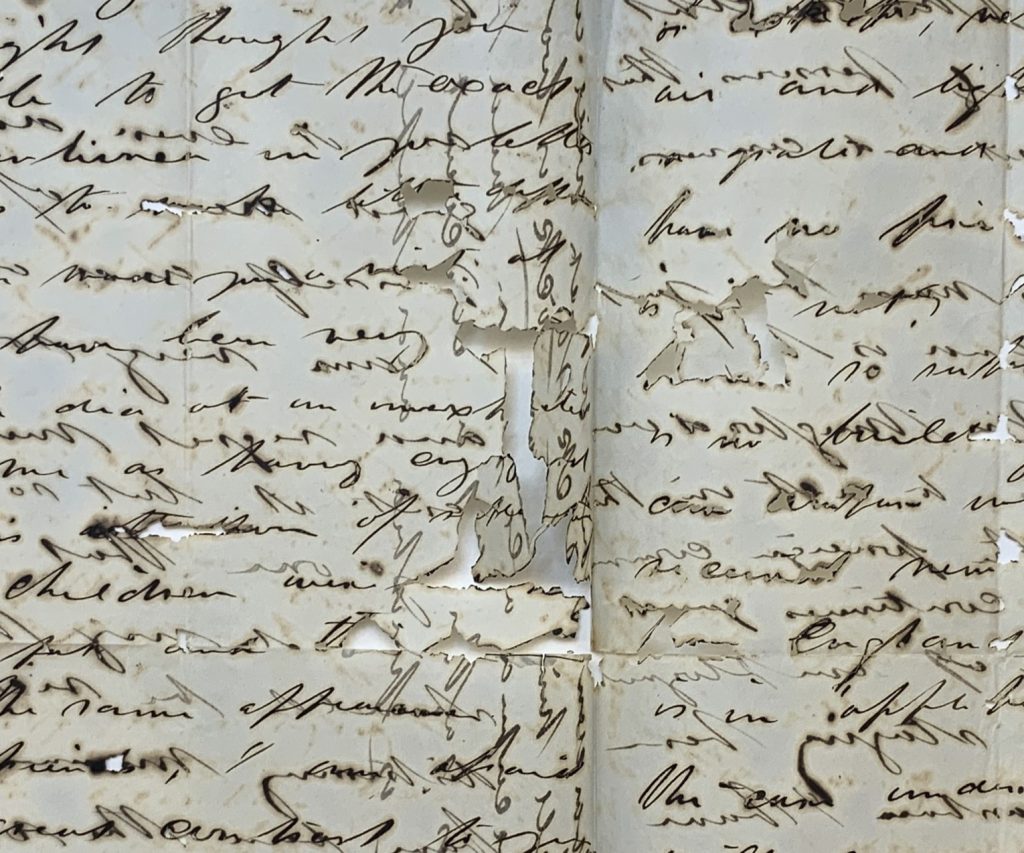

The development of preservation recipes preoccupied early American cooks and agricultural thinkers facing the challenge of food availability. Among the Vaughan family papers is a document entitled “Recipe for Preserving Butter” (Box 22, Ms. N-83, Oversize) which exemplifies the development of preservation techniques. Cooks interested in preserving butter (presumably for a season in which cows had run dry and were not producing milk) were instructed to beat sugar, salt, and saltpeter into butter “thoroughly cleansed from the milk” which could be topped with salt as a brine and “kept in pots of ten or twelve pounds.” “It requires then only to be covered from dust,” the instructions conclude. Yet below this recipe, more ruminations follow in the same handwriting: “If to be preserved several months — would it not be effectually secured from the air by pouring melted butter on the top so as to form a perfect crust?” The multifold methods for preservation ensured that cooks could put food by through a variety of methods, and for even longer periods of time.

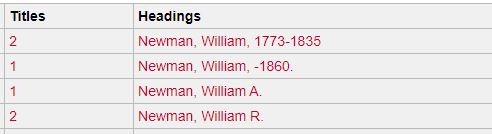

Preservation recipes also abound for meats such as bacon, fruit preparations such as preserves and vinegars, and the preparation of drinks such as cider, to name just a few. Recipes from the period are also rife with references to dried goods such as peas, beans, and salted fish whose storage was detailed in farming manuals like that of Samuel Deane (22450 Evans fiche). The broad expertise required to stock the early American larder is preserved in household manuscripts such as the recipe books of the Karolik-Codman family, which contain multiple types of handwriting and interleaved recipes that reference the knowledge of others, as in the case of “Mrs. Englishes receipt for Preserving Pears” (Box 4, Ms. N-2164). Such recipes provide insight into what may have stocked the pantries of early American cooks and ensured that, at least for most of the winter and early spring, some produce was still available. By the time fruit trees blossomed and fields thawed in April and May, bare shelves awaited another cycle of preservation practices.