By Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

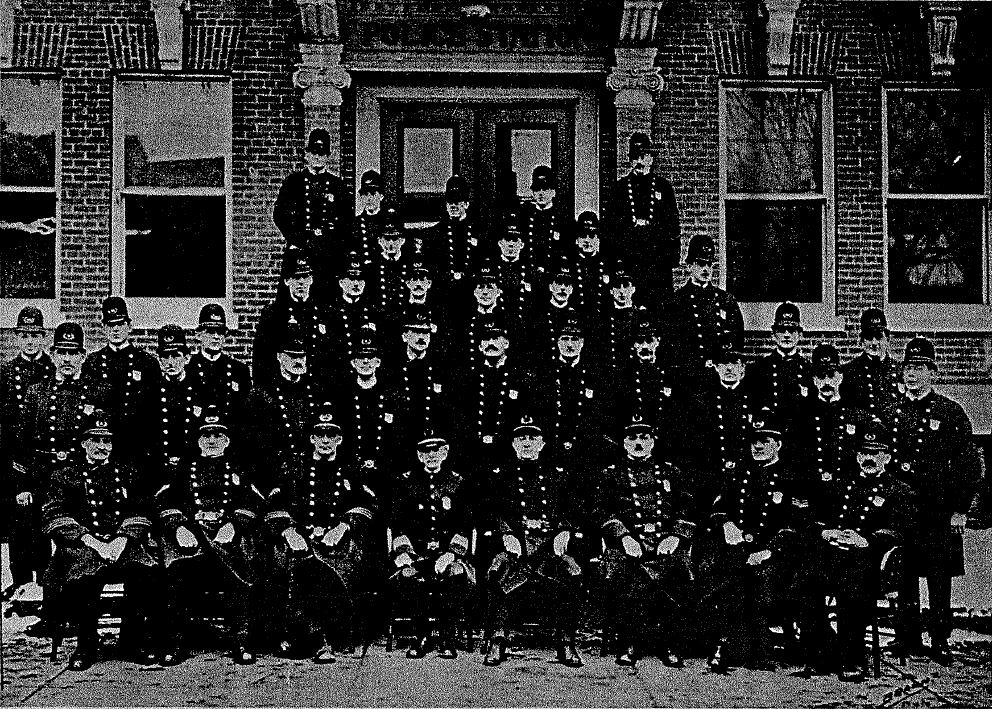

Previously on the Beehive, a colleague of mine described the early 20th-century diaries of Robert E. Grant, a policeman in the Hyde Park neighborhood of Boston. The MHS also holds the papers of another policeman, Lieut. James Bruce, a contemporary of Grant’s who lived and worked in Everett.

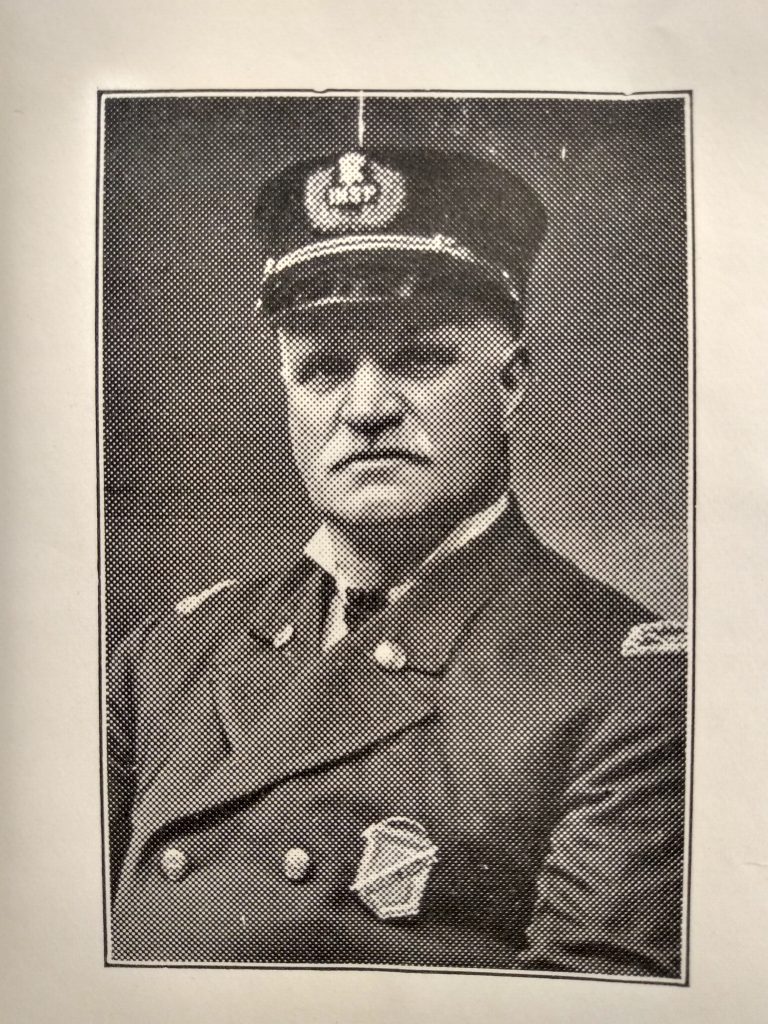

James Bruce was born in Scotland in 1869, immigrated to the United States in the late 1880s, and was naturalized a few years later. He and his wife (also a naturalized citizen from Scotland) lived at 10 Russell Street in Everett and had four daughters and two sons: Walter, Margaret, Janet, James, Mary, and Emily. Janet died as an infant.

When Lieut. Bruce was patrolling its streets in 1920, Everett’s population was 40,120. According to printed sources, the city was home to many immigrants, primarily from Ireland, England, Scotland, and Canada, as well as 1,129 African Americans.

Bruce’s collection at the MHS consists mostly of volumes documenting his police work, including two diaries, 1921-1922; a precinct arrest log, 1904-1924; and a memoir he wrote called Tattlings of a Retired Police Officer, printed in 1927. Some events described in Tattlings correspond to the log, although Bruce used pseudonyms for publication.

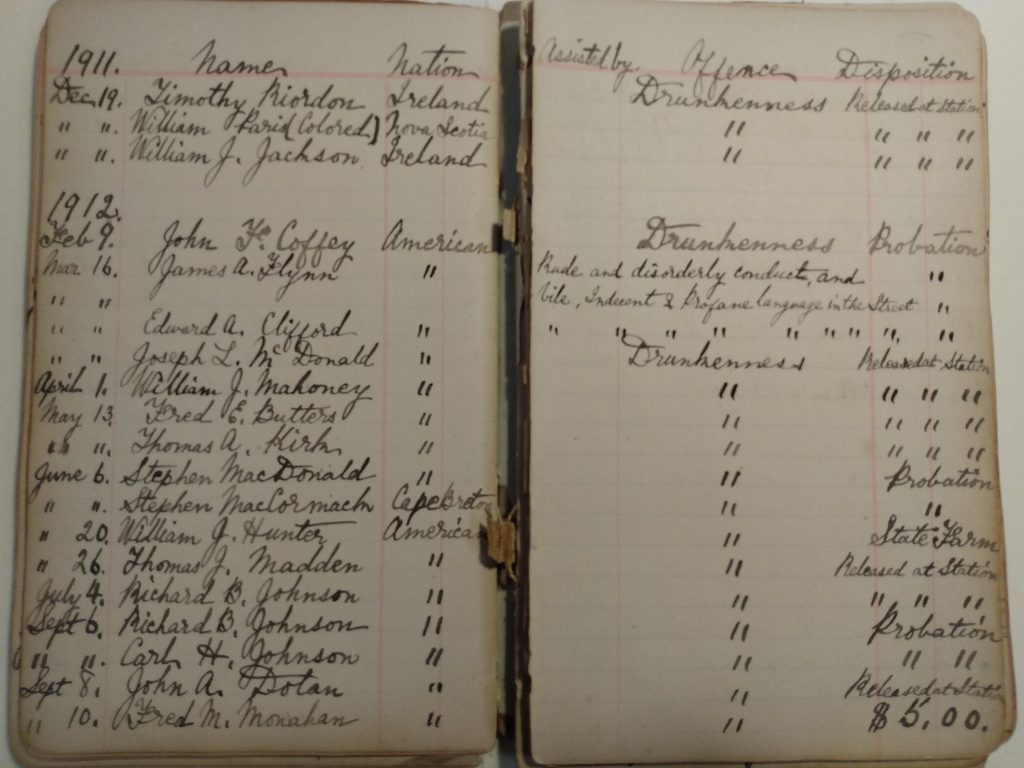

The arrest log, in particular, is a mine of information. Its pages are arranged into columns listing date, full name, nationality, “assisted by” (that is, who assisted Bruce in the arrest), offense, and disposition, or consequence for the arrestee. The first thing that stands out is how many people were arrested for drunkenness—so many that Bruce just used ditto marks to save time.

Other offenses included assault and battery, disturbance of the peace, larceny, breaking and entering, weapons charges, non-support of dependents, destruction of property, automobile violations, probation violations, and false fire alarms. Rare but still present were a few incidents of manslaughter. Some people were arrested for being ‘idle and disorderly” or “stubborn and disobedient,” “exposing his person,” or gambling on a Sunday. Adultery was also an arrestable offense.

And of course, those being the days of Prohibition, there were arrests for the manufacture and sale of liquor, though not as many as I expected.

Some entries are amusing: “vile, indecent & profane language in the street,” “indecent language near a dwelling” (which was worse, I wonder?), “lewd & lascivious cohabitation,” and “feeding [a] horse on [a] public st without an attendant or the wheels being locked.”

Many are disturbing: “two warrants for assault with intent to carnally know & abuse two juvenile females also one warrant for having in his possession obscene pictures for the purpose of corrupting the morals of the young.” Bruce also dealt with cases of incest, neglected children, mental illness, and animal cruelty.

When an arrestee was African American, Bruce indicated their race in a note next to their name. One Black man from the West Indies was arrested for “not having [a] registration card,” and another was AWOL from military service. I was also intrigued by some of the items that were allegedly stolen. Cash or a diamond ring, I understand, even “five hens,” but “four baby carriage wheels”?

James Bruce was injured in a fall in 1924 and retired from the Everett police force. He died in 1932.

In my research for this blog, I uncovered evidence of a shocking family tragedy. According to the Boston Globe, on 26 February 1922, James Bruce was handling his gun at home, apparently unaware it was loaded. The gun discharged, and the bullet struck his daughter Mary, a 17-year-old student at Everett High School. She died at the hospital six days later.

When I looked through Bruce’s collection for anything that might shed light on this incident, I found no reference to it, except by omission. The last entry in his 1922 diary was written on 24 February, two days before the shooting. The rest of the volume is blank.