By Kathryn Angelica, PhD Candidate in History, University of Connecticut

On December 14, 1899, the Massachusetts Historical Society received a collection of papers donated by Boston-born reformer Caroline Dall. An abolitionist, intellectual, suffragist, educator, and writer, Dall had a formidable reputation for speaking her mind. At the age of seventy-seven and living in Washington D. C., she sealed a number of trunks containing her life’s achievements. “At least I have lived to do this,” she wrote in her journal, “whether I shall finish the autobiography is doubtful.”[i] She included several volumes relating to her public career, reams of correspondence, copies of her published works, and “three trunks containing typewritten material, of which no public use [was] to be made until fifteen years after her death.”[ii] Plagued by ill-health, tragedy, and uncertainty for the majority of her life, she took an active role in ensuring the preservation of her life’s accomplishments.

Dall in fact lived another thirteen years until 1912, and although never completing her autobiography, was nonetheless able to curate the archive of her life. The Caroline Healey Dall Papers today span twenty four boxes and eighty-one volumes.[iii] Hidden within the collection are a series of annotations that do much to shape the narrative. On correspondence written between June 1834 and February 1863, for example, Dall made sixty-one annotations ranging from brief notes to paragraph-length reflections. One letter from 1842, written to the students of West Parish School while she taught in Washington D.C., contains notes dated 1878 and 1896. Footnotes on this selection of material are dated from 1856 to 1899, suggesting Dall routinely pored over correspondence from decades past, drawing different conclusions.[iv]

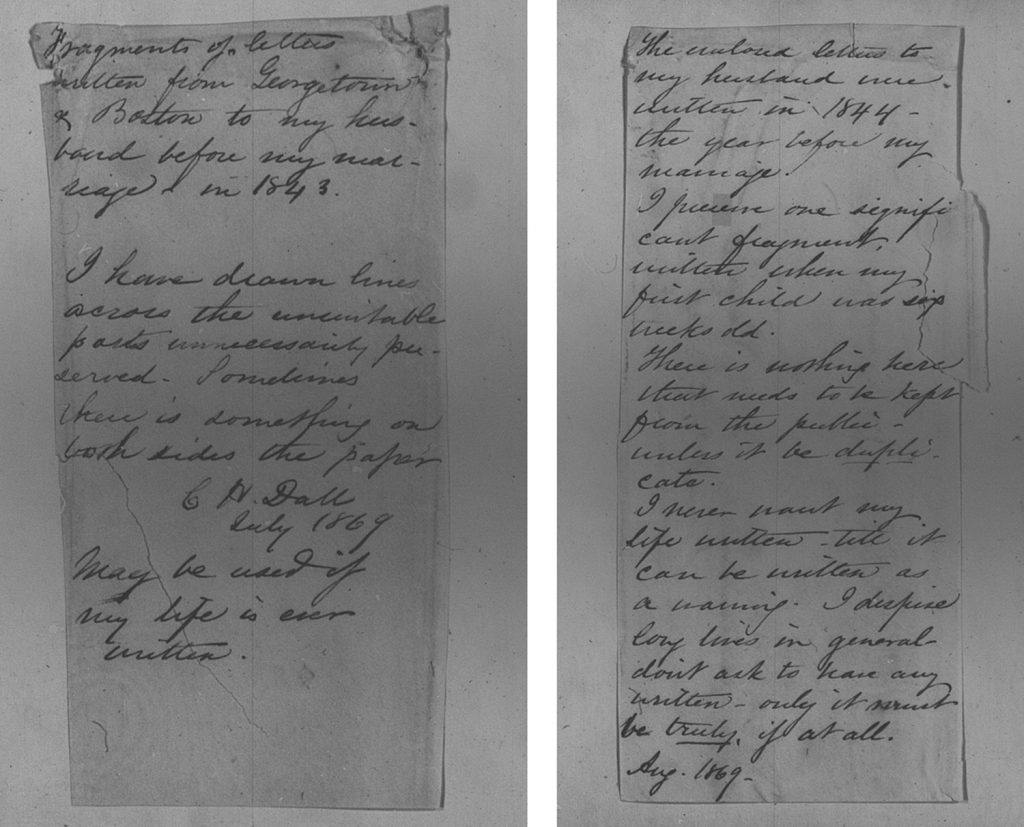

Dall’s careful curation of her personal papers reflects her belief in the historical significance of her activism. She debated writing an autobiography for decades. Referring to Julia Ward Howe’s Reminiscences as evidence of “self-conceit,” she was wary of the potential ramifications of revealing her innermost thoughts.[v] Many of her annotations control the narrative of her life. Dall ripped, destroyed, and crossed out material she deemed “uncharitable parts unnecessarily preserved” but once added to the remainder “may it be used if my life is ever written.”[vi] In July of 1869, she indicated that she had censored a collection of letters from 1843-1844 concerning her marriage. Later, she wrote, “I never want my life written – till it can be written as a warning. I despise long lives in general – don’t ask to have any written – only it must be, truly, if at all.”[vii] Dall believed a biography would be written with or without her consent. The proactive decision to send her papers to Boston herself, rather than trust an executor, illustrates how she inserted herself into the archival process.

Annotations offer insights into Dall’s changing relationships with contemporaries like Ednah Dow Cheney, Paulina Wright Davis, and Theodore Parker. Dall and Cheney met in their childhood years, but by 1878, experienced a rift in their friendship. “No act of mine is the cause of Mrs. Cheney’s late demeanor to me. I am told it is caused by envy & jealousy,” Dall scribbled on the back of a letter from Cheney she ultimately discarded, “Alas! what does she envy?”[viii] On a letter from Davis, she admitted that its contents were “discreditable to Mrs. D” but advocated for its preservation regardless. Dall also marked letters to and from Parker with the date ‘May 28, 1898,’ suggesting her intention to organize, review, or publish her exchanges with the radical abolitionist and lecturer. Her annotations reveal her perspective of the era and serve as guidelines for future biographers. She identified letters of “an historic bearing and interest” and remarked on feminist and reform concerns.[ix] On December 5, 1899, days before she sealed the final trunk bound for Boston, Dall penned, “The letters enclosed throw light on my own life from 1849 to 1869 during many dark & doubtful days, when I stood alone as few women ever do … No one may ever care to read them – but they show how groundless many women have been & I think best to preserve them.”[x]

Historians of the nineteenth century rarely get the opportunity to commune directly with their subjects. The annotations within Caroline Dall’s papers offer a glimpse into what she herself viewed to be the pivotal achievements, tragedies, and challenges of her life. Her commentary transforms her writings into multidimensional documents transcending decades and reflecting both her immediate reactions and retrospective reflections. Furthermore, they create an immortal dialogue with the imagined reader. In this way they are living documents, offering both tantalizing possibilities for historical discovery and stark warnings to the intrepid biographer.

[i] Caroline Dall, Journal Vol. 42, December 7, 1899, Caroline Healey Dall Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society.

[ii] Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Second Series Vol XI 1896-1897 (Boston: Published by the Society, 1897), 333; Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Second Series Vol. XIII, 1899-1900 (Boston: Published by the Society, 1900), 310; Massachusetts Historical Society Proceedings October 1909 – June 1910, Vol. XLIII (Boston: Published by the Society, 1910), 38; Massachusetts Historical Society Proceedings October 1912 – June 1913, Vol. XLVI (Boston: Published by the Society, 1913), 379. In addition to her personal papers, Dall donated a “rail cut by Abraham Lincoln” and a cabinet table.

[iii] An additional 11.5 boxes, 5 photograph folders, and 1 folio folder of Caroline Dall’s papers are held Harvard’s Schlesinger Library.

[iv] Caroline W. Healey to the Teachers of the West Parish School, September 17, 1842, Correspondence, Reel 1, CHD Papers.

[v] Caroline Dall, Journal Vol. 42, December 7, 1899, CHD Papers.

[vi] Note within letters dated July 1869, Correspondence, Reel 1, CHD Papers.

[vii] Note within letters dated August 1869, Correspondence, Reel 1, CHD Papers.

[viii] Ednah L. Cheney to Caroline H. Dall, April 13, 1856 [back page of letter, rest discarded], note dated 1876, Correspondence, Reel 2, CHD Papers.

[ix] Caroline H. Dall to Paulina W. Davis, November 1855, Correspondence, Reel 2, CHD Papers.

[x] Note within letters dated December 5, 1899, Correspondence, Reel 1, CHD Papers.