By Miriam Liebman, Adams Papers

In the period following the American Revolution, Republican Motherhood, or the civic virtue of raising good republican children to serve the new nation as engaged citizens, defined many American women’s roles in the early United States. During his presidency, John Adams received several letters from women embodying this role. While most historians of Republican Motherhood focus on the positive side to that role, the letters to John Adams highlight both a darker side and more complex understanding of this concept: mothers willing to sacrifice their children for the future of the nation.

In one such letter on 11 August 1798, Abigail Cunningham, of Lunenburg, Massachusetts, used examples from both Ancient Greece and the Bible to describe the sacrifice she would make as a mother for her beloved nation. As a mother, she raised her sons to go to the front lines explaining, “if they ware Calld to Action, in defence of their Country, to Count not their Lives Dear in Defience of Foreign influence, and Defence of their Countrys Cause.” And if they were to die fighting for the United States, she would respond like mothers in Ancient Sparta, “who suspended their Lamentations for the Loss their sons, or Husbands till thay examined their clothing, to see wheither the shot went in Behind or Before,” to learn whether they died fighting or retreating. She also proposed responding like Abraham in the Bible, “who Led his Beloved son to the Alter,” calmly and with composure.

Other women took a different approach from Abigail Cunningham. In the summer of 1798, Judith Sargent Murray, author and advocate for women’s rights, wrote to John Adams seeking a position in a government post for her nephew. For Murray, raising virtuous citizens meant actively participating in the government. In the early United States, elite women often wrote with patronage requests for their male relatives. Writing her nephew’s praises, she described him as having “attachment to regularity, good order, the laws and constitution of the United States is unequivocal.” It was also a way to have a steady career. While Murray wrote the letter with this patronage request, she left it to her husband to follow up when he planned to visit John Adams in a few days’ time. She wrote again in March 1799 to inquire further into her request for her nephew that she made the previous summer.

Some women wrote letters advocating on their own behalf and seeking a better life for themselves. For example, Adams also received a letter from Isabella McIntire seeking financial relief. She wrote, “the persuasion I have of your goodness and humanity has tempted me to apply to for a little assistance a Few Dollors will be a relief to a truely distressed Female.”

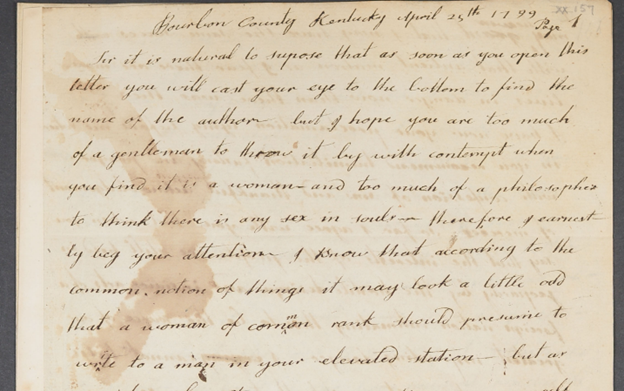

From the opposite perspective, Margaret Smith of Kentucky, a widow, writing on 25 April 1799, decried President Adams’s desire to have a standing army. For her, a standing army was the opposite of republicanism. She called on him to join with her and others for “peace and good order and pray for the anihilation of the army that is already raised and that a stop may be put to such daring encroachments on the liberties of the people.” Her husband died fighting in the American Revolution. For her, raising her children to live as good, stable citizens who could provide for themselves was her version of being a good republican mother. She explained that her greatest wish for her children was that “they live vïrtuous eat and drink and enjoy the fruit of their own labor.” In her eyes, the only reason to have a standing army was for instituting an authoritarian government. She also decried the Jay Treaty with Great Britain and believed many who fought in the American Revolution on the side of the patriots have since become corrupted. She even planned to publish this letter to John Adams in the local newspaper if she did not hear from him by 1 August. The Kentucky Gazette does not appear to have published this letter. It is possible that Smith did not go through with her threat or that John Adams responded to her letter.

Among the many letters John Adams received over the course of his presidency, these are a few from women advocating for their visions, hopes, and wants for the new United States adding to our understanding of women’s experiences in the late 18th-century United States.

The Adams Papers editorial project at the Massachusetts Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the generous support of our sponsors. Major funding of the edition is currently provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, and the Packard Humanities Institute.