By Maggie Parfitt, Visitor Services Coordinator

What are paste gems made of? Seemingly self-explanatory questions like these pop up all the time in archival research. And this one I’ll bet you haven’t given too much thought, unless you spend a lot of time thinking about historic jewelry. The answer may seem obvious, and in a sense, it is – paste gems are made of paste. (Sorry to have lied to you in the title). But there is a trick! “Paste” in this context is a certain kind of glass. I will freely admit I did not know this until a few weeks ago. I, until then, perhaps embarrassingly, perhaps understandably, thought paste stones were made of some sort of hardened glue or resin compound. (Please don’t tell my archaeology professors.)

Paste jewelry isn’t just made from any glass; the base of paste is always leaded glass, the same as antique and vintage crystal. The lead both softens the glass, allowing it to be hand cut and shaped, and makes it more refractive, so it can sparkle in aristocratic candlelight. While leaded glass has been used jewelry since at least the 1600s, Georges-Frédéric Strass, eventual Jeweler to the King of France, launched paste stones into Western fashion’s mainstream in the 1720s. 1, 2, 3

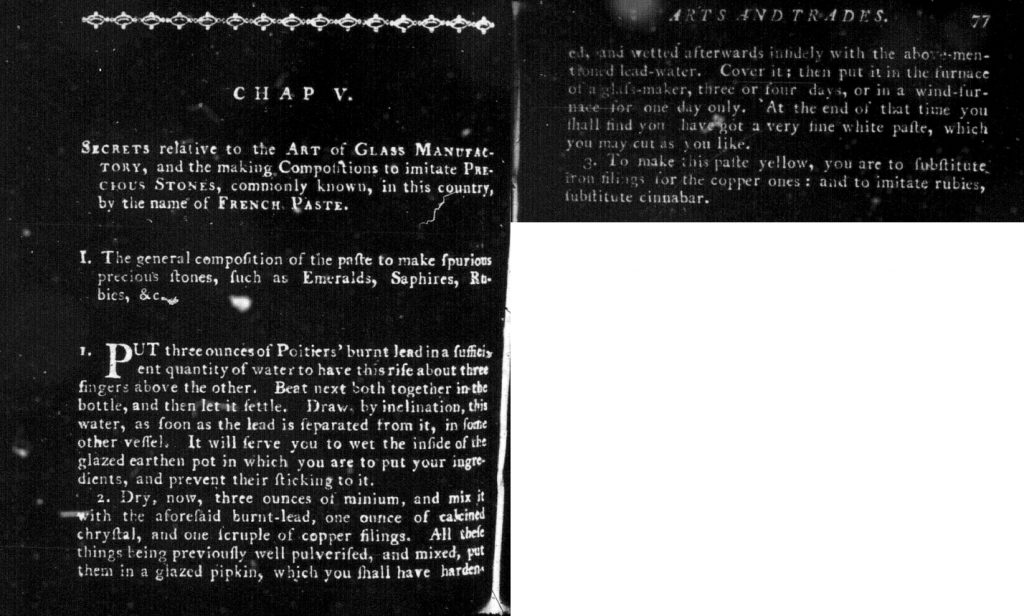

The origins of the term “paste” are debated, but the process and recipes are known. A trade book printed in Philadelphia in 17954 describes the process in roughly these steps. 1. Put three ounces of lead in water, draw out the water and use it to wet a pipkin. 2. Dry minimum and mix it with the dried lead, calcined crystal, and copper filings. Pulverize them together and put them in the pipkin lined with lead water. Cover and leave in a glass furnace for three to four days. “At the end of that time you shall find you have got a very fine white paste, which you may cut as you like.”5 The book goes on to describe recipes to imitate what must be nearly every type of gem in nearly every color. In this way paste stones absolutely allowed more creative and economic freedom to jewelry designers and makers.

There’s a modern urge to think of “imitation” jewelry purely in economic terms – of creating a cheaper product for the non-elite. While there’s certainly an economic component to glass stone production, the primary driver of their success seems to be innovation and aesthetic appeal rather than industrialization.6, 7 The King of France doesn’t need cheaper gems – but he does need novelty to impress his peers. (As much as the motivations of the aristocracy can ever be separated from their economic status.) We now think of paste stones as “imitation gems” or “false diamonds,” relegating them in our minds to the status of knock-offs for non-elite pretenders. In the 18th century these concepts weren’t mutually exclusive. One Thousand Valuable Secrets describes “how to make white sapphires to imitate true diamonds”8 and how “to counterfeit diamonds”9 but also details the rich color and beauty of these paste stones10, likening them to the highest European fashions.11

In the 18th century paste stones were cutting edge, used to experiment with the known forms of jewelry. The softness of paste allowed it to be cut and formed in a wide variety of shapes and sizes, with small, near invisible settings impossible to achieve with real gems. Uses of paste stones were varied, from elaborate necklaces to smaller items like buckles and shirt buttons.

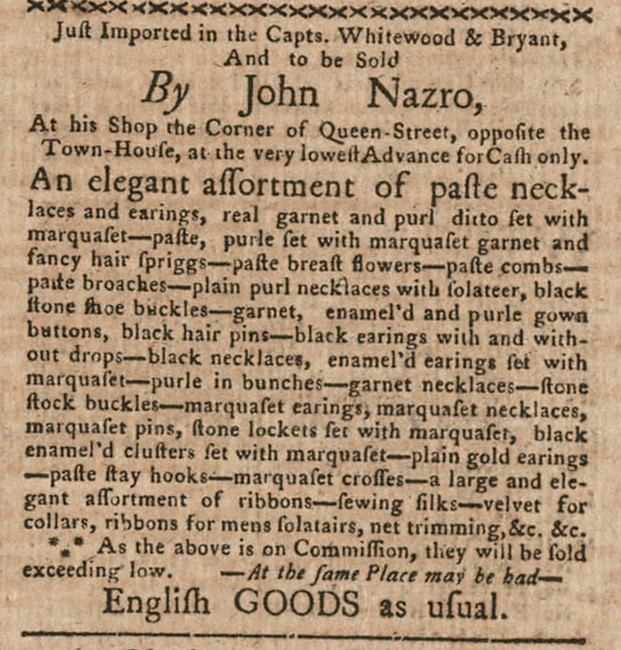

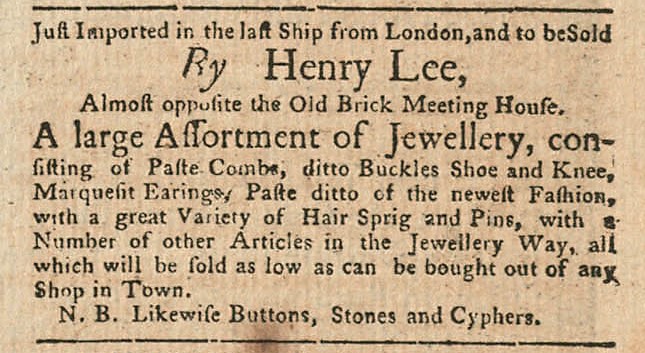

While small (this buckle is only around 3 cm square), touches like these were often considered extravagant; especially to New Englanders with Puritan roots. Finery was almost always saved for evening or state events,12 but that doesn’t mean they were unpopular or uncommon for those who had the means. Advertisements for all kinds of paste jewelry from necklaces to buckles appear frequently in 18th century Boston newspapers.

I love items like these that give us small glimpses into technology, innovation, and cultural values of given time periods. And I hope next time you encounter paste jewelry you’ll take a moment to give it its due!

- Bohm-Parr, Judith. “The Iconography of Colour: Exploring Glass as a Jewellery Medium,” 2008. James Cook University, MA thesis, (James Cook University, 2008). http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/9625. 81

- Fales, Martha Gandy. Jewelry in America, 1600-1900. ACC Distribution, 1995, 48.

- Friedman, Wendy Ilene. “Exquisite Paste | Who Needs Diamonds?” T Magazine, 21 July 2009, archive.nytimes.com/tmagazine.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/07/21/exquisite-paste-who-needs-diamonds.

- One Thousand Valuable Secrets, in the Elegant and Useful Arts: Collected From the Practice of the Best Artists, and Containing an Account of the Various Methods of Engraving on Brass, Copper and Steel. Of the Composition of Metals … And a Variety of Other Curious, Entertaining and Useful Articles. 1795. Microform. Massachusetts Historical Society, Evans Fiche: 29242, 2. 76-77

- Ibid.

- Bohm-Parr, Judith, “The Iconography of Colour,” 15.

- Friedman, Wendy Ilene.

- One Thousand Valuable Secrets, 82.

- Ibid, 91.

- Ibid, 78.

- Ibid, 87.

- Fales, Martha Gandy, Jewelry in America, 45-51.