By Russell L. Weber

You are what you eat.

Many of us have heard this common axiom at least once in our lives. For me, it was my grandmother’s constant teasing that one day I very well may transform into a “Sour Patch Kid” myself. But there is a more truthful version of this colloquialism that, if applied to historical research, unveils new avenues for the study of political gastronomy, popular culture, and identity. You bond with whom you eat.

Popular media has done an excellent job of illustrating the bonds of affection that emerge from sharing a meal – from the cacophonous, rowdy, politically charged feast held at New York City’s Life Café in Rent, to the quiet, somber dinner at The Royal Dragon, during which Matthew Murdock, Jessica Jones, Luke Cage, and Danny Rand reluctantly formed an alliance to combat an ancient, apocalyptic evil in Marvel’s The Defenders. Such bonds, however, are not limited to modern fiction.

When I arrived at the Massachusetts Historical Society in July 2018 to research the relationship between affective rhetoric and political identity in revolutionary British America, I did not expect to be struck by the meals which Massachusetts provincials consumed during the Seven Years’ War.

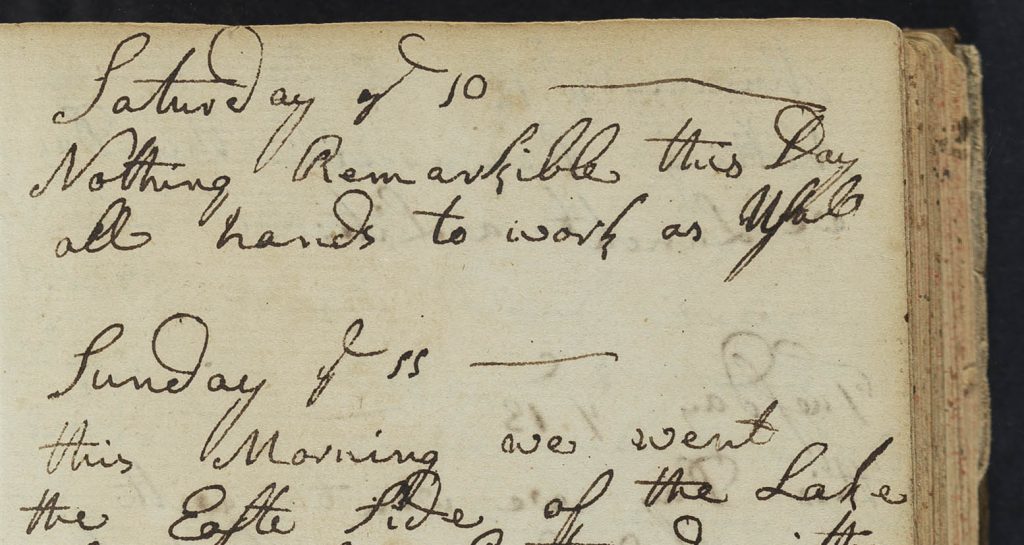

As I combed through hundreds of pages of journals and diary entries, I found a common trend. Most Massachusetts provincials greatly detailed the violence which they participated in or witnessed (be it formal combat or traumatic episodes of corporal punishment, often overseen by British regulars), but otherwise many entries – such as those recorded in Samuel Greenleaf’s journal – contained a single, repetitive phrase which described the day’s events: “Nothing Remarkable.”[1]

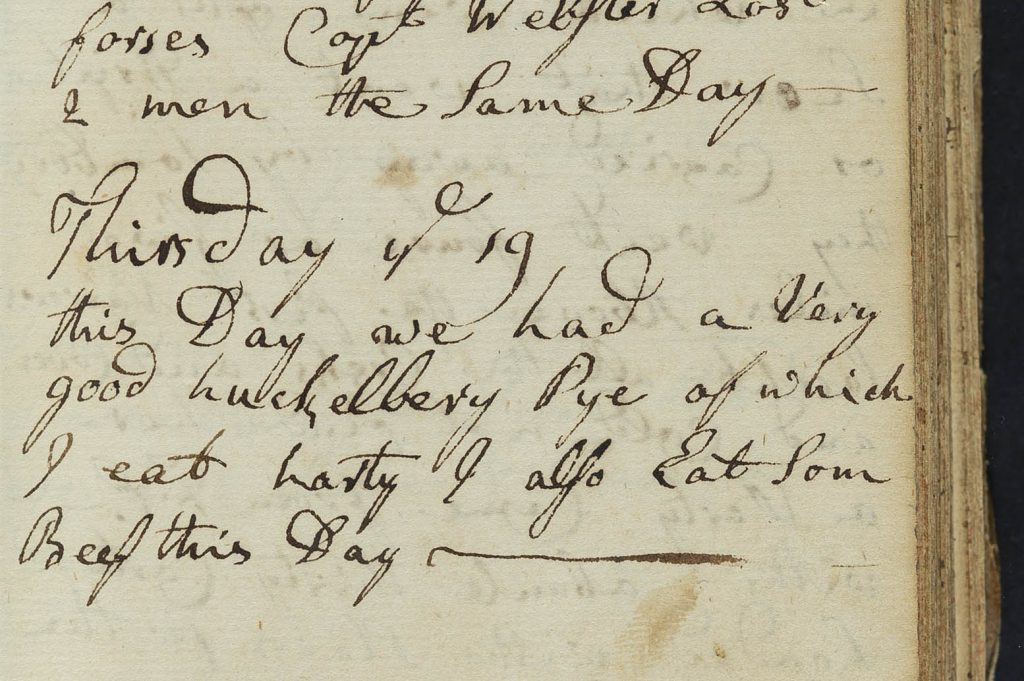

Imagine my surprise when I came across Greenleaf’s entry for August 19, 1756, when he recounted a singularly important moment for himself and his fellow provincials: “we had a Very good huckleberry Pye of which I eat harty…”[2] As a shameless fan berry pies myself, this passage struck me as a meaningful expression of acute joy. Struggling to reconcile his incessant boredom with a chronic fear of impending combat with French soldiers and their Indigenous allies, Greenleaf experienced not simply physical gratification, but rather delightful comradery by devouring such a tasty dessert with his fellow soldiers. Despite his “I” statement, it is safe to assume that Greenleaf’s fellow provincials consumed their portions of huckleberry pie with equal heartiness and conviviality. As I read further into the experiences of Massachusetts’ Seven Years’ War veterans, I became aware that such collective pleasures formed combat communities, whose members felt a sense of intimate affection as deep as, if not deeper than, their allegiance to colony or empire.

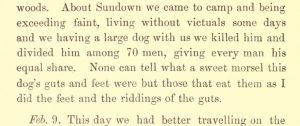

The joy that arose from feasting on fresh bread, meat, or sweet treats provides a stark contrast to one of the greatest struggles and anxieties for Massachusetts provincials: food scarcity. To avoid starvation the afternoon of February 8, 1758, Rufus Putnam and seventy other provincials reluctantly slaughtered a “large dog,” giving “every man his equal share.”[3] “None can tell what a sweet morsel this dog’s guts and feet were,” Putnam observed, “but those that eat them as I did…”[4] For only those provincials who had felt the desperation of hunger and the subsequent relief of its abatement, Putnam argued, might truly comprehend the deliciousness of such canine nourishment. Albeit a repulsive meal born from unimaginable struggle, this winter dinner only intensified the heartfelt wartime tethers of understanding, sympathy, and affection that Seven Years’ War veterans had developed for one another.

Through Putnam and Greenleaf’s journals, I realized that food – as much as rhetoric – was an essential tool to foster lasting, intimate bonds of both personal and political affection. By devouring such a “sweet morsel” – be it a dog’s feet, a slice of huckleberry pie, a plate of dumplings, or even “thirteen orders of fries” at New York City’s Life Café – strangers and friends alike had the opportunity to cultivate the affective sameness required for forging a shared political identity.

[1] Samuel Greenleaf, July 10, 1756, in “The Journal of Samuel Greenleaf,” MSS; Massachusetts Historical Society.

[2] Greenleaf, August 19, 1756, “Journal of Greenleaf.”

[3] Rufus Putnam, February 8, 1758, in Journal of Rufus Putnam: Kept in Northern New York during Four Campaigns of the Old French and Indian War, 1757-1760 (Albany: Jouel Munsell’s Sons, 1886), 56.

[4] Ibid.