By Meg Szydlik, Visitor Services Coordinator

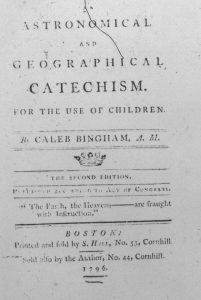

In a previous blog post I wrote about an astronomy book from the MHS collection called The Mysteries of Time and Space. I enjoyed that experience so much I decided to dig into another book to celebrate the winter solstice and clear winter skies. This time, I decided to tackle a children’s school primer called An astronomical and geographical catechism: For the use of children and selected the 2nd edition, published in 1796. I thought it would be interesting to compare it with what I learned in grade school in the early 2000s after over 2 centuries of exploration and advancement in both astronomy and geography.

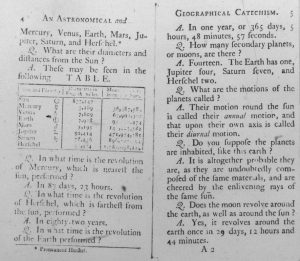

Despite being written in the 18th century, the astronomy section was shockingly similar to what I remember learning. Reading through the question-and-answer style text, I was thrown back to 4th grade, learning about stars and planets again. Precise measurements of the distance between the planets and the sun, the length of different planetary years, and even information about moons matched up with what I remember from my grade school days. The one thing that didn’t was the fact that there were 7 planets, indicating that Neptune (and Pluto) had not been discovered yet. The 7th planet, which we call Uranus today, was named but some quick googling told me that William Herschel discovered Uranus so presumably Caleb Bingham, the author of the text, just used his name. It was also so interesting to see Bingham encourage the possibility of life on the other planets in the solar system, as I was certainly taught that there was no life outside of earth. All in all, it was strikingly similar to what I learned as a child. I love knowing that while scientific discovery does grow and expand, that does not mean that all knowledge is new.

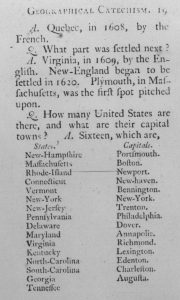

Geography, however, was a more complicated section. While there was certainly some overlap (I also learned that a peninsula is land mostly surrounded by water, for example), there were a lot of very 18th century, Early Republic aspects as well. Some of this is inevitable, since the borders of the world have changed substantially since 1796, including the introduction of 34 additional states, but some of it was a bit more surprising. When Bingham is talking about longitude, I was surprised to see no reference to the Prime Meridian which goes through Greenwich, England. It turns out that the Prime Meridian was not established until 1884, long after this book was published. Instead, Bingham says to count longitude “from a certain meridian.”

The section on continents was perhaps even more fascinating. Today of course, we consider there to be 7 continents–Africa, Antarctica, Asia, Australia, Europe, North America, and South America. However the text only offers up 2 continents: the “eastern” continent with Africa, Asia, and Europe, and the “western” of North and South America. Australia makes a surprise appearance as “New-Holland” and a potential 3rd continent. And Australia is not the only place with a new name. There are references to Prussia and Persia, neither of which exist in the same form today. It was also really startling to realize that so many states in the U.S. moved their capitals at one point or another. While the capital of Massachusetts has always been Boston, 8/15 of the states had different capitals in 1796 than they do now. There was also an extreme bias in the descriptions of the states. There was a clear preference for the Northern states over the Southern, New England over other Northern states, and Massachusetts over other states in New England. No wonder we have multiple copies of this book here at the Massachusetts Historical Society! I loved the opportunity to take a peek into what students were learning over 200 years before I entered the classroom myself. So much was the same and even the things that were different were interesting windows into 18th century exploration.

The Mysteries of Time and Space

An astronomical and geographical catechism: For the use of children