By Benjamin E. Park, Sam Houston State University

It was in the Spring of 1855 when James Patterson happened to unknowingly encounter one of America’s most prominent celebrities. Patterson, a Brown University student who was headed home to Ohio, boarded a train at Worcester and sat next to a man with a broad build and grey hair, deep in thought. The fellow passenger was furiously flipping through a large book while taking copious notes on its back page. When he completed the volume, the man took paper out of his carpet bag and maniacally scribbled for over an hour. Patterson had never seen such studious devotion on a train. Eventually, the two struck up a conversation, and the student was surprised by the man’s “gentle voice” and “kindly manner.”

Patterson was so caught up in the invaluable advice that the older man dispensed—advice that would shape Patterson’s life—that he forgot to even ask his name. It was not until later that he discovered the random seatmate was Theodore Parker, Boston’s foremost abolitionist minister during the era.

The starstruck student wrote Parker a letter, bearing his soul and narrating his own conversion to liberal religion. To his surprise, Parker responded. They then corresponded several more times over the next few years.

That Parker would exchange letters with a stranger was not uncommon. He once complained that he spent up to six hours a day responding to people across the globe, with notes from Ohio to Calcutta. But the complaint was a lie: he cherished the connections, relished the friendships, and was addicted to the art of letter-writing.

Shortly after Parker’s death in 1860, his wife, Lydia, became determined to enshrine this part of his legacy. She and an assigned biographer, David Weiss, went through Theodore’s correspondence collection and wrote nearly everyone they could to ask for Parker’s letters. Many, like Patterson, eagerly responded. “I shall never forget that lovely, gentle, kind and therefore noble, white haired man,” he wrote, as the minister had “completely won my heart.” Patterson had even become a minister, just like his idol. He sent Lydia the only two remaining letters he could find—so long as she promised to send them back once she had copied their contents, so that he could keep them as relics.

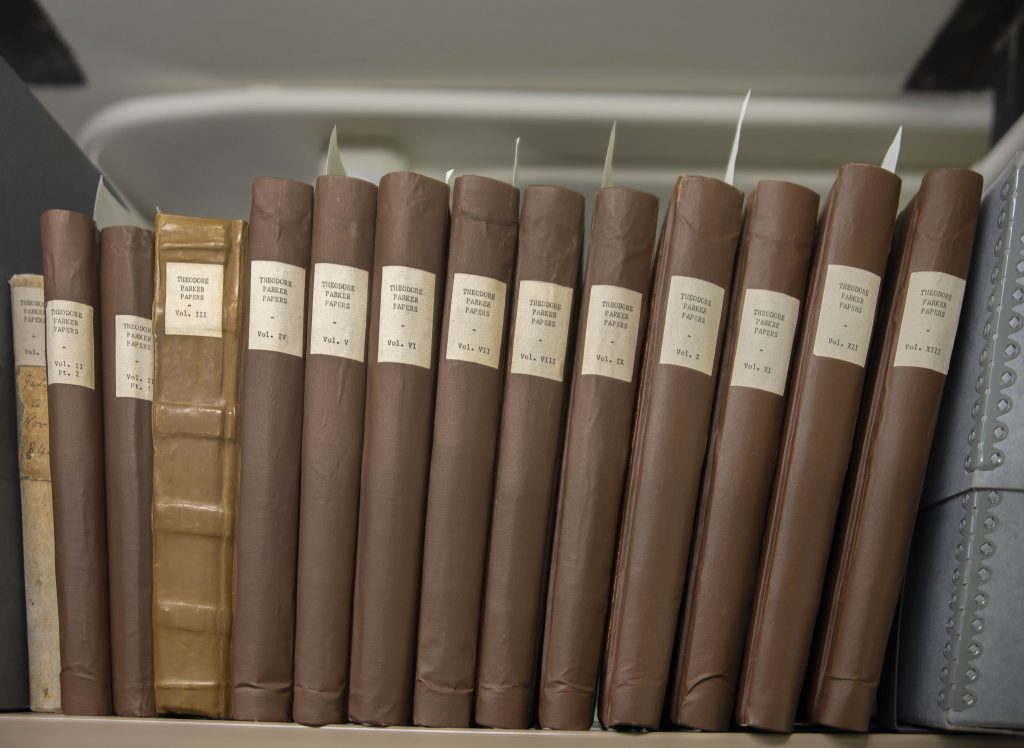

Lydia Parker and David Weiss eventually collected enough incoming and outgoing correspondence to fill thirteen large volumes, all but two of which are housed at the Massachusetts Historical Society. (The other two are held in the Harvard Divinity School archives.) Each volume, numbering between four hundred and eight hundred pages, features transcriptions of hundreds of letters. Interlocutors include Theodore Parker’s Harvard classmates, rival ministers, adoring followers, and devoted critics. He received letters from worshipful fans who wrote him about how his writings prompted their own spiritual or moral awakening; these converts to “Parkerism” ranged from an itinerant minister in upstate New York to Queen Victoria’s dressmaker in Buckingham Palace.

But perhaps the most revealing exchanges found in these packed volumes concern the intersections of religion, abolitionism, and politics during the decade that America fractured into two. Though a minister, Parker became a prominent leader in the antislavery movement and corresponded with many of the central players in the new Republican Party. William Seward told Parker that he had done more in “the awakening of the spirit of Freedom in the Free States” than anyone else, and plotted with him on how best to oppose the “Slave Power.” Charles Sumner strategized with Parker, his favorite minister, on how to consolidate opposition against the Democrats, and even wrote him mere days before his caning in 1856. William Herndon sent Parker weekly dispatches from the Lincoln/Douglas debates in Springfield. And John Brown coordinated with Parker concerning his attempted raid on Harper’s Ferry.

The Theodore Parker letter books are among the most important manuscript collections to understand the key issues that animated America during the mid-nineteenth century. They are among the most prized gems in Massachusetts Historical Society’s archives, and a testament to how documents can reveal the potency of the past to the present.

Benjamin E. Park is author of American Nationalisms: Imagining Union in the Age of Revolutions, 1783-1833 (Cambridge University Press) and Kingdom of Nauvoo: The Rise and Fall of a Religious Empire on the American Frontier (Liveright). His next book, American Zion: A New History of Mormonism (Liveright), will appear in January 2024. He is currently working on a new project examining religion and the abolitionist movement, which was benefitted by an MHS research fellowship.