By Michael Larmann, Doctoral Candidate, University of Montana

The past several years have sparked public debate on monuments and how they tell about our national story. Much of this debate has targeted southern confederate monuments following the American Civil War. While this debate might seem recent, Americans have been fighting over controversial monuments for a long time.

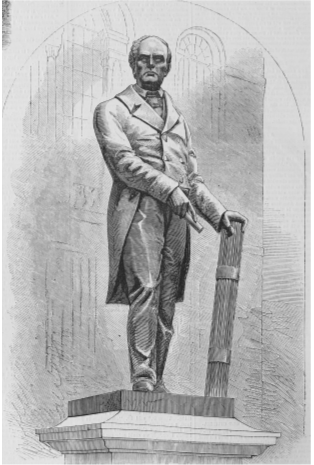

There is a monument in Boston, now largely forgotten, that divided the commonwealth before the Civil War. This bronze statue guards the front of the Massachusetts State House on Beacon Avenue. To the right of the main stairs, antebellum statesman Daniel Webster stands on a granite pedestal. In his right hand, the “Great Expounder” grasps a scroll, likely the U.S. Constitution that he swore to uphold during his long career as a congressman and Sectary of State. His left-hand rests upon bound fasces representing the Union he defended. I traveled to the Massachusetts Historical Society because I wanted to learn how this monument became a symbol of political strife during the Civil War era.

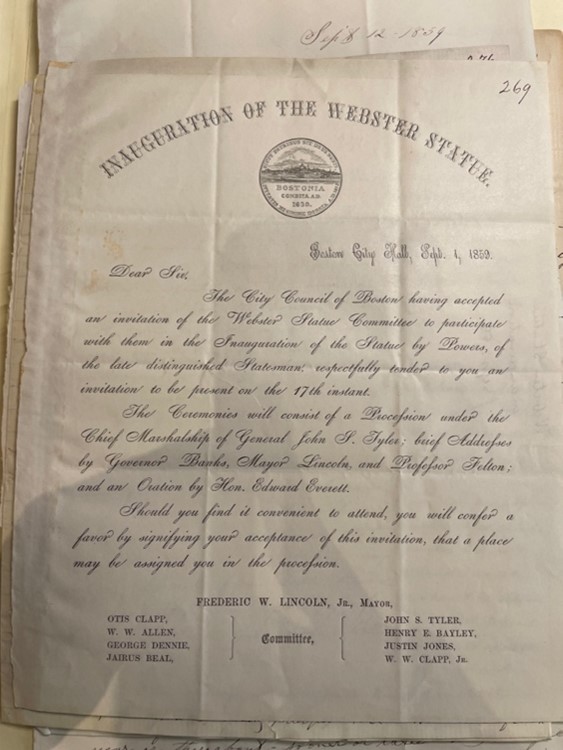

As indicated by this invitation issued to textile manufacturer Amos A. Lawrence, Boston was going to inaugurate Webster’s statue with a grand procession outside the State House on September 17, 1859. However, a Northeastern storm forced celebrations inside the nearby Boston Music Hall. The commonwealth re-inaugurated the statue on September 27th before a crowd of ten thousand people. Republican Governor Nathaniel P. Banks and Whig orator Edward Everett delivered speeches on Webster’s distinguished career.

Not everyone in attendance, however, agreed that Webster was worthy of public commemoration. While Everett spoke, local abolitionists circulated petitions through the crowd to secure the statue’s removal. William Lloyd Garrison, Wendell Phillips, Lydia Maria Childs, and many others protested Webster’s late support for the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. A Webster monument, they contended, bestowed “no honor to the state” and was “repugnant to the moral sense of the people.”[1]

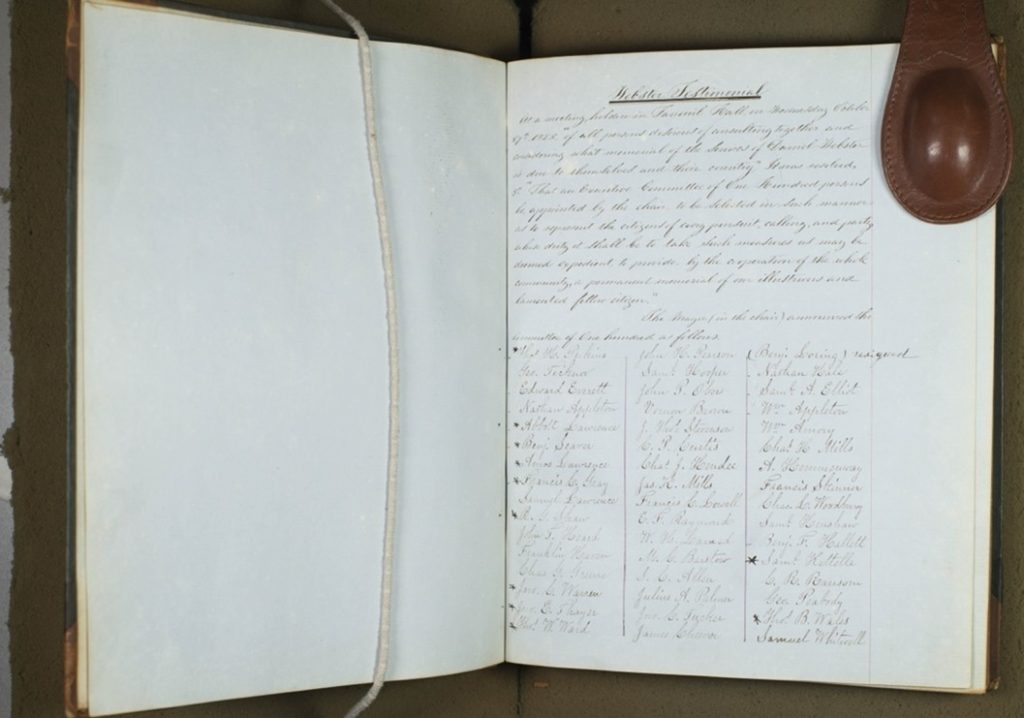

According to abolitionists, the Webster monument represented the Cotton Whigs and commercial elites on State Street, who relied on slave-produced commodities. The Webster Memorial Committee included the most affluent and influential men in antebellum Massachusetts. George Ticknor Curtis, the judge who enforced the Fugitive Slave Law against Thomas Sims in 1851, was the committee secretary. He submitted this bound volume of the committee’s records to the MHS which listed the one hundred members and their activities.

Committee members also included conservative politicians such as Edward Everett, textile manufacturers including Nathan Appleton, and banking agents such as Thomas W. Ward. After looking through these individuals’ papers at the MHS, it became clear that the elite’s commemoration of Webster aligned with their conservative politics and economic dependence on slavery. Many of the committee members publicly supported Webster’s “Seventh of March” Speech in 1850 because they saw the Union as essential to their political views and economic interests.

With growing anti-slavery sentiments in the 1850s, it may seem surprising that the Webster’s statue remains standing in 2023. John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry on October 16, 1859, southern secession, and the coming of the Civil War pushed the Webster monument far from the public mind.

Today, security precautions prevent the public from viewing Webster’s statue up close, but we can still learn a great deal from it as a historical source. The monument demonstrates that Americans have been engaging in the politics of commemoration long before us. While controversial statues have become a hot topic, this discussion predates our contemporary political situation. In addition to southern monuments of enslavers and confederate soldiers, there are also problematic statues in the North of individuals like Daniel Webster who made controversial compromises over slavery.

Adding even greater complexity, the Webster Memorial Committee possessed their own political, legal, and economic ties to slavery. The politics of commemoration was not solely about the final product, but also the process of erecting the monument itself. People understood these monuments as reflections of their communities’ values, which often led to conflict. When viewed as historical sources, these statues can reveal the contentious nature of American democracy both past and present.

[1] “The Inauguration of the Webster Statue,” Liberator (Boston, MA), Sep. 16, 1859.