By Meg Szydlik, Visitor Services Coordinator

Content warning: use of outdated but period-typical language to describe disabled individuals.

With this post, I am returning to my old stomping ground in the archives. I have written three previous blog posts focusing on the presence of disability in our archives which can be found here, here, and here. I wanted to dive into some more collection materials on the topic.

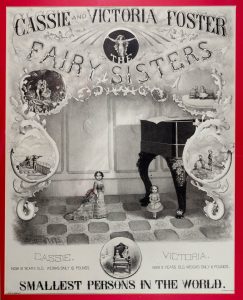

While looking at our online collections, I came across this poster advertising the “Fairy Sisters” in 1873. The two girls, named Cassie and Victoria Foster, were little people and were billed as the smallest people alive. Whether or not that was true, that was their claim to fame, and later that of their brother, Dudley. Both of the girls died tragically young of infections Victoria at 3 ½ and Cassie at 11. Dudley lived to 17 before dying of a heart condition. Their lives, and the way some people still talk about these performers, demonstrate the tendency of others to romanticize the exploitation these children experienced. Personally, I’m not convinced that a 3 ½ year old should be working in any capacity and I’m even less convinced when the work consists of being gawked at by strangers for their disability. However, it would be many years after all three of these children’s deaths that legislators would even sign the Coogan Act, a law intended to protect child performers.

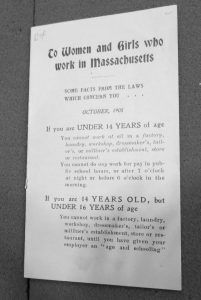

The 19th and 20th centuries were full of labor strikes and gains, including laws limiting and prohibiting child labor. The 1908 pamphlet shown below outlines some of the restrictions for girls and women in the workforce, including hour restrictions, school requirements, and access to workers comp if injured on the job. Their lives were certainly not easy, but there were at least some protections. Others took up the fight against child labor as part of the general battle for labor rights. It’s hard to read about all the child labor fights and not think about how different the lives of child performers would have been had they been afforded the same opportunities, limited as they were for the impoverished mill worker children these pamphlets were given to. In fact, the entertainment industry is still exempt from a lot of the same child labor laws that govern virtually every other industry and it shows in the current boom of podcasts from grown-up child stars

Both the mill children and child circus performers lived brutal lives, but there was little romanticization of mill workers’ lives. In contrast, there was (and still is) a romanticization of circus and sideshow life. The lights! The glamour! Life on the road! They were loved by millions! What could they possibly have to complain about? That perspective fails to account for the rampant abuse in the industry. Being on display is not something many people are comfortable with, especially when they are not demonstrating a skill. A gymnastics showcase is a bit different than staring at someone because something about their body is non-normative and usually specifically disabled, whether it is microcephaly, dwarfism, or giantism. The objectification is made even worse by how young some of the people in the sideshow were.

Eventually laws were signed to protect disabled children including the 1975 Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Regardless, the Fairy Sisters and their brother should never have been sideshows as children. They should have been children and children only.