By Gwen Fries, Adams Papers

In 1842, just shy of his thirtieth birthday, Charles Dickens undertook his first tour of America. He and his wife, Catherine, arrived in Boston in January. “I can give you no conception of my welcome here,” Dickens wrote on 31 January. “There never was a King or Emperor upon the Earth, so cheered, and followed by crowds, and entertained in Public at splendid balls and dinners, and waited on by public bodies and deputations of all kinds. . . . If I go out in a carriage, the crowd surround it and escort me home.”

Charles Francis Adams, son of John Quincy and Louisa Catherine Adams, concurred with Dickens’s summary, writing from Boston to his mother in D.C., “Society here is in a state of ferment at the appearance of Mr Dickens the celebrated Boz. He is lionized at a rate beyond the imagination of a moderate man to conceive.” Though his wife and children were ardent fans, Charles admitted, “I did not know before that Mr Dickens was so great a man but that is my fault in not keeping pace with the age.” He teasingly warned his parents to brace for impact because the whirlwind of Dickens was headed to Washington. (John Quincy seemed to do just that, cramming in a last-minute reading of The Pickwick Papers.)

Dickens stopped at New York City on his way south, where he made the acquaintance of prominent businessman (and host of the Knickerbocker group) Charles Augustus Davis. Davis enjoyed a twenty-year acquaintanceship with John Quincy Adams, and, at Dickens’s urging, he immediately set about laying the groundwork for an introduction.

Davis sent a flurry of letters to the Adams home pleading Dickens’s case: “I have seen much of him & I am charm’d with him— he is as delicate minded & pure in spirit as a Young Girl— I want him to know you & I will Esteem it a favor if you will allow me to give him a Letter to you— he will be most happy to make your personal acquaintance.” When this received no reply, he sent another, “He will take great pleasure in making your personal acquaintance and I am quite sure that you will find this pleasure mutual. for my own part I can only say that my intercourse with him is mark’d down as among the brightest & most agreable moments of my life.”

After Davis’s third imploring letter, Louisa responded that they should be glad to host Mr. Dickens and his lady.

On 10 March, his first morning in the capital, Dickens made it his mission to meet Adams. In his diary that night, Adams recorded, “Mr Charles Dickens and his wife called and left cards, and a Letter of introduction from Mr Charles A. Davis of New-York.” When Dickens found Adams was not home, he followed him to the House. “Mr Nathaniel Tallmadge one of the Senators from New-York, came into the house with Charles Dickens and called me out from my seat and introduced him to me.” The 30-year-old Dickens viewed 74-year-old Adams with a deep reverence—particularly for his abolitionist activities. In his Travels in America, Dickens not-so-subtly alludes to “An aged, grey-haired man, a lasting honour to the land that gave him birth, who has done good service to his country, as his forefathers did, and who will be remembered scores upon scores of years after the worms bred in its corruption are but so many grains of dust.”

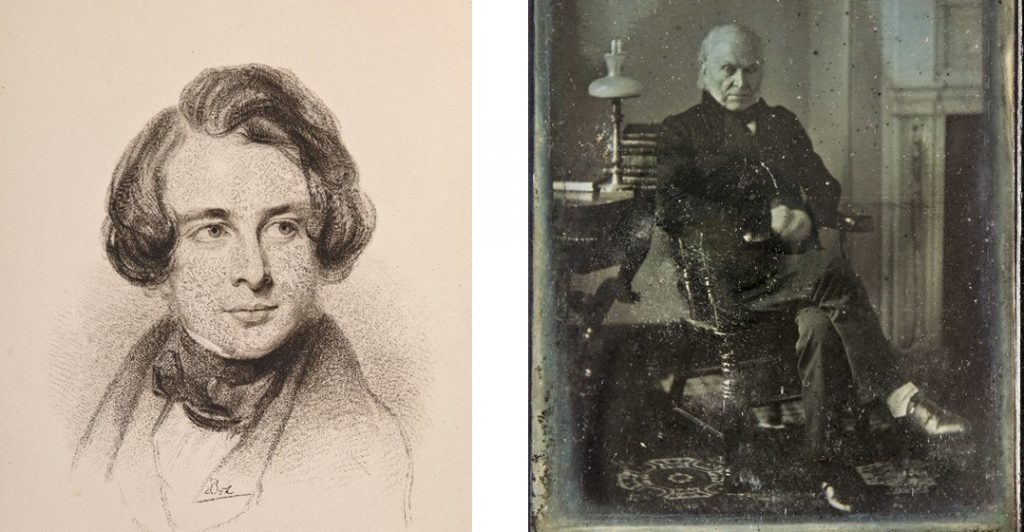

Right: John Quincy Adams, Philip Haas, 1843 (National Portrait Gallery)

Louisa wrote to her daughter-in-law Abigail Brooks Adams to describe what happened next. Louisa invited the Dickenses “to take a seat in our Pew at Church and afterwards to dine with us sociably at 1/2 past 2. The invitation was declined; and I thought that I should see nothing more of the literary Monster. The day after; a Note was brought to me stating, that Mr. & Mrs. Dickens being very sorry that they were engaged out to dine; if it was agreeable to me they would come and take a Lunch at my Dinner, and thus have the honour to pay their respects to the family of Mr. Adams.”

John Quincy noted in his diary that, “They are so beset with civilities, and kind attentions, that they have not a moment of time to spare, and it was only by snatching an hour from other engagements that they could see us at all— Dickens’s fame has been acquired, by sundry novels and popular tales . . . more universally read perhaps than any other writer who ever put pen to paper— He came out in the January steamer to Boston, and his reception has transcended that of La-Fayette in 1824.”

The dinner was a success. Louisa wrote, “We had as pleasant an off hand dinner as you can well imagine— Dickens is an unpresuming lively and agreeable man, and seemed perfectly delighted with the coversation of his Host; and by the time they left us . . . you would have supposed we had been long acquainted.”

Dickens was equally impressed. To a friend in England, he wrote, “Adams is a fine old fellow—seventy-six years old, but with most surprising vigour, memory, readiness, and pluck.”

On their way out of the city, Charles and Catherine Dickens stopped to bid farewell to the Adamses. Catherine even asked John Quincy if he would write a poem for her, which he gladly did:

There is a greeting of the heart

Which words cannot reveal—

How, Lady, shall I then impart

The Sentiment I feel?How, in one word combine the spell

Of joy and sorrow too;

And mark the bosom’s mingled swell

Of welcome!—and Adieu!

The Adams Papers editorial project at the Massachusetts Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the generous support of our sponsors. Major funding is provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, and the Packard Humanities Institute. The Florence Gould Foundation and a number of private donors also contribute critical support. All Adams Papers volumes are published by Harvard University Press.