By Meg Szydlik, Visitor Services Coordinator

As Halloween approaches and the air becomes colder, I find my mind turning to all things spooky and supernatural, including witches. Witches in Massachusetts have a long and storied history, though up until recently it was not a happy one. While Salem, for example, is home to a lot of self-proclaimed witches nowadays, the 1690s witch-related history is pretty ugly. You can learn more about the connections between the MHS and the Salem Witch Trials in this podcast.

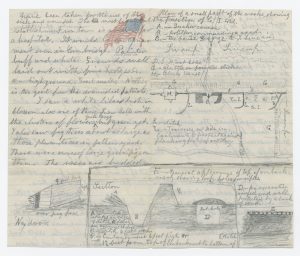

While the Salem Witch Trials are an especially famous example of New England’s hostility towards those suspected of consorting with the devil, witch hunts were not unique to the region. In fact, Europeans were having witch trials back in the medieval period. They brought those ideas and fears with them across the Atlantic along with physical copies of books they used to help identify and prosecute witches. Books with titles so long they are not fully written out in our catalogue like A collection of modern relations of matter of fact, concerning witches & witchcraft upon the persons of people… and The infallible trve and assvred vvitch haunt the stacks. I took a look at one specific book called A compleat history of magick, sorcery, and witchcraft… and learned a lot about these supposed witches.

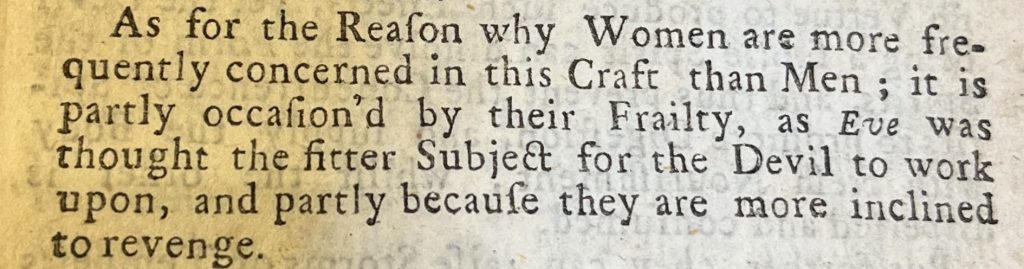

According to A compleat history, women are far more likely to be witches because they are more frail than men, but also “partly because they are more inclined to revenge (15).” I confess that while I expected the frailty argument, much as I disagree with it, the revenge argument startled me a bit! While many stories portray witches as vengeful, I had never heard the reasoning that women are inherently more revenge driven. Truthfully, given the way women are treated, if revenge was the reason women become witches, I’m surprised there weren’t more!

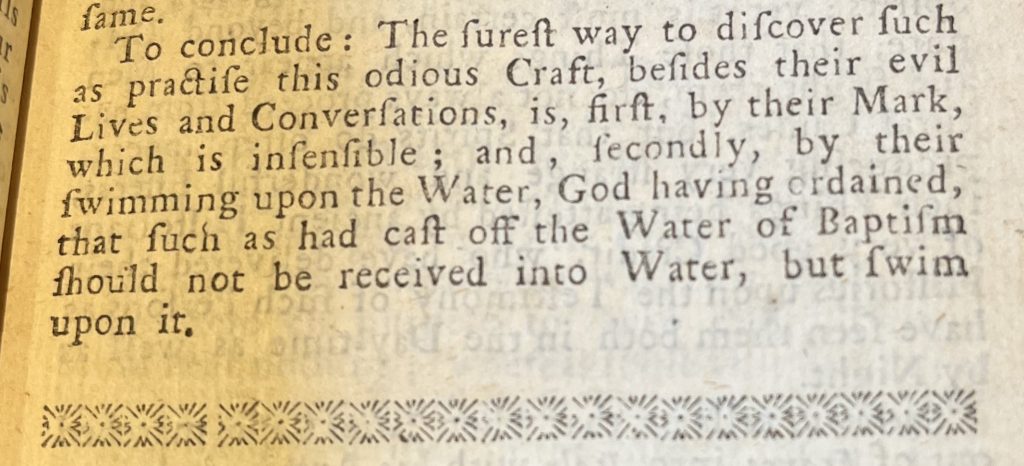

While women were most commonly accused of being witches, men could be as well. In the Salem Witch Trials, for example, 5 men were hanged for witchcraft along with 14 women. A compleat history provides modern, rock-solid methods to prove that someone is a witch: find their Mark (where the devil allegedly marked those who served him) or see if they float in water since “God having ordained, that such as had cast off the Water of Baptism should not be received into Water, but swim upon it (23).” Different books advise different things, of course, and every trial has their own specific rules. There is a clear desire in this guidebook to demonstrate that the witches in their case studies are causing actual harm and “fits” through the spirit realm. Reading it with modern eyes, I can see how it would be persuasive in a world where these types of beliefs were normal and there were no other clear explanations for the behaviors.

Witchcraft is such a fascinating subject because it taps into a view of reality that we simply do not have today in 2023. As a society, we do not believe that people can encounter the devil and do supernatural harm that can be pursued in court. While things like spirits and vampires are definitely still common in pop culture, they are not part of the legal understanding of the world. A huge shift from a world in which respected community leaders decided if spectral evidence was admissible in court. Today, witches still exist, but they are no longer seen as people who have relations with the devil. Instead, Wicca and other religious traditions embrace the title “witch” with a very different spin, one where they are hopefully not the target of state-sanctioned violence.