By Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

This is the seventh installment in a series. Click here to read Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V, and Part VI.

This post contains descriptions of graphic violence.

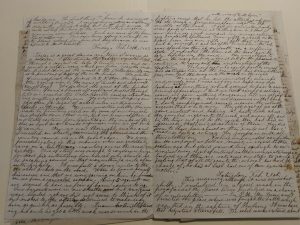

In this series about the Civil War journal of Howard J. Ford, I’ve argued that Howard’s journal paints a particularly vivid picture of the war. His use of sensory details makes it feel like you’re right there with him. Today I’d like to focus exclusively on his entry for 20 February 1863, an entry that begins: “Today is a great day in my term of service as a soldier.” In it, Howard describes a chilling encounter with an unnamed Confederate soldier that illustrates, in stark terms, the brutality of war.

When we left off a few weeks ago, Howard’s company (Company I of the 43rd Massachusetts Infantry Regiment) was enjoying some quiet days of picket duty at Evans’ Mill, not far from New Bern, North Carolina. Then Howard was selected to go on a scouting mission.

After dinner the Captain requested Odell through a sargent [sic] to take 4 trusty men and examine a certain road […] He selected of course, first, his friend H.J.F. then Mr. Snow and then 2 young men by the name of Brooks and Ashworth. (Lowell boys.)

The scouting group consisted of Cpl. James K. Odell; Harold himself (H.J.F.); Pvt. Russell L. Snow, who we met in Part VI; Pvt. Sager Brooks, an immigrant from England; and the youngest of the five, 19-year-old Pvt. Charles Ashworth.

We entered the road at the picket station, found a blocade [sic] all right, and pushed through till we reached the Pollocksville road without seeing anything suspicious. We were now keeping our eyes open for “signs” of rebels when we discovered tracks in the road. […] Now we were thoroughly awake and proceeded on slowly, examining the ground and the country round us with great care.

It wasn’t long before things went sideways.

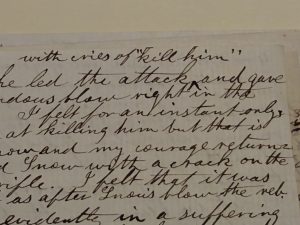

We suddenly came on a Southerner crawling across the road on his belly. […] When he found himself discovered and that we were gaining on him he fired on us from a concealed weapon. Being 5 against one we seemed to have no fear of harm coming to us. Our bayonets were in our sheathes but our guns were loaded yet we did not seem to think of it but rushed to the attack determined to make way him as quickly as possible. Snow […] led the attack with cries of “kill him” and gave the old sneak a tremendous blow right in the middle of the back. I felt for an instant only some pangs of conscience at killing him but that is our business just now and my courage returning I instantly followed Snow with a crack on the head from my own rifle. I felt that it was but a merciful act as after Snow’s blow the reb was speechless though evidently in a suffering state. I repeated the blow on the head and he lay lifeless in the road.

Keep in mind, Howard was sending this journal home to his family in installments. In my experience, this kind of explicit account was rare for the time. Most soldiers shielded their families from the gruesome details—or avoided discussing them for reasons of their own mental health. Howard continued,

We were obliged to leave the mangled body where it fell for the present & continue to carry out the instructions of the Captain. The corporal who could hardly conceal his satisfaction at the result of his scout thus far, now led the way into the woods on the right.

Interestingly, Howard returned to the subject the next day.

I hope my relatives will not be alarmed at the dangerous position they may think we got into the other day. I hope you will approve the manner in which we killed the snake.

Howard volunteered for several more scouting trips in the days following this “great” and “exciting” event. On 1 March 1863, his company returned to Camp Rogers at New Bern. Stay tuned to the Beehive for more of Howard’s story.