By Susanna Sigler, Processing Assistant

I’ll be the first to confess it: I’m a notebook fiend.

It started innocently enough. Now, the collection I’ve amassed (and several times purged) should be enough to sustain me through at least ten Great American Novels. If only, of course, I actually wrote in any of these books for more than a few months at a time. As the child of a self-proclaimed Moleskine addict and a collector (and actual filler) of sketchbooks, I had no chance.

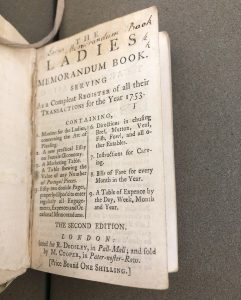

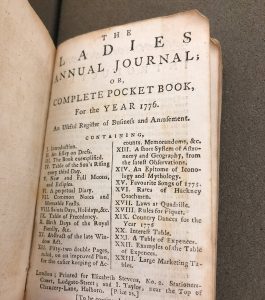

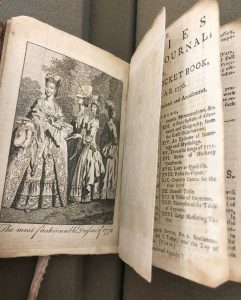

This is all to say that when I came across a set of 18th century ladies’ memorandum books in the Price-Osgood-Valentine papers, I was delighted and intrigued.

Printed in England and marketed towards upper-class women as a sort of daily planner, these books offered space to keep track of dates and household expenses as well as advice on topics such as marriage, managing staff (servants), parenting, and fashion.

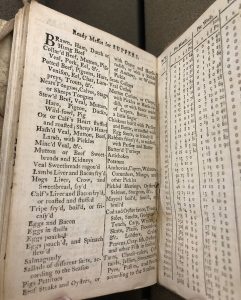

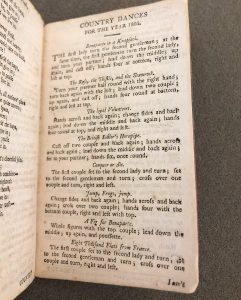

Additional sections vary from book to book; one might include the line of succession to the English crown and currency tables, another the steps to popular dances and the songs that accompany them. My personal favorite is a section on monthly meal planning with a page of dinner ideas–“tripe fry’d,” anyone? In collections services at the MHS, we also found hilarious a section of riddles for which the reader had to wait until next year’s edition to find out the answers.

These planners offer a glimpse into the lives of the women who bought and used them, what was expected of them by English society at large, how they were being told to live their lives and with what responsibilities of person and home.

One essay, printed at the beginning of one of these books, is titled “Maxims for the LADIES concerning The ART of PLEASING.”

A few select quotes (I have taken the liberty of changing the 18th century f’s to s’s):

“It seems as if the Author of Nature, by giving Beauty of Person, and Softness of Manners to the Female Sex, intended their principal Business should be to please.”

“Modesty, is a young Maiden, is Sensibility check’d by Delicacy. It is the first and most pleasing Virtue of a Woman, as it is a proof her heart is capable of Love, and a Presumption that it will continue pure and uncorrupted. She who has no Sensibility, can have no Modesty.

“Cultivate in your Breast the Virtues of Mildness and Good-nature; for depend upon it, there is no Fiend that a Man would not sooner choose to be tormented with, than with that hideous Creature call’d a Woman of Spirit. A Woman of Spirit is a fallen Angel chang’d into a fury.”

I will resist the urge to get the last one printed on a t-shirt.

Most strikingly, aside from their language, these essays are almost exactly identical to newspaper articles I’ve read from the 1930s through the 1950s as well as women’s magazines through the mid-aughts, and, dare I say, the social media of today – the “divine feminine” of certain slices of the so-called wellness industry, and the “girl dinners” of TikTok.

The next essay, “Maxims for Wives,” takes on more of a knowing tone, like it’s being written with a wink. “Art thou marry’d?” it asks. “Alas poor Woman, thou hast parted with thy Liberty!” However, it does not stray from its main message. “[T]here are Ways and Means to make this Lord of thine the kindest and most agreeable Friend thou could’st have had.” It ends with the following advice: “Observe the Temper of your Husband: conform to it when it is good, and calmly submit where you think it otherwise, and you will have learnt the hardest Lesson in the Art of Pleasing.”

Physically, the books were once beautiful objects–they still are, although the leather is now worn and the ribbons frayed. It made me yearn for an updated version: a pocket-sized planner with good paper and a nice cover, with space for notes as well as helpful information. For instance, train timetables readily at hand (though maybe we could have a reliable train schedule to start), some book or movie recommendations, or essays on how not to abandon a journal two weeks into starting it. The most comforting aspect of these books, I’ve found, is that none of them have been completely filled.

The books can be viewed here at the MHS as part of the Price-Osgood-Valentine papers.