By Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

This is the sixth installment in a series. Click here to read Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, and Part V.

We return to the story of Pvt. Howard J. Ford of the 43rd Massachusetts Infantry, as told in his Civil War journal at the MHS.

On 21 December 1862, after ten days of hard fighting and marching in the Goldsboro Expedition, the 43rd Regiment returned to New Bern, North Carolina, just in time for Christmas. What followed was a period of relative quiet for Howard. Instead of writing about bullets whizzing over his head, he was free to write about—what else?—food! For example, on Christmas day, Howard had a dinner of hard tack, salt beef, sweet potatoes, and cracker pudding. For supper, he ate boiled rice.

He also had time to reflect on his recent experiences in battle, writing,

Some may wonder how I felt while the balls and shells run across my back, and I knew not but that the next minute would be my last. I admit that I had rather been at home. But still I felt cool and knew everything that passed. […] I could only think of portions of the 91st Psalm. “A thousand shall fall at thy side, and ten thousand at thy right hand but it shall not come nigh thee.[”]

You can tell how relieved he was to be out of immediate danger. He took walks to local gardens and wrote with great appreciation of the natural world, the smell of English violets, the roses “bursting out.” He noticed the many beautiful birds wintering around New Bern, including robins, blackbirds, and woodpeckers, and was amused one morning to be awakened by a rooster. The woods teemed with game, and the river flowed “mostly without a ripple.”

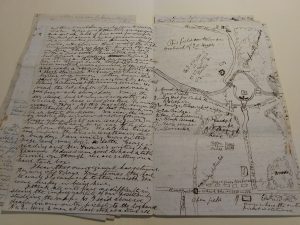

On 11 January 1863, Howard’s company was assigned picket duty about seven miles south of New Bern at a place called Evans’ Mill, formerly the plantation of Col. Peter G. Evans. Its job was to protect the operation of the mills. Howard drew a detailed map of the location.

Personally, I think the “Impassible Swamps” (at the top right) sound like something out of Tolkien. Notice, also, the row of buildings along the bottom labeled “Negro quarters formerly.”

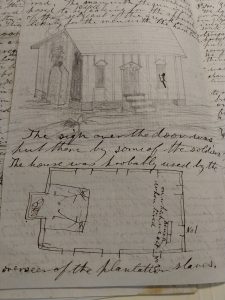

Howard was bunking with three other soldiers: his brother George and two fellow Cantabrigians, Pvt. Russell L. Snow and Cpl. James K. Odell. When the four men were assigned the “meanest” of the barracks, they decided to rebuild from the ground up. Fortunately, Pvt. Snow was a carpenter, and they finished in just over a week. They were proud of their “little hen house” and enjoyed the luxury of sleeping in a bunk and sitting at an actual table to write letters. Russell L. Snow, incidentally, would go on to build many buildings in and around Cambridge after the war.

But even in the relative comfort of camp, the life of a soldier was hard. Picket duty was particularly nerve-wracking, standing at alert for hours, fearing every night-time noise presaged an attack, “a twig crack here, a limb break there, a yell – a screech – a howl – a cry like a baby.” By now, Howard was accustomed to hardship and usually tried to make the best of things, but he had lost all patience for empty talk of patriotism.

I cant help thinking of Mr. Mason, Richard H. Dana or any other of our big guns who think it a fine thing to be one of those “who fought, bled and died” for the country, how patriotic they would look lugging down Magazine Street all day wood and water for the cook house, or perhaps taking their turn at washing the dirty pans and pails […] A person ought to have practical experience in those things of which he talks. Nothing like cold toes or a hungry stomach to make ones patriotism dwindle down.

In my next post, I’ll tell you what happened on 20 February 1863, what Howard described as “a great day in my term of service as a soldier.”