By Ian Delahanty, Springfield College, MHS Suzanne and Caleb Loring Fellow

Much was riding on the cotton crop that flowered on Port Royal Island in the autumn of 1862. Occupied by Union forces since November 1861, Port Royal soon became the focal point of a radical experiment in the employment of free Black labor. One of the people at the center of this experiment was Edward Atkinson, a Massachusetts industrialist and reformer whose status as a wunderkind of cotton textile manufacturing was preceded only by his reputation as a proponent of free labor. By 1857, the 30-year-old Atkinson managed six textile miles in New England. He had also devised a scheme to establish a colony of free Black laborers in western Texas and, in 1859, he would attempt to prove that imported African-grown cotton could supplant slave-grown southern cotton in the American market.[1] Secession and the outbreak of civil war in 1860-61 disrupted those plans.

But in 1862, Atkinson and dozens of other like-minded abolitionists and missionaries in Boston and New York concluded that African Americans’ productive and moral capacities in freedom could be demonstrated by the 8,000 or so newly freed people around Port Royal. In June, they formed The Educational Commission for Freedmen, an organization dedicated to the industrial, social, intellectual, moral and religious uplift of newly freed slaves. As one contemporary put it, “the success of a productive colony there [at Port Royal] would serve as a womb for the emancipation at large.”[2] In October, as boles of Sea Island cotton blossomed around Port Royal, Atkinson looked to have the cotton ginned in a manner that would render it as clean and as valuable as possible. He had one man in mind for the job: Eleazer Carver.

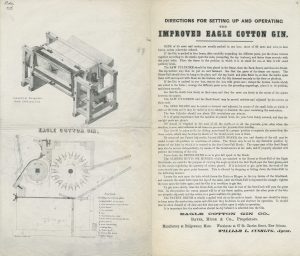

Carver is one of the central figures in my study of New England’s cotton gin manufacturers, which I’ve pursued at the MHS as the 2023-24 Suzanne and Caleb Loring Fellow. By 1862, he had nearly half a century of experience manufacturing cotton gins and was the proprietor of E. Carver Cotton Gin Company in East Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Having established himself as a reputable gin repairman and manufacturer after arriving in the Mississippi Valley in 1806, Carver returned to his native Bridgewater in 1817 and, with capital invested by the town’s thriving iron manufacturers, incorporated Carver, Washburn, & Co. as New England’s first gin factory.[3]

Carver-made gins set the industry standard in antebellum America. In 1853, the New York Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations, a sequel to London’s Crystal Palace Exhibition of 1851, awarded its second-highest highest honor to Carver’s gin. Alluding to a model of the gin patented by Eli Whitney in 1793 that stood at one end of the exhibition’s arcade, the prize jury noted that Carvery’s gin failed to win its highest recognition “only because Whitney did not leave room for improvements worth that reward.” This would have come as news to Carver, who over the previous quarter century had in fact patented numerous improvements on the cotton gin.[4]

Thus, with Sea Island cotton waiting to be ginned in October 1862, Edward Atkinson instructed one of the Port Royal colony’s superintendents to “have Carver … engaged to attend to the gins.” Upon learning that another official contracted to have the cotton ginned in New York, Atkinson was perplexed by this “adverse decision” and urged one of the colony’s superintendents to arrange for Carver to ship gins to Port Royal. Unfortunately, Atkinson’s papers yield no further information on whose gins cleaned the Sea Island cotton crop of 1862.

Why was Atkinson so intent on having cotton gins made in East Bridgewater, Massachusetts shipped to Port Royal, South Carolina? Part of the reason was that ginning the 90,000 pounds of cotton in New York at a premium of two to three cents per pound amounted to a loss of roughly $2,250.00 in profits. Then too, once the cotton was shipped to New York, the seeds separated from the fiber by the gins—seeds prized by Sea Island planters who knew the fickleness of long-staple cotton—could not be planted for next year’s crop.[5]

But Atkinson’s hopes of procuring gins specifically from Carver’s factory in East Bridgewater are also telling. As Atkinson noted in a May 1862 letter to one of the colony’s superintendents, the longer fibers of Sea Island cotton were prized by lace and muslin weavers in Britain.[6] But those fibers were severely damaged by the saw gins typically used to deseed the short-staple upland cotton that grew across most of the American South. Perhaps Atkinson planned to have Carver produce roller gins that, while less efficient than saw-toothed gins, left intact the longer fibers that were so valued by the agents of British muslin and lace factories.

Admittedly, this is speculation. But we do know that by the end of the Civil War, the E. Carver Cotton Gin Co. was producing roller gins. In fact, in April 1866, as 81-year-old Eleazer Carver gazed out of his bedroom window at the mill he had built, he asked an employee when a certain new roller gin model would be completed. Informed that it would be finished within a week, Carver replied, “I can live but a little longer, but do wish very much to see its operation.” He died the next day on April 6.[7]

[1] Frederick Law Olmsted to Edward Atkinson, May 5, 1858; Edward Atkinson to Thomas Clegg, April 20, 1859. Ms. N-298: Edward Atkinson Papers, Volume 1: Letterbook, 12 April 1853-28 December, 1860. Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston.

[2] Circular, “The Education Commission for Freedmen” (June 1862). General Correspondence, 1819-1920. Carton 1: 1819-1871. Ms. N-298: Edward Atkinson Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston; quote in Willie Lee Rose, Rehearsal for Reconstruction: The Port Royal Experiment (New York: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc., 1964), 31.

[3] M.C. McMillan, “The Manufacture of Cotton Gins, 1793-1860,” Cotton Gin and Oil Seed Press 94, 10 (May 15, 1993), 6-8.

[4] New York Exhibition of the Industry of all Nations, Official Report of Jury D: Machinery and Civil Engineering Contrivances (New York: DeWitt and Davenport, 1854), 12-13. Box 1854. Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston; Angela Lakwete, Inventing the Cotton Gin: Machine and Myth in Antebellum America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003), 80-92.

[5] Edward Atkinson to Edward Philbrick, October 14, 1862. Ms. N-298: Edward Atkinson Papers. General Correspondence, 1819-1920, Carton 1: 1819-1871. Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston; Rose, Rehearsal for Reconstruction, 204.

[6] Edward Atkinson to Edward Philbrick, May 19, 1862. Ms. N-298: Edward Atkinson Papers. General Correspondence, 1819-1920, Carton 1: 1819-1871. Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston.

[7] D. Hamilton Hurd, History of Plymouth County, Massachusetts, with Biographical Sketches of Many of Its Pioneers and Prominent Men (Boston: J.W. Lewis & Co., 1884), 866.