By Miriam Liebman, Adams Papers

In the summer of 1809 as John Quincy Adams prepared to set sail for St. Petersburg, Russia where he would serve as U.S. minister until 1814 with his wife Louisa Catherine and their son Charles Francis, he made plans for his two older sons, George Washington Adams and John Adams II, to stay with family in Quincy, much to his wife’s protest. While John Quincy had spent brief periods away from his children when he served as a U.S. Senator for Massachusetts in Washington, D.C., this would be the longest and furthest away he would be from his two older sons.

While he was in Russia, John Quincy wrote letters to his sons, who were now eight and six years old, for the first time. Previously, he would include brief notes or pieces of advice to them in letters addressed to either his wife or parents. As with his other letters from Russia, these were long letters filled with information and advice. In the letters to his sons, he focused on their education, writing, and penmanship, all highly valued skills by the Adams family. He also reminded his sons of their place in the world. He wrote, “you should each of you, consider yourself, as placed here to act a part— That is to have some single great end or object to accomplish; towards which all the views and all the labours of your existence should steadily be directed.”

Within these letters, he explained to his sons the family mandate: writing and recording one’s correspondence. This family practice went back to when his father, John Adams, first wrote of this idea to his mother Abigail Adams, on 2 June 1776 explaining how he had not kept a record of his correspondence and now purchased a folio book to keep track of his letters. John Adams did not wait long to pass this now family tradition on to John Quincy Adams. On 27 September 1778, John Quincy, while abroad in Europe, wrote to Abigail Adams about how his father taught him this same mandate. He wrote, “My Pappa enjoins it upon me to keep a journal, or a diary, of the Events that happen to me, and of the objects I See, and of Characters that I converse with from day, to day.” As he was only eleven years old at the time, he continued, “altho I am Convinced of the utility, importance, & necessity, of this Exercise, yet I have not patience, & perseverance, enough to do it so Constantly as I ought.”

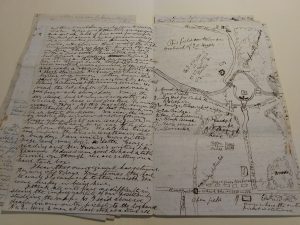

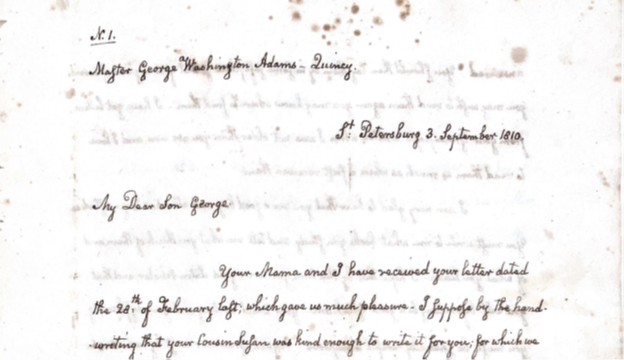

John Quincy did not wait until his sons were eleven years old to teach them the family practice and used his letters to his sons from Russia to introduce them to the family mandate. John Quincy provided practical advice for how George Washington Adams should keep track of his letters, a key part to preserving and recording one’s letters. The first step, according to John Quincy, was to keep all the letters he received from his parents. As part of this step, he advised his son to follow his lead and number the letters he sends. John Quincy wrote, “I have therefore numbered this letter at the top, and will continue to number those that I shall write you hereafter— Thus you will know whether you receive all the letters that I shall write you, and when you answer them you must always tell me the number or the date of the last letter you have received from me—.” In case George Washington Adams was not sure what his father meant, John Quincy told him to ask his uncle Thomas Boylston Adams how to number them, but also how to endorse and file them. He then suggested storing them in “some safe place” so that he could read them again if he wanted.

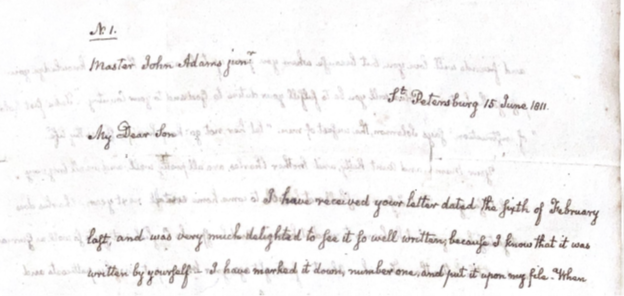

John Quincy provided similar instructions to John Adams II. Upon receiving his first letter from his second son, John Quincy “marked it down, number one, and put it upon my file.” While not providing the same detailed instructions, which George Washington Adams likely explained to his younger brother, John Quincy did have similar expectations that his second son would write him letters demonstrating his improved penmanship. He noted that since this began their individual correspondence, he noted it as number one, and that he was “very well pleased that you have resolved to keep your own file; and hope that it will be followed by an entertaining and instructive correspondence between us.”

With these letters sent to his sons thousands of miles away, John Quincy began to teach the next generation of Adamses the important family tradition of writing, recording, and preserving correspondence.

The Adams Papers editorial project at the Massachusetts Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the generous support of our sponsors. Major funding of the edition is currently provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, and the Packard Humanities Institute.