By Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

This is the fourth installment in a series. Click here to read Part I, Part II, and Part III.

In my last post about the Civil War journal of Howard J. Ford, I described his experiences in the Battle of Kinston, North Carolina, the first of three he would fight in quick succession during the Goldsboro Expedition of December 1862. Though his regiment, the 43rd Massachusetts Infantry, never engaged directly with the enemy at Kinston, I think you can tell from his journal that he was shaken.

He was also very tired. He and the other Union troops had already slogged through about 35 miles of difficult terrain, more than half the distance between New Bern and Goldsboro. The day after the battle, they ate a quick breakfast, shouldered their packs, and continued the march. Harold’s staccato sentences really convey the exhaustion.

The boys say that they had rather fight and run the risk of being killed than march. It is indeed severe. No one who has not tried it knows anything about it. Marching is not walking. O, how the load cuts in and draws down. Never mind. On, on. The roadside lined with the weak. Misery depicted on their faces.

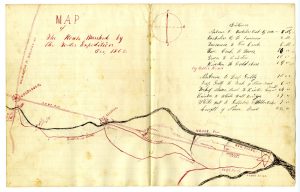

When doing historical research, I always like to try to orient myself geographically. I found this very helpful manuscript map of the Goldsboro Expedition drawn by a member of the 27th Massachusetts Infantry and digitized by the UNC Special Collections Library.

The location of the Battle of Kinston is indicated by the star to the left of the middle fold. The Battle of Whitehall took place a little further west, close to Goldsboro, on 16 December 1862.

I’d like to quote at length from Howard’s powerful description of the Battle of Whitehall because I couldn’t possibly do it better. I love his use of sound in this passage to evoke the chaos.

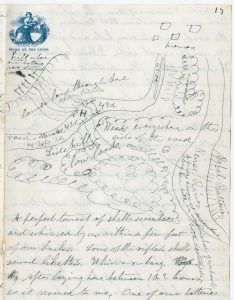

We marched till about 9 o’clock when boom, boom went the cannon in front. We halted in the road. We could hear now volleys of musketry which sound something [like] a boy pulling a stick along a fence. Then there would be a cannon fire followed in 2 or 3 seconds by the explosion of a shell. Boom, bang. Boom, bang. Lively. Crack (rifle) 4 or 5 Booms at once. &c &c ad infinitum. The artillery firing was the heaviest I had yet heard. […] We advanced a few hundred rods and halted. What we were here for is more than I know. We were placed between the fires of the opposing artillerists. We all fell flat on our faces. We laid closer to the ground than ever before. We all crawled into the gutters as low as possible, – colonel and all. Here we laid for 2 hours I should think expecting every moment would be our last. […] A perfect torrent of shells screeched and whizzed by us within a few feet of our backs. Some of the rifled shells sound like this. Whir-r-r-bang. […] You can hardly imagine the sensation while spread out there. I can never describe it.

Once again, Howard illustrated the battle in his journal, including features of the landscape and the relative positions of the batteries. The letter “H” in this drawing indicates Harold’s location on the road right between the Union and Confederate firing lines.

As I mentioned in a previous post, Howard was sending his journal home to Cambridge, Mass. in installments. I wonder what it must have been like for his parents, his siblings, and his wife Mary to receive these dispatches. I imagine them passing the pages around or reading them aloud to each other.

Join me in a few weeks for more on Howard J. Ford!