By Christy Pottroff, Ph.D., Boston College

A couple of years ago, I worked with a group of researchers to digitize a post office account book from Revolutionary-era Newport, Rhode Island. The book is a dataset in manuscript: it accounts for every piece of mail delivered to Newport residents by the colonial postal system between 1771 and 1774. This account book contains a wealth of information about life in colonial British North America in the years leading up to the American Revolution: about trade patterns, the dissemination of information, postal demographics. As a literary scholar, I had hoped that this dataset would shed light on the reading habits of Newport Residents during a moment of political upheaval. Did Newport’s postal users read more or differently in these final years of British colonial rule? What can we learn from these communication trends?

I put together a transcription team—(Thank you, Katie Reimer, Taylor & Katie Galusha, Melissa Lawson, and Sam Phippen!!)—to translate this book-based accounting system into a twenty-first century dataset. The work entailed entering the date of arrival, name of recipients, along with postage into columns of a spreadsheet. Such transcription requires a squint—eyestrain to make out the eighteenth-century handwriting. Once in a rhythm with transcription, there’s room for your mind to wander, to notice patterns in the text, and to speculate on the circumstances of postal use. It didn’t take long for our team to identify Newport’s postal “super-users”—George Rome, Aaron Lopez, and Simon Pease—men who received multiple pieces of mail every week. As we typed their names, we imagined their lives: were these men printers or preachers? Merchants, farmers, or teachers? Did they use the mail to incite Revolutionary fervor? Were they corresponding with friends or family at a distance? We wondered: how and why were these men using the mail every day?

The names we learned best—Rome, Lopez, Pease, and roughly 20 others—were all merchants, men with ships in a port city, sending banknotes and receipts through the mail. Roughly half of the mail that arrived at the Newport Post Office was addressed to the same top twenty-five postal users. These “super-users” were all men, and most built their wealth to some degree through the slave trade. They used the colonial postal system because it was the safest way to send large sums of money over long distances. In aggregate, the account book tells a simple truth: the colonial postal system largely abetted the economic interests of elite colonial subjects, fueled the slave trade, and only sometimes worked in the service of everyday Americans. This data-driven picture of the postal system appears much less democratic, and far from Revolutionary. The postal system was a tool for and network of the wealthy and powerful in early America.

When I started this project, I had hoped to find evidence of Obour Tanner in the pages of the Newport post office book. Tanner, a Newport resident, was the friend and lifelong correspondent of Phillis Wheatly (Peters). Tara Bynum, whose scholarly work introduced me to Tanner, describes the women’s letters as a source of joy, profound connection, and pleasure (see Reading Pleasures for more on their correspondence and networks—it’s an enlivening and important book). Though Tanner and Wheatley were enslaved at the time of their correspondence, both women found ways to bridge the gap between Newport and Boston through the exchange of letters.

And yet, they did not exchange their letters through the colonial mail. The Newport Post Office accounts contain no relevant entries for their letters during the period of their known correspondence. Few women appear in these pages at all (out of the over 8,500 pieces of mail that came into the office, only 125 items were addressed to women), and most of these women were white widows. No one in Tanner’s orbit received any mail by colonial post in the months of Wheatley (Peters)’s letters to Tanner. Instead, as usual, the colonial mailbag into Newport was largely filled with banknotes, receipts, and newspapers addressed to local merchants.

Meanwhile, outside of the colonial postal system, Obour Tanner and Phillis Wheatley (Peters) relied on their networks of friends and allies for the transmission of their letters. When she asks Tanner to send a reply to Mr. Whitwell’s, or to John Peter’s home, or by way of Rev. Samuel Hopkins, she “contextualizes and places herself as a friend, servant, slave, and woman in New England and the greater Atlantic world” according to Tara Bynum’s Reading Pleasures. When we read Wheatley’s letters for their postal systems, we see her integrated within a broader community of mutual aid: friends and allies who carried letters for one another.

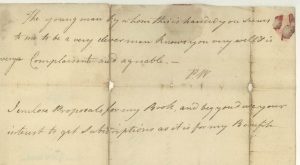

A letter from October 30, 1773 offers special insight into Wheatley (Peters)’s approach to long distance correspondence. The letter’s cover is spare—addressed simply “To—Obour Tanner in Newport,” folded, and sealed with red wax. As this letter was not sent through official postal channels, there is no postage denoted on the cover (and this letter long pre-dates envelopes, postage stamps, standardized cancellations, and other recognizably postal features).

Wheatley (Peters)’s closing note to Tanner offers a glimpse into its delivery. She writes: “the young man by whom this is handed you seems to me to be a very clever man knows you very well & is very Complaisant and agreeable. – P.W.” The letter was delivered by a friend, a man they mutually respected and admired for his intelligence, kindness, and demeanor. Phillis Wheatley (Peters)’s note on the letter’s delivery works to fortify and celebrate their friendship and mutual esteem. Was the clever letter-carrier close at hand when the poet finished her letter to Tanner? Did she read the line aloud to him with a smile and a wink—before folding and sealing the letter? Did this near-flirtation and unequivocal praise from a celebrated poet cause the man to blush? Or beam with pride? A letter delivered under these terms—directed through a statement of friendship and admiration—enlivened and encouraged community. Honoree Jeffers’ extraordinary scholarly and creative work in The Age of Phillis wonders whether this letter carrier might be John Peters, the man Phillis Wheatley would later marry. These letters testify to and were carried by people who cared for one another.

The colonial post office never delivered for Phillis Wheatley (Peters); but her friends did. First, during her lifetime, by establishing their own postal networks in which travelling friends and allies carried letters for one another. Then, Obour Tanner delivered Wheatley’s letters a second time—when she archived them with the Massachusetts Historical Society—thereby forwarding them to generations of readers and researchers.

When I started my fellowship at the Massachusetts Historical Society, I was motivated by Wheatley (Peters)’s long distance correspondence tactics, Tanner’s archival efforts, and I was skeptical of overly celebratory narratives of postal history. While my book-in-progress studies the United States Post Office Department rather than the colonial-era system, the mailbag’s mercantile allegiance endured throughout the nineteenth-century, as did the mail’s race and gender-based exclusions.

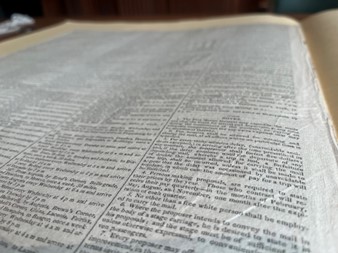

In the archive of the Massachusetts Historical Society, I encountered historical materials that further attuned my thinking about the allegiances and exclusions of the US Post Office Department. When I read the enormous 4-page broadside “Proposals for Carrying Mails in the United States” I was first struck by the sheer size of postal operations in 1824. The Postmaster General advertised contracts for mail carriers on nearly 400 routes throughout the country—each printed in small font covering every inch of the oversized pages. Each route paid a sizable sum: an amount the USPOD presumed would cover the operating expenses for a stagecoach line (which contractors would then supplement by selling passenger tickets and by carrying small freight). Each contract was an avenue into middle class life, geographically distributed throughout the length and breadth of the country. And yet, “no other than a free white person shall be employed to carry the mail,” the broadside advertises. Not only were these nearly 400 lucrative contracts awarded on a whites-only basis, the lower paid postrider and mailcoach driver positions were likewise closed off to Black Americans. The formal exclusion of Black labor from the postal system further extended to local postmasterships and clerkships. This racial exclusion existed until the end of the Civil War, and had a profound influence on the distribution of wealth along racial lines in the nineteenth century. In this period, the US Post Office Department was the largest employer in the country, and it only handed out jobs to white people. I was left with enduring questions about the broader social effects of this policy—would white postmasters serve Black correspondents? In what ways would a postmaster’s surveillance curtail textual expression, connection, and circulation?

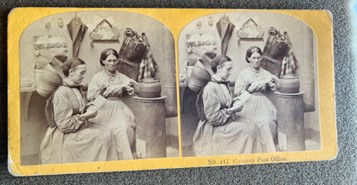

Later, when scouring every detail of the photo “Country Post Office,” I wondered about the locks and the highly-specialized leather portmanteau hanging on the wall behind the women reading their letters. The Post Office Department commissioned state-of-the-art locks and distributed the keys only to local postmasters. The leather portmanteaus worked in tandem with the locks to secure the mail and protect the contents from water. When read in tandem with the photo’s more central figures—the reading women—I’m reminded of the ways the post office in the nineteenth century worked on behalf of some Americans and worked to lock-out others. The post office delivered for these women—it offered a place of respite where they could read, warm themselves after their walk to the local office. At the same time, the locks are testaments to the exclusionary nature of the postal system in the nineteenth century—a network that both shaped and constrained communication.

These archival encounters helped me reframe my longstanding postal research to be better attuned to both the possibilities and prohibitions of the mail. Postal Hackers—the project’s new title—tells the stories of the nineteenth-century outsiders who laid claim to postal resources and sometimes broke the system that structured their exclusion. The project is motivated by the ingenuity of hackers like Henry “Box” Brown who used a private express company to mail himself out of enslavement; and by Harriet Jacobs whose letters conveyed by hand from a tiny attic crawlspace and put in the mail in Northern cities (thereby receiving location-based cancellation stamps) convinced her enslaver to seek her out in the North. Brown and Jacobs’s strategic use of the postal system allow them to find spaces of freedom and safety on their own terms. My book project also highlights the petition of Mary Katherine Goddard—Baltimore’s revolutionary era postmistress, who was fired for being a woman in 1790. Though she never got her job back, Goddard’s textual campaign—a petition signed by 250 men from Baltimore, a letter of support from George Washington, and her own newspaper writing on the matter—measure important changes in postal power in the early national period. Taken together, these stories help measure the particular nature of postal authority; the economic allegiances of the Post Office Department, as well as the social and literary effects of postal incorporation.

Thinking through the collections at the Massachusetts Historical Society was integral to this project. The collections helped refine and clarify my understanding of the nineteenth-century postal context. Just as powerful was the effect of drafting Postal Hackers from the same building that houses Phillis Wheatley’s writing desk and her unstamped, community-building letters. These materials testify to the limits of state postal systems—as well as the fortitude and creativity of Black letter writers who relied on their own networks for the exchange of letters.

Further Reading:

- Bynum, Tara. Reading Pleasures: Everyday Black Living in Early America. University of Illinois Press, 2023.

- Bynum, Tara, Brigitte Fielder, Cassander L. Smith, eds. Special Issue “Dear Sister: Phillis Wheatley’s Futures,” Early American Literature 57.3 (2022).

- Jeffers, Honorée Fanonne. The Age of Phillis. Wesleyan University Press, 2022.