By Kathryn Lasdow, Assistant Professor of History, Suffolk University, Boston

It might surprise readers of this post to learn that women played a significant role in Boston’s late-colonial and early-national real estate market. Who were these women, and what kinds of properties did they own or rent? What impact did they have on the evolving cityscape of the bustling port? The traditional narrative of Boston’s urban development has mainly focused on the contributions of men—businessmen, merchants, and craftsmen—who envisioned, funded, and built the city. However, what has intrigued me most about Boston’s evolution is the involvement of women as property owners, renters, and occupants. As a NEH Long-Term Fellow, I uncovered this hidden history while undertaking revisions for my forthcoming book Wharfed Out: Improvement and Inequity on the Early American Urban Waterfront. Here are two stories drawn from MHS collections that shed light on the presence and influence of women in Boston’s early real estate market.

Hannah Rowe’s Wharf: Inheritance and Financial Know-How

In 1787, Hannah Rowe inherited waterfront real estate valued at $20,000 from her late husband, John Rowe.[1] As a widow, Hannah no longer faced the legal constraints of coverture, which stipulated that a woman’s property became her husband’s upon marriage. The wharf once synonymous with his successful merchant business now belonged to her, making her one of the most economically powerful waterfront real estate owners in early national Boston.

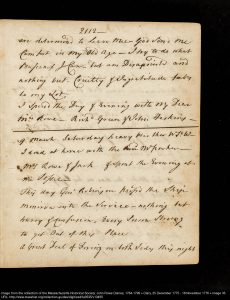

When looking for Hannah Rowe in the archive, I delved into sources left behind by her husband to uncover evidence of her proximity to merchant business. John’s diary, a meticulous but concise record that he kept in the 1760s and 1770s, corresponded to Hannah’s life in middle age. John frequently mentioned counters with “Dear Mrs. Rowe” and his business associates as they navigated the economic challenges posed by the American Revolution and its impact on the wharf.[2] Hannah was present for many of these conversations and likely listened to and participated in them. John mentioned how she “assisted [him] very much.”[3] [See Fig. 1]

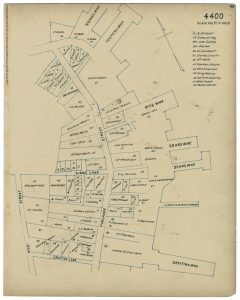

However, it was Hannah’s real estate transactions during her widowhood, spanning approximately eighteen years from her husband’s death in 1787 to her own death in 1805, that truly showcased her financial skill. I examined both the Samuel Chester Clough Atlases and the “Inhabitants and Estates of the Town of Boston, 1630-1822” (Thwing database) to uncover Hannah’s strategic purchase of various properties. [See Fig. 2] Hannah engaged in at least twenty-four property transactions, managing a diverse portfolio that included parcels of undeveloped land, homes, warehouses on Merchant’s Row, the Lamb Tavern, and water rights along the harbor.[4] She used mortgages as an investment opportunity and a means to safeguard her funds through real estate holdings.

Hannah Singleton’s Plight: Boarding House Keeping and Renting

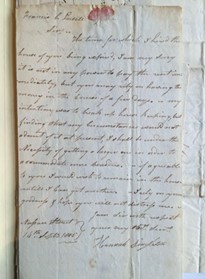

For women of modest means, the journey to property ownership was more complex. Financial precarity often pushed women to rent rather than shoulder a mortgage burden. This was certainly the case for Hannah Singleton, a widow who leased a house from merchant Francis Cabot Lowell and struggled to run a boarding house. In the Francis Cabot Lowell Papers, I unearthed a letter she wrote to Lowell in September of 1805. [See Fig. 3] “I’m very sorry,” Hannah wrote, “it is not in my power to pay the rent immediately.” She assured him that she would have the money in a few days and pleaded with him to allow her “to remain in the house until [she could] get another.” Aware of Lowell’s position as her landlord, Hannah implored him not to “distress” her.[5]

In this brief exchange, we see Hannah Singleton attempt to navigate the fluctuating real estate market while beholden to a male landlord. The sources do not reveal her fate, but she may have remarried. The 1806 tax assessment lists a woman named Hannah Doane on Nassau Street, the same street where Hannah Singleton’s boarding house was located.[6]

The stories of these two Hannahs in early Boston demonstrate that women found ways to work within and transcend societal expectations regarding female financial behavior, making their own significant impact on the waterfront and the urban landscape.

[1] See multiple entries for Hannah Rowe in “A Report of the Record of Commissioners of the City of Boston, containing the . . . Direct Tax of 1798” (Boston: Rockwell and Churchill, 1820).

[2] Diary entry, March 8, 1776, John Rowe Diaries, 1764-1779, Ms. N-814, Massachusetts Historical Society, https://www.masshist.org/collection-guides/view/fa0535

[3] Diary entry, March 11, 1776, John Rowe Diaries, 1764-1779, Ms. N-814, Massachusetts Historical Society, https://www.masshist.org/collection-guides/view/fa0535

[4] Deed between Hannah Rowe and Perez Morton, May 12, 1787, SD 160:115; Deed between Hannah Rowe and Isaiah Doane, May 12, 1787, SD 160:118; Deed between Hannah Rowe and Thomas Bulfinch, August 2, 1788, SD 163:115; Deed between Hannah Rowe and Samuel Cookson, July 11, 1788, SD 163:133; Deed between Hannah Rowe and Ezra Whitney, August 24, 194, SD 181:91, Thwing Database.

[5] Hannah Singleton to Francis Cabot Lowell, September 14, 1805, Francis Cabot Lowell Papers, Ms. N-1603, MHS.

[6] Boston City Directory 1806, Boston Athenaeum Digital Collections, https://archive.org/details/bd-1806, 45.