By Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

This is the third installment in a series. Click here to read Part I and Part II.

Since my last I have seen experiences which are new and and [sic] startling. Only by the blessing of God have I got through unharmed. I think that all have seen marching and fighting enough to last them a lifetime. Our best boys begin to wish they were at home. Some of the best and most patriotic are discouraged and willing to end the war on any terms.

These are the words Pvt. Howard J. Ford wrote in his Civil War journal after seeing combat for the first time. What follows are several pages describing his experiences during what came to be known as the Goldsboro (or Goldsborough) Expedition, including the battles of Kinston, Whitehall, and Goldsboro Bridge, N.C.

In two previous Beehive posts, I wrote about Howard’s life prior to his service with the 43rd Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, as well as his enlistment and training. But it was his descriptions of battle that really drew me to this collection in the first place. I’ve rarely seen personal accounts from this time that paint such a vivid picture of what war actually feels like.

Just three weeks after his arrival in the South (specifically New Bern, N.C.), Howard was already hearing rumors that his regiment would be deployed. He prayed most of all for “perfect calmness” in battle, writing on 7 December 1862, “I want to be ready with nothing to do but to attend to my business.” Sure enough, his readiness would soon be tested by three battles in quick succession.

On 11 December at 5:30am, the 43rd Mass. Infantry and other regiments set out from New Bern as part of Brig. Gen. John G. Foster’s big push to Goldsboro, N.C. Goldsboro played a vital role in the Confederate supply chain. It was a major junction on the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad, which brought troops and supplies up from the port of Wilmington. Foster was on a mission to disrupt that supply chain by destroying the Goldsboro Bridge. Along the way was the town of Kinston.

The march from New Bern was grueling. Surrounded by “dismal & gloomy” pine woods, the troops had to ford streams, trudge through mud, and climb over large tree trunks that the Confederates had placed across the road to slow them down. Rations were low, and packs were heavy.

Early in the march, Howard saw signs of recent fighting, including dead and wounded Confederate soldiers and shell damage to trees. On the third day, he heard nearby shelling for the first time, and the danger suddenly felt very real. He wrote, “Of course we pricked up our ears somewhat. Some began to turn pale and fret. I tried to think it was nothing of consequence.” His regiment set up camp in an open field surrounded by trees, out of which, Harold feared, the enemy might fire at any minute. An army doctor demonstrated how to make a tourniquet with a handkerchief.

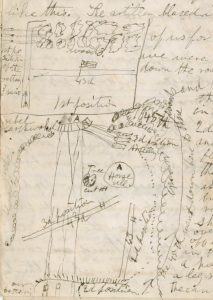

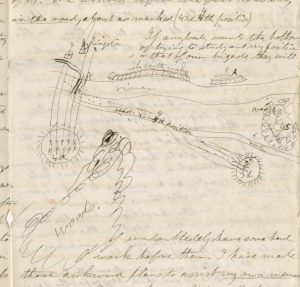

The Battle of Kinston was fought the next day, 14 December 1862. Although the 43rd Mass. Infantry was present, it was held in reserve, and Howard never engaged directly with the enemy. He wrote, “I suppose an old soldier would laugh at the dangers to which our regiment was exposed but for green troops it was something.” His descriptions of the battle are very detailed, cover more than six pages, and include maps and illustrations.

But when it comes to the chaos of war, words and pictures fall short, even Howard’s. He noted, “It is very difficult to give a distinct idea of this or any battle. The few things I have referred to were occurring with great rappidity [sic] and several at the same time in some cases. We forgot our danger in the excitement of the occasion.”

Just two days later, Howard would face more fighting, and this time he’d be in the thick of it. Stay tuned for the next installment.