By Meg Szydlik, Visitor Services Coordinator

For this blog post, I thought I would return to my more science-y roots. I mentioned in a previous blog post that I was raised in a family with a lot of focus on science. One of the ways we did that was rocket launching. As a child, I used to launch all kinds of rockets. While explosives are not my preferred experimental matter, I do have very fond memories of building and launching these (air-pressurized and non-explosive) rockets hundreds of feet into the air. With July Fourth approaching, I thought it would be the perfect time to explore some MHS materials on fireworks and rockets while reminiscing about my own experiences. Our collections have quite a few fireworks-related material, but one of the most interesting is a how-to book called Artificial fireworks : improved to the modern practice, from the minutest to the highest branches which includes recipes and illustrations so that you too can make big, colorful 1776 fireworks.

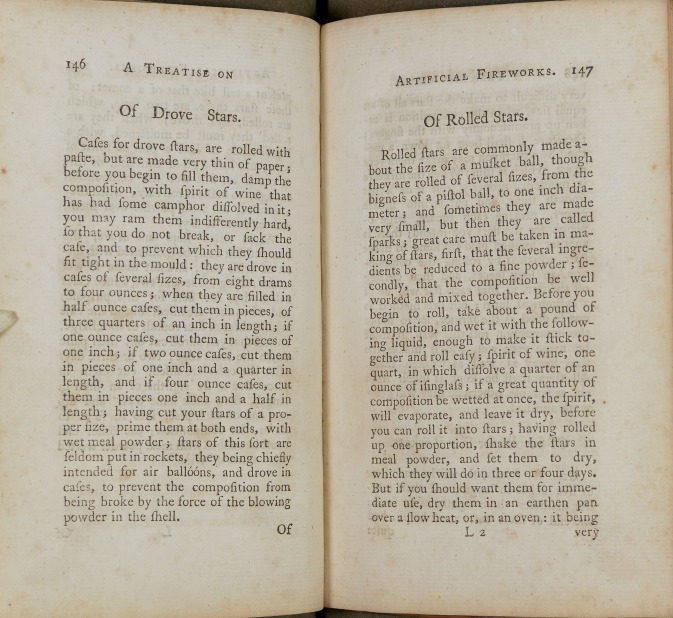

I elected not to create any of these fireworks myself, not least because I don’t think I can just roll up and purchase a lot of these ingredients without ending up on a government watchlist. But it was a very interesting read nonetheless! The author was an officer in the British Army and his writing style reflects the terse, clipped language I associate with military efficiency. Brisk, but clear and easy to read once you get past the ſ, or long s, in place of our modern round s. I learned that if you add the right kind of minerals, you can make virtually any color in a variety of shapes and showers. Different materials alter the color of flames, a fun experiment if you have a fireplace and a penchant for risk-taking. To make white fireworks, use saltpeter, sulfur, meal powder (also called black powder), and camphor. To make blue, the ingredients are saltpeter, sulfur, and meal powder. To make red, add saltpeter, sulfur, antimony, and Greek pitch (aka rosin). And voila! Everything you need to make your own fireworks–except measurements. While some of the recipes do have measurements, they are not nearly as precise as I would expect explosive recipes to be.

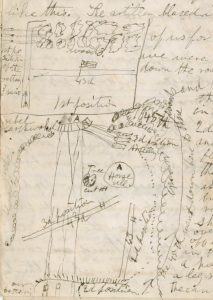

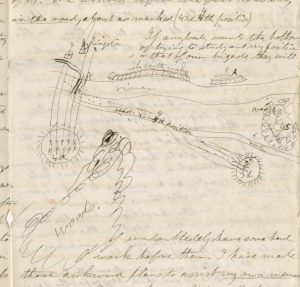

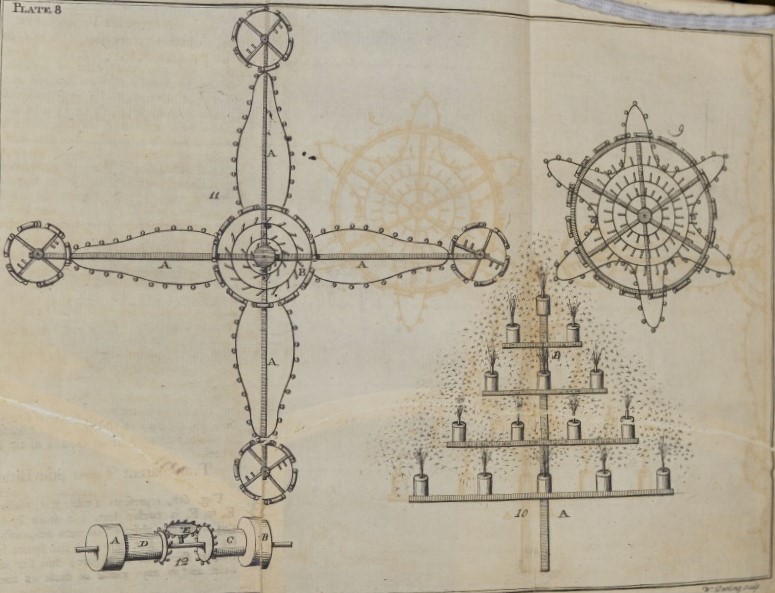

Unclear measurements and temperatures are a chronic problem in old cookbooks and one that has been well documented in other Beehive blog posts, such as this one about bread pudding. So in many ways, this is just like so many recipe books in our collection, despite not being nearly as delicious. Do not worry, though—if you want to make a case, aka the rocket body to hold the fireworks, those come with detailed mechanical instructions and illustrations! I actually feel pretty good about my ability to put a case together, assuming I had the pieces and did not have to learn how to cut steel. I am confident that I could learn, but a girl needs some limits, even in her imagination.

Personally, I would recommend sticking to modern fireworks over making your own 18th century ones. Though if you do feel so inclined, feel free to head on down to the MHS and examine the book yourself! In the meantime, enjoy those Fourth of July fireworks and festivities knowing it’s a little safer than in 1776.