By Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

This is the second installment in a series. To read Part I, click here.

A few weeks ago, I introduced you to Howard J. Ford and his Civil War journal, held by the Massachusetts Historical Society. The MHS holds many collections related to the Civil War, of course, but this journal is truly remarkable. It’s not often we get such an honest and intimate look at a soldier’s inner life.

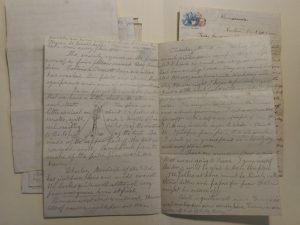

On 4 September 1862, Howard J. Ford of Cambridge, Mass. enlisted for nine months’ service in the 43rd Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. He started his journal one week later, on the day he reported to Camp Meigs at Readville, Mass. I call it a “journal,” but it really consists of loose pages of stationery that Howard initially titled “Memoranda” and sent home at intervals over several months.

Howard and his younger brother George were mustered in as privates on 24 September. The first few pages of Howard’s journal contain brief, dashed-off entries about life in camp, equipment issued, duty details, and the weather (mostly rain). But the 43rd Regiment was stationed at Readville for just six weeks, leaving from Boston Harbor on 10 November 1862. Their destination was New Bern, North Carolina.

The weather seemed to bode well. As Howard wrote, “This morning the sun shines and he seems almost like a stranger.” The men sang “Home, Sweet Home” as their ship pulled away from shore. And Howard made the following pledge in his journal: “I dont [sic] intend to come home if I have […] to save my life by being a coward or disobeying orders. Howard.”

His ship, the Merrimac, and two other troop ships, the Mississippi and the Saxon, traveled as a convoy under the protection of a gunboat, the Huron. The voyage was relatively uneventful, except for the usual bouts of seasickness and an accidental shooting. (Lt. Henry A. Turner shot himself in the foot “in consequence of carelessly handling his pistol while cocked.”)

When Howard disembarked in North Carolina on 15 November, he was unimpressed, calling it “a mean sort of a place.” Traveling inland, he described the landscape in more detail, including soil that was a combination of “sand & swamp”; architecture (“chimney on the out side of the house”!); and “that peculiar moss hanging [from trees] in pretty festoons.” He also began to see “contrabands,” or enslaved people who had escaped bondage and now worked for or sold goods to Northern troops.

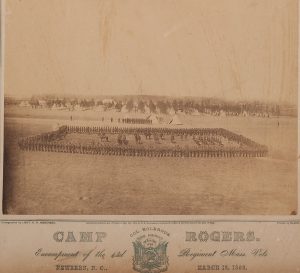

The Union camp, later named Camp Rogers, was located on the southern bank of the Trent River. But even though Northern troops had occupied New Bern for the past eight months, Howard was disappointed to find “no tents, barracks or food ready for us.”

His journal entries at New Bern contain a lot of vivid descriptions, even a few sketches. For example, here’s how he explained a skirmish drill to family members back home:

In this style of fighting the men keep at least 5 paces apart, so that it is more difficult to hit them than in the ordinary way. We also move more rapidly. It is lively work. One minute we are scattered over a long line, and the next rallied by fours, or perhaps sections or platoons. All up in a cluster with our bayonets looking like a porcupine sticking out in every direction to keep off cavalry. Sometimes we load and fire lying down, kneeling, advancing, retreating.

Howard knew Confederate troops were positioned nearby and that the next battle was probably imminent. He told his family that he anticipated having “a chance at the rebels” within the month. When each soldier was issued twenty rounds of ammunition, he wrote ominously, “This looks warlike.”

Stay tuned for more about Howard J. Ford in my next post!