By Juliane Braun, Auburn University

Between November 1789 and January 1790, the two American ships Columbia Rediviva and Lady Washington arrived in the Pearl River Delta, ready to sell their precious cargo. Captained by John Kendrick and Robert Gray, the two ships had set out from Boston in 1787 to sail to the Pacific Northwest, where they were to acquire sea otter furs furnished by Indigenous traders and hunters. These furs promised to generate significant profits, if Kendrick and Gray managed to bring them to Canton (Guangzhou) unspoilt, and if they succeeded in navigating the ins and outs of the complicated Canton market.

The Canton system was closely regulated by the Emperor, and Kendrick and Gray likely relied on reports from Samuel Shaw, a Boston man who had served as supercargo on the first American trading vessel in Canton for insights on how to deal with the Chinese authorities. Shaw had noted how each foreign trader could only sell his cargo if he enlisted the services of a set of government-licensed Chinese agents: The first was a “fiador” or security, who was in charge of collecting port fees once a ship entered Cantonese waters, the second was a “comprador,” who supplied each foreign vessel with provisions and other necessaries, and the third was a “linguist” through whom all foreign trade had to be conducted (Shaw 346-349).

I came to the MHS specifically to learn more about Kendrick and Gray’s endeavor to sell their sea otter skins in Canton, and about the early transoceanic trade between the United States and China more generally. Like Kendrick and Gray, I was initially quite overwhelmed with what I found. The MHS houses one of the largest collections on the early US-China trade in the United States, and even though I had as a guide Katherine H. Griffin and Peter Drummey’s article on the MHS’s China trade holdings, it took me months to fully grasp the wealth of the collections. As I read my way through journals, correspondence, notebooks, accounts, and shipping papers, I became increasingly fascinated with the Canton linguists and their crucial role in all trading activities.

The linguists served as the official mediators of all exchanges between foreign traders and the Chinese authorities. In Kendrick and Gray’s case this meant that they examined the sea otter skins to assess their quality, determined if an offer should be made and at what price, and managed payment (Howay 133-135). They were also in charge of procuring the necessary paperwork and customs seals and they acted as translators. Intriguingly, however, the linguists did not actually speak English or any other foreign language well. Linguists were in fact discouraged from becoming too fluent in any foreign language because fluency indicated that a linguist had become too sympathetic to foreign concerns (Van Dyke 290). How, then, was this trade conducted when Europeans and Americans did not speak Cantonese and Chinese linguists only knew “broken” English? How did linguists and traders navigate language and cultural barriers? And to what extend did misunderstandings, mistranslations, and communication gaps affect the trading activities?

I do not have the answers to these questions yet, but I suspect coming closer to them may involve the notebooks of American trader William P. Elting and the Chinese merchant Houqua, as well as a closer look at the emergence of Cantonese Pidgin English (CPE), an English jargon that linguists and traders alike began to resort to to negotiate their exchanges. Although Kendrick, Gray, and the linguist assigned to them likely already communicated in CPE, they only managed to sell their 700 sea skins with “the greatest trouble and difficulty” (Howay 133). The prices they fetched were underwhelming. Gray returned to the United States in 1790, only bringing back cheap bohea tea, and none of the luxury items and Chinoiserie he and Kendrick had hoped for. He could console himself with being the first American to circumnavigate the globe.

Sources:

Columbia Papers, 1787-1817. Massachusetts Historical Society. Special Colls. Columbia.

William P. Elting Notebook, 1797-1803. Massachusetts Historical Society. Ms. N-49.19

Katherine H. Griffin and Peter Drummey, “Manuscripts on the American China Trade at the Massachusetts Historical Society.” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society Vol. 100 (1988): 128-139.

Houqua Letterbook, 1840-1865. Massachusetts Historical Society. Ms. N-49.32.

Frederic W. Howay, ed. Voyages of the “Columbia” to the Northwest Coast, 1781-1790 and 1790-1793. Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1941.

Samuel Shaw and Josiah Quincy. The Journals of Major Samuel Shaw, the First American Consul at Canton, with A Life of the Author, by Josiah Quincy. Boston: Crosby and Nichols, 1847.

Samuel Shaw Papers, 1775-1887. Massachusetts Historical Society. Ms. N-49.47.

Paul Arthur Van Dyke, “Port Canton and the Pearl River Delta, 1690-1845.” Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Southern California, 2002.

Image:

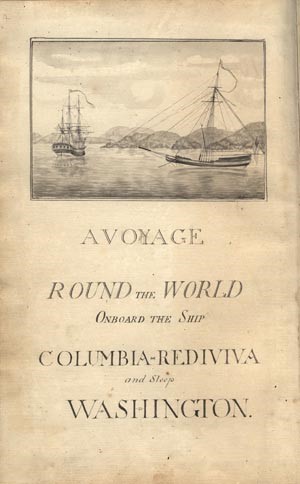

Robert Haswell. Voyage Round the World on Board the Ship Columbia Rediviva and Sloop Lady Washington, 1787-1789. Massachusetts Historical Society. Special Colls. Haswell.