By Emily Petermann, Library Assistant

Relief Printing: to carve away at a block of medium– often wood, linoleum, or metal–leaving behind a raised image that will be inked and printed onto paper. This type of printing is often referred to as letterpress printing and was the primary form of printing from Gutenberg to the 20th century.[i]

Although women have always been a part of industry, their work has been undervalued and underrepresented in the historical record. The contributions of women have regularly been portrayed as somehow deficient or unequal to the work of their male counterparts. Women are often not even considered in many historical writings but are rather resigned to the background–carved away, to leave the relief-print of men at work.

In the Colonial period, printing was hard, but vital work. Women often filled these vital roles in printing, working alongside men as printer’s devils and compositors, for example. Yet their names were often not recorded and thus they are not easily seen in history.

Today we will explore the MHS collections to find the imprints of the women who were part of the Early American Printing Industry: Ann Franklin, Sarah Goddard, and Mary Katherine Goddard.

Ann Franklin: 1734-1763

Like many women in the early printing industry, Ann Franklin came into the business through the death of a male relative; her husband, James. Franklin had previously taken over the press while James was in prison, and at a time when her brother-in-law, Benjamin (yes, that Benjamin Franklin) had fled to Philadelphia.[ii] Following the death of James in 1735, Franklin took on the family printing business in Newport, RI. In 1736 she became the Colony Printer,[iii] which meant that she printed all of the new legislative and official documents. In addition to printing books and pamphlets, Franklin also edited, printed, and published a newspaper titled The Newport Mercury.[iv] At a time when women had little legal standing, Franklin, as a businesswoman and widow, was able to run the business like any man: forming and dissolving partnerships, pursuing contracts, and expanding the business. Franklin would run the shop until her death in 1763.[v]

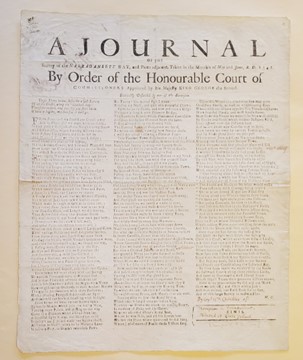

The MHS has a few items published by Ann Franklin, including this broadside titled “A journal of the survey of the Narragansett Bay, and parts adjacent” by William Chandler, which Franklin printed in 1741.

To find other materials in Abigail published by Franklin, perform a keyword search for “Widow Franklin” and “Ann Franklin”.

Sarah Goddard, 1765-1768

Sarah Goddard was introduced to the world of printing in 1762, when her son William chose to open a printing shop in Providence, RI. Sarah and her daughter, Mary Katherine, moved to Providence to support him in his business. Instead, William’s attention would soon be drawn to other lines of business, leaving Sarah and Mary Katherine to manage the press in his absence: Sarah, who owned a share in William’s press, managing the business, with Mary Katherine as a compositor.[vi] In 1766, Goddard took public ownership of the press, as the imprint became “Sarah Goddard and Company.” Like Franklin, Goddard was legally able to form partnerships and pursue contracts. One such partnership, formed in 1767, was with John Carter, who had been apprenticed to Ann Franklin’s brother-in-law. Goddard and Mary Katherine ran the business in Providence for many years, until William decided to set up another printing shop in Philadelphia. The Goddards sold the Providence shop to Carter and followed William to Philadelphia, where Sarah Goddard died in 1768, shortly after the move.[vii]

The MHS holds one item published by Sarah Goddard and Company: a pamphlet titled “Divine Providence illustrated and improved” by David S. Rowland, published in 1766.

Mary Katherine Goddard, 1774-1784

Mary Katherine Goddard came into the printing industry with her mother, Sarah Goddard, first as a compositor in Providence, RI and then in Philadelphia. Upon her mother’s death in 1768, she assumed ownership of her mother’s share in her brother William’s business, and management of the print shop as a whole.[viii] Four years later, in 1772, William again moved the print shop, this time to Baltimore. Once more, Mary Katherine followed her brother to manage the operation.[ix]

Mary Katherine eventually left her brother’s shop and began her own, competing press, publishing under the imprint “M.K. Goddard.”[x] While managing her own press, Goddard also served as the Baltimore Postmaster from 1775-1789. She was forced to relinquish that title in 1789 when the postal system was consolidated; at that time, over 200 Baltimore businessmen attested that she was well deserving of the title and position.[xi] In 1777, Goddard‘s press was the first to print the official Declaration of Independence with the signatures attached 7.[xii] Eight copies of Goddard’s printing of the Declaration of Independence still exist; you can see one here, held by the New York Public Library.

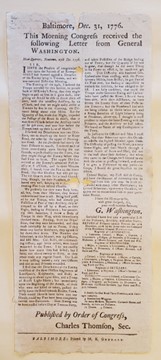

Although we would love to say that we hold the other copies, in fact, the MHS holds one item published by M.K. Goddard: “Baltimore, Dec. 31, 1776. This morning Congress received the following…”

These women made, and quite literally, recorded early American history. Franklin, as one of the first female printers in the British Colonies, Sarah Goddard as she ran multiple printing shops, and Mary Katherine Goddard as she printed the first signed edition of the Declaration of Independence, all played a vital role in the transition of the colonies to a nation. There are, of course, more such women whose lives were not recorded in the same way as Franklin and the Goddards. These three women are among the many whose work has been undervalued and underrepresented in the historical record.

I hope you enjoyed a quick look into the history of women in Early American Printing history!

[i] Sidney E. Berger. “Relief Printing,” The Dictionary of the Book : A Glossary for Book Collectors, Booksellers,

Librarians, and Others. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2016. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=1351166&site=eds-live&scope=site.

[ii] Leona M. Hudak. Early American Women Printers and Publishers, 1639-1820.

Metuchen: Scarecrow, 1978.

[iii] Frances Hamill. “Some Unconventional Women Before 1800: Printers, Booksellers, and

Collectors” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 49, no. 4 (1955): 300-314.

[iv] Leona M. Hudak. Early American Women Printers and Publishers, 1639-1820.

[v] Hudak. Early American Women Printers and Publishers, 1639-1820.

[vi] Hudak. “Early American Women Printers and Publishers, 1639-1820.”

[vii] Hudak. “Early American Women Printers and Publishers, 1639-1820.”

[viii] Hudak. ”Early American Women Printers and Publishers, 1639-1820.”

[ix] S tate of Maryland Archives. “Mary Katherine Goddard (1738-1816).” Archives of Maryland. https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/002800/002809/html/2809bio.html

[x] State of Maryland Archives. “Mary Katherine Goddard (1738-1816).” Archives of Maryland.

[xi] State of Maryland Archives. ”Mary Katherine Goddard (1738-1816).”

[xii] Hamill. ”Some Unconventional Women Before 1800: Printers, Booksellers, and Collectors.”