By Klara Pokrzywa, Library Assistant

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw a plethora of innovations in photographic development. As photographic reproduction technology became more widely distributed, both professional and amateur photographers had the opportunity to experiment with different ways of capturing images. While it may be hard to imagine today, when most photographs are taken with a single tap on a smartphone screen, early photographs widely varied in their methods of documenting the world around them.

One early photographic technique I find particularly interesting is the cyanotype method. By bathing paper in a mixture of iron salts and potassium ferricyanide, and then exposing the treated paper to light, a photographer can capture images in distinctive shades of Prussian blue—a rich near-indigo color that gives cyanotypes an immediately identifiable aesthetic.

This process was invented by English photographer John Frederick William Herschel in the 1840s—but perhaps its most iconic images were created by his acquaintance Anna Atkins, a botanist who used the cyanotype process to create photograms of seaweed, algae, and ferns. Now considered the first female photographer, Atkins had a keen eye for artistic detail and composition that ensured her images are celebrated everywhere from the Getty Museum to the MOMA.

I’ve long been interested in cyanotypes for their vivid monochromes and fascinating history, and have occasionally gone out of my way to find exhibits on them, such as the Provincetown Art Association and Museum’s Out of the Blue show from last fall. So I was happy to recently discover that ABIGAIL, our online catalog, has a subject heading under which our cyanotype holdings are cataloged! This made it easy for me to explore what kinds of cyanotypes we have here at the MHS—and I certainly wasn’t disappointed.

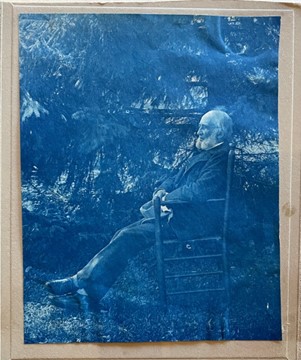

Many of our cyanotypes depict domestic scenes and personal, poignant snapshots. In the below photograph, a grandfatherly man reclines in a garden, the textures of his clothing and the trees surrounding him picked out in stunning pacific blues. The monochrome coloring mimics the cool shade of the trees, making the scene’s careful composition and use of light a snapshot of private peace.

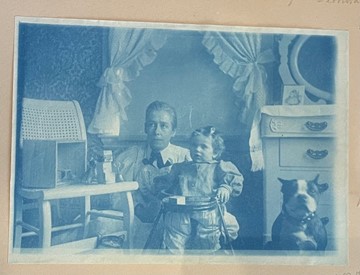

Perhaps because we’re used to seeing old photographs in black and white, the cyanotypes feel particularly alive—details jump out at me more in blue, and make moments that break the serious propriety so often (and wrongly) associated with old photographs feel even more vivid. The presence of a dog (maybe a pitbull?) in the lower right hand of the below photograph is especially delightful in the below image: blurry and wide-eyed, its startled stare into the camera feels like an ancestor of the many pet photographs stored on my phone.

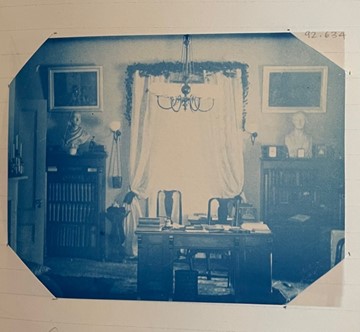

Sometimes, though, the blued lens of a cyanotype can lend a melancholy cast to an otherwise neutral tableau. In the below photograph, the lit window of an empty room appears almost ghostly to me, blotting out the details of the scene with periwinkle sheen.

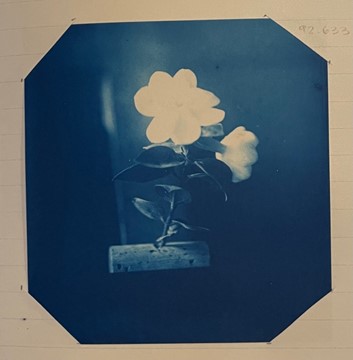

Similarly, the careful, minimalist composition in the following images of flowers feels a little lonely when rendered in blue—what might have merely been pretty in color appears wistful in monochrome.

Artistic interpretations aside, cyanotypes were an easy and cheap method of photographic reproduction, commonly used before the advent of other, later methods of film reproduction. Their low barrier to access meant that their use is more generally one of convenience than intentional artistic statement. Still, with the distance of time, it’s hard not to gaze into the blue and see something more than pure color staring back.

If you’re interested in viewing cyanotypes at the MHS, try exploring the Wigglesworth family photographs II, the Rotch family photographs, and the Bemis family photograph album, or heading to ABIGAIL and doing a subject search for “cyanotypes.”