By Nathan Braccio, Assistant Professor, Lesley University

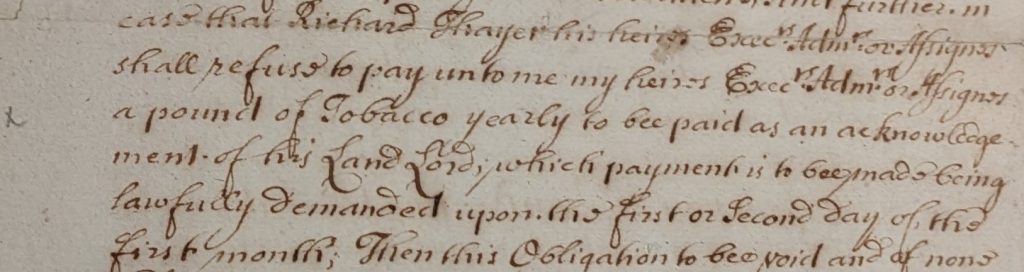

“A pound of Tobacco yearly to be paid.” Starting in 1657, for the next one-hundred years, this is what Richard Thayer and his heirs owed the Massachusetts sachem, Josiah Wompatuck. The payment was due on “the first or second day of the first month.”

These lines were neatly written within a 1657 “deed,” now part of the A.E. Roth Collection of the MHS. Strikingly, Wompatuck was not selling land, but leasing it to Thayer with a number of stipulations. While stories, many true, often present manipulative colonists as cheating Indigenous people out of their land, Wompatuck was no naive negotiator and this was not his first land deal.

Josiah Wompatuck was a sachem (leader) of the Massachusetts people. Like his predecessor Chickabut, he was an ally of the colonists and over his life gradually sold settlement rights to colonists in the area that today makes up metropolitan Boston. Today, a state park in Hingham bears his name. A man who lived within twenty miles of the heart of the English colony of Massachusetts Bay for the majority of his life and regularly negotiated with the settlers was not likely to be duped by their machinations to seize land.

Instead, in this deed and others, Wompatuck carefully worked to ensure that the document reflected a negotiation between aggressive colonial demands and the interests of his community and himself. Here, while Wompatuck did ultimately provide the colonists the land they sought for farming and settlement, he ensured that Richard Thayer produced a document acknowledging Wompatuck as his “land lord.” If Thayer, or his heirs, ever failed to pay, the lease would be “void and of none Effect.” This document, combined with the payment, created an unambiguous record of Wompatuck’s retention of political authority over the land. Sachems in New England had an established practice of collecting tribute from their people in exchange for rights to farm or hunt on land. The tribute was generally paid annually, and often in deer skins. This established a reciprocal relationship between sachem and subject, reflecting the authority of the sachem. While not paying in deer skins, Thayer’s payment of tobacco fits into this Algonquian practice of tribute. Ultimately then, Thayer in this “deed” became a subject of the sachem Wompatuck and his heirs. In Algonquain political culture, Thayer’s ability to occupy the land relied on the continuation of Wompatuck’s sovereignty.

This is not to say that Wompatuck, like so many other skilled New England Indigenous leaders, was not a victim of colonial chicanery. Both during and after his life, colonists over decades slowly and steadily took land, reneging on agreements across New England when it suited them. Still, Wompatuck and other sachems creatively resisted and found ways to navigate a rapidly changing world. Wompatuck not only convinced colonists to acknowledge his rights in English documents, he made agreements with the English that benefited his community. For example, in the 1630s, he and his predecessors established an alliance with Massachusetts Bay in a long-running struggle with Narragansett sachems. Wompatuck’s deed stands as a testament to the persistent authority and importance of Indigenous leadership in 17th century New England.