By Daniel Bottino, Rutgers University and MHS Society of Colonial Wars in Massachusetts fellow

Read an earlier post about the Secrets of the Seals at the MHS.

A notice printed in the Boston Gazette dated December 13, 1736, reads, “Lost a silver seal from a man’s watch, coat of arms on one side, CMH cypher and sloop cut into other side.”[1] Perhaps it slipped from its attachment to a watch chain during a walk or horseback ride through the city streets. We do not know if this small item was ever located or returned to its owner—it may be that it still lies where it was lost, waiting for a future archeologist to unearth it and return it to public sight.

This misplaced item, referred to as a “silver seal,” is a stamping instrument or “seal matrix” used to create an impression in wax or paper. Although thousands of colonial era New England seal impressions, usually in wax, have survived to the present day, surviving colonial seal matrices are much rarer. This makes sense, for one matrix could produce hundreds of seal impressions. Furthermore, wax seals are attached to documents—legal papers and letters—which have often been preserved for their written content. Conversely, personal seal matrices are small, as they were meant to be used by hand, and thus easily lost or destroyed over the passage of centuries. As the practice of sealing began to fall out of fashion in the 19th and 20th centuries, it is possible that many of these colonial era matrices, once carefully passed down through the generations, were discarded as useless relics of a bygone era.

Yet, to gain a full understanding of the material history of sealing in colonial New England, matrices must be studied as well as seal impressions. The collections of the MHS hold many surviving matrices—illustrated below is a matrix bearing the arms of Cotton Mather, certainly an illustrious resident of Boston. Yet this particular seal was made by silversmith Nathaniel Hurd (1730-1777) who was born after Mather’s death in 1728. Perhaps this seal was fashioned by Hurd for one of Mather’s relatives. Like the seal in the lost notice, this seal is a fine and valuable piece of jewelry, its handle made of ivory and its design carved in silver. Besides serving its basic purpose in creating seal impressions, such a precious object was likely also a status symbol and marker of wealth. After its owner’s death, a seal made skillfully of silver or gold stood a good chance of preservation as a family heirloom before, perhaps, an eventual donation to an archive or museum.

On the other hand, most colonists in New England clearly could not afford to purchase precious seals made by prominent artisans. Their humbler matrices likely were made of more common metals such as brass, their handles perhaps made of wood rather than ivory. I have not found any of these more “ordinary” seals during my research at the MHS thus far—it is likely that few, if any, have survived through the centuries, although I remain hopeful.

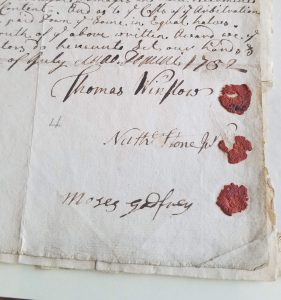

For those colonists who desired a cheaper option, their own fingers could serve as matrices. While prominent New Englanders such as Cotton Mather and John Adams almost certainly would not have wanted to forgo their finely made matrices and instead press a finger into hot wax, I have nevertheless discovered many wax fingerprint impressions in the MHS’s collections. All of these “fingerprint seals” date to the 18th century. I believe it likely that most employers of fingerprint seals were of lower social status than those sealers who used metal matrices. Confirmation of this hypothesis will require research into the identities of the hundreds of individual sealers in the documents I have encountered—I hope to complete this project in the coming months.

There is no evidence that the legal authority of fingerprint seals was ever looked down upon by colonial society. Indeed, as a seal’s primary purpose was to serve as a unique symbolic representation of its possessor, the fingerprint seal can be seen as the perfect seal. As was undoubtably understood by colonists, each person’s fingerprints are unique. Accordingly, when used as a matrix, a sealer’s finger produced an impression unique to the sealer, created not by a skilled engraver but rather by their own body. Ultimately, no matter what form they took, matrices were an integral part of the ritual of sealing in colonial New England, and a close consideration of their materiality will prove to be of great value in the historical study of colonial New England society.

[1] My thanks to James Kences for finding this notice.