By Evan McDonagh, Library Assistant

In 1889, visitors to the present location of the MHS would find themselves confronted by a most unusual sight: a fairground adorned in towering white tents and colorful flags. A decade before the Society came to 1154 Boylston Street, this corner of the Fenway neighborhood of Boston hosted Phineas Taylor Barnum’s Circus. Barnum entertained his audiences with the absurd and created spectacle out of the strange.

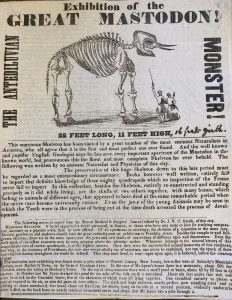

For 19th-century Bostonians, the circus represented just one means of finding entertainment in spectacle. Anything outside the norms of American life – particularly people, animals, and objects that did not conform to notions of Western civilization and classification – could be exoticized and transformed into an exhibit. In the 1800s, naturalists toured the United States and charged Americans to view their curiosities and collections. The below broadside, saved by Boston resident Ezra S. Gannett in his 1845 diary, announced the presentation of a mastodon skeleton (“the antediluvian monster!”) by “an eminent Naturalist and Physician of [Boston]” for citywide enjoyment.

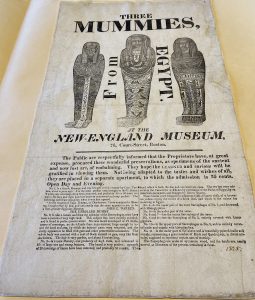

Naturalists and archaeologists similarly exhibited artifacts and items appropriated from imperialist ventures at home and overseas. The popular image of the mummy, a ubiquitous representation of Ancient Egypt and archaeology in modern times, has its roots in these 19th-century curiosity shows. In 1825, the New England Museum displayed three mummified Egyptian bodies, promising lurid sights with an additional 25 cent admission fee. Desecration accompanied exhibition as the museum removed the wrappings from these already disturbed bodies.

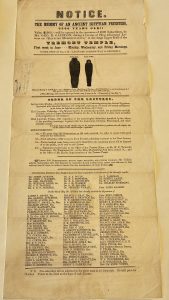

The unwrapping of a mummy could be a highly publicized affair. For instance, an 1850 event held by Boston naturalist Geo. R. Gliddon promised not only lectures on Ancient Egyptian embalming practices, but the unwrapping of a mummy before an audience and the submission of the body, wrappings, and its belongings for their inspection.

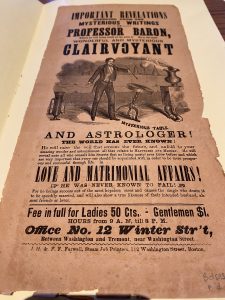

Popular fascination with absurd practices and bodies dovetailed with a growing fixation on spiritualism and the occult. Occultists like the below Professor Baron claimed access to secret knowledge and abilities beyond the pale of Western knowledge and science, often stemming from exoticized interpretations of non-Western cultures. The appeals of mysticism and otherworldly answers answered the popular appetite for spectacle.

The broadsides accompanying this blog post represent just some of curiosity shows and exhibitions that visited Massachusetts during the 19th century. They tell a story not just of contemporary entertainment, but also the commodification of those deemed absurd: prehistoric and unusual animals as well as artifacts, corpses, and beliefs of outside cultures. Part II of this blog post series will focus on people and the rendering of non-European bodies as curiosities.