By Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

The Guardian, “America’s greatest race journal,” was a Black-owned newspaper published in Boston. The paper was founded in 1901 by businessman William Monroe Trotter and librarian George Washington Forbes. The MHS collection of Garrison family papers includes one full issue of The Guardian, dated 16 December 1905, the bulk of which is dedicated to commemorating abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison on the centennial of his birth. It’s also a fascinating snapshot of Black activism during the Jim Crow era.

The Guardian offices were located first on Tremont Row, but in 1907 moved to 21 Cornhill Street, the same office from which Garrison had published his famous Liberator. Trotter idolized the abolitionist, and that certainly comes through in his flowery prose. The masthead even features a Garrison quote: “Liberty for Each, for All and Forever.” But Trotter also didn’t pull punches when it came to those he opposed: segregationists and white supremacists, of course, but also Black accommodationists like Booker T. Washington.

On the 10th and 11th of December 1905, citizens of Boston paid tribute to Garrison with ceremonies, prayers, and concerts. This 12-page issue of The Guardian includes details of these events, transcriptions of speeches, and photographs of a number of the participants. I’d like to highlight a few of them here, but I encourage you to click on this link to see the whole issue, which includes about 40 more and has been beautifully reproduced by the MHS digital team.

Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins (1859-1930) was an author, editor, and lecturer whose ancestors fought at Bunker Hill. When she spoke at Faneuil Hall, she declared, “I am a daughter of the Revolution, you do not acknowledge black daughters of the Revolution but we are going to take that right.”

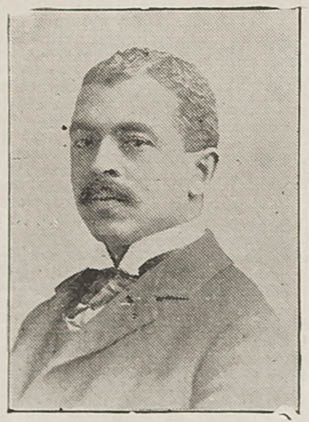

Attorney Clement Garnett Morgan (1859-1929) was the first African American to receive both an A.B. and an LL.B. from Harvard. The list of his academic honors and achievements could fill up a blog post of its own! At a speech in 1890, he declared, “I am glad to be a Negro […] I mean to be a Negro. On the bottom of my heart is written Negro.”

Nellie Brown Mitchell (1845-1924) was a classically trained singer and voice teacher who performed throughout New England, including at both Black and white churches, as well as the west and south. She performed at Garrison’s funeral in 1879 and at the centennial.

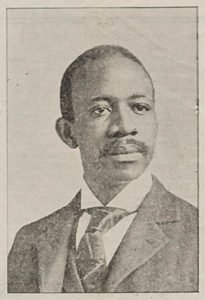

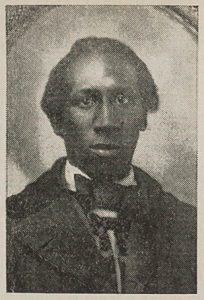

J. Nathaniel Butler had worked with William Lloyd Garrison at the Liberator. He is described as “venerable” and “aged” in 1905, so he was probably the same man who had assisted at an attempted rescue of freedom seeker Anthony Burns 51 years before.

Other photographs in the paper depict clergy, artists, military men, individuals affiliated with the Niagara Movement, and many more. Among them are Mark R. DeMortie, Wesley J. Furlong, Eliza Gardner, Byron L. Gunner, Martin L. Harvey, Reverdy C. Ransom, William L. Reed, William H. Richardson, Hannah C. Smith, and John J. Smith.

Francis Jackson Garrison (1848-1915), the youngest child of William Lloyd Garrison, delivered a rousing speech that tied racism to other societal harms, including sexism, xenophobia, imperialism, and political corruption. If his father were still alive, he said, he would not only see the wholesale disenfranchisement of African Americans, but also…

He would find Negroes excluded from juries, from all town, city and state governing bodies, denied legal intermarriage with whites, restricted to Negro galleries in the theatres and Negro cars on the trains, subjected to excessive penalties for violations of law […] He would find women denied their full political rights in all but four states of the Union, and the Chinese […] still excluded as outcasts. He would view with amazement the spectacle of the United States seizing distant lands, slaughtering their people by tens of thousands, and establishing colonial government.

For a detailed blow-by-blow of the commemorations that took place on 10-11 December 1905, see The Celebration of the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Birth of William Lloyd Garrison, published the following year.

Apart from Garrison-related material, this issue of The Guardian contains several other items of interest. For example, multiple articles relate to the resignation of John Gordon as president of Howard University. Under Gordon’s leadership, the curriculum of the school had been changed to one focusing more on “industrial education.” Students considered this change an insult to their academic abilities and protested, eventually forcing Gordon out. One protest involved as many as 400 students.

Another article rails against a vagrancy law in Macon, Ga. that would allow police to arrest any Black person they deemed to be “loitering” or “idle.” According to the article’s author, some Black men had achieved a level of relative comfort that enabled their wives not to work. Chief Conner of Macon, to help the “suffering [white] housewives […] issued orders for all idle Negro women to be rounded up, and unless they can show that they have employment they will be sent to the chain-gang, there to cook without pay and clothed in stripes.”

Finally, I’ll draw your attention to this eye-popping headline: “Negro Has Legal Rights. Court Rules He Is Entitled to Protection Under Law Against Lynching—Great Decision.” This brief bulletin refers to the case of Thomas M. Riggins v. United States. Riggins had participated in the lynching of a Black man named Horace Maples, but argued that he had committed no crime because the protections afforded by the Constitution simply did not extend to African Americans. The Supreme Court ruled against him.

The Guardian closed up shop in either 1955 or 1960 (sources differ). I hope you’ll take some time to read through this fascinating newspaper or visit the MHS to check out the rest of the Garrison family papers.