By Meg Szydlik, Visitor Services Coordinator

Trigger warning: use of outdated but period-typical language to describe disabled individuals.

As a disabled person myself, I’ve always had a particular interest in the treatment of disabled people. With that in mind, I wanted to explore what materials the MHS has regarding disability. One thing I immediately noticed was that the stories of disabled people I found in the archive are rarely told from their perspective. “Nothing about us, without us” is a slogan from the disability rights movement. Looking at these materials, it is clear why.

One group of disabled people in the archives is circus freaks. Freak shows populated by disabled people travelled around the country, providing an uncomfortable kind of entertainment in a world where disability usually meant death or concealment. Similarly named geek shows often traveled with circuses or sideshows and were equally exploitative (and something I don’t recommend looking up unless you have a strong stomach). Both types of shows were popular and traveling sideshows drew enormous crowds during the 19th and 20th centuries.

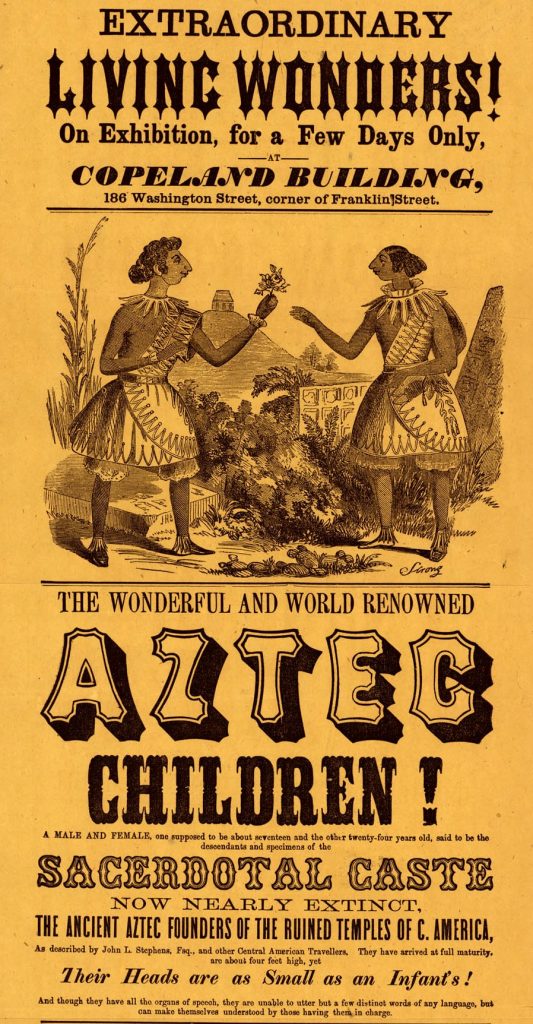

The MHS collection of broadsides includes some that feature a pair of siblings referred to as “The Aztec Children.” They are billed as one of the last remaining examples of a particular priestly “caste” in Mesoamerican culture. In reality, the siblings (Maximo and Bartola) were born into poverty in El Salvador with microcephaly, and their mother was assured that they would get treatment if she allowed them to go. There is no historical evidence that the “caste” claimed for their heritage ever existed.

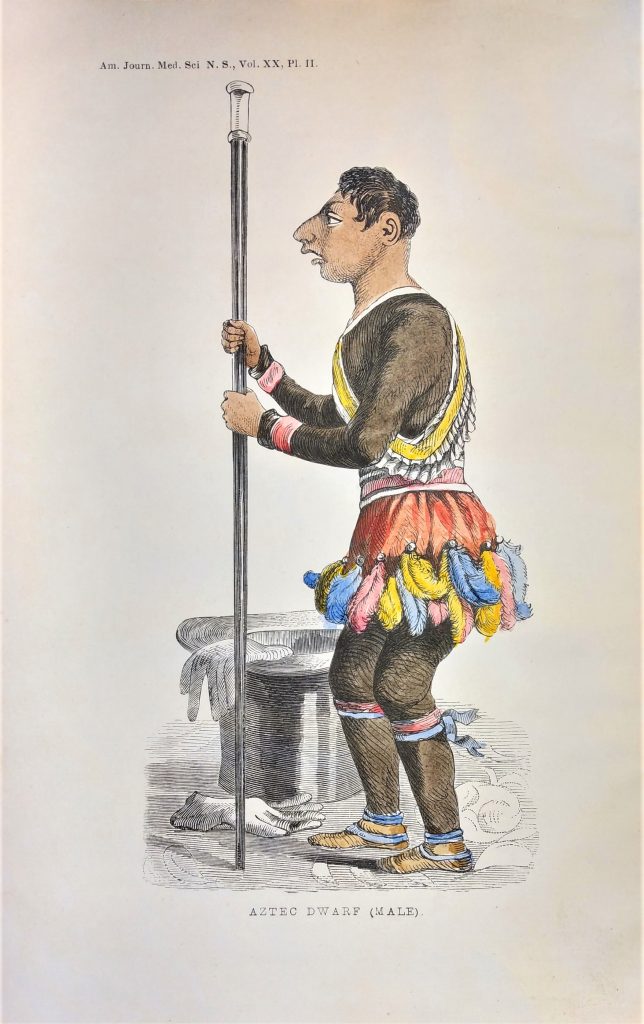

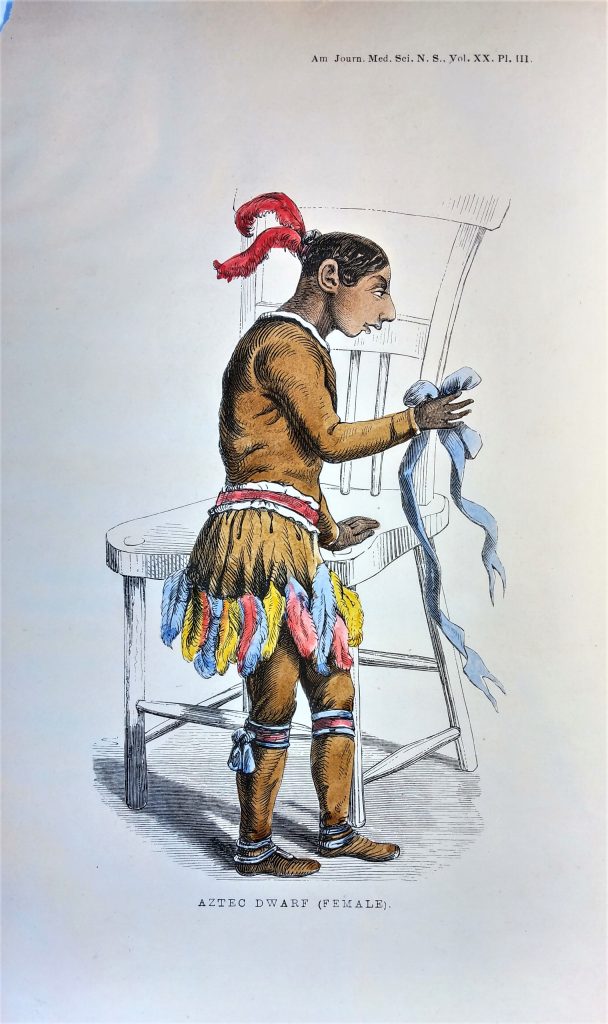

These broadsides are a window into how people in the 19th century perceived those with disabilities. The language treats them as curiosities and oddities, rather than the fully formed people they are. An article called “An account of two remarkable Indian dwarfs exhibited in Boston under the name of Aztec children” was published by the American Journal of Medical Sciences after Maximo and Bartola were examined repeatedly compares them to monkeys and comments on the shape and size of their heads as evidence of idiocy. Phrenology was rampant and the foundation for a lot of race “science” and white supremacist arguments. It’s not an accident that so many “pinheads” (circus performers with microcephaly, because of the pointed shape of their heads) were from Latin America and billed as the “missing link.”

Reading these sources left my skin crawling. The language they use to describe disabled people is deeply dehumanizing and infantilizing. The American Journal of Medical Sciences also approached their examination of the Aztec Children as though they were scientific curiosities to be analyzed rather than actual human beings. While presenting himself as neutral, the author, Jonathon Mason Warren, notes that “a question naturally arises to an observer first visiting these beings, whether they belong to the human species; and it is only after the eye becomes accustomed to their appearance that the brotherhood is acknowledged. (8)” It is impossible to remain both detached, “scientific,” and respectful of the other party’s humanity. Through it all, I never saw anything with the voice of the actual Aztec Children, or other circus performers. I know they exist, and places like Circus World share a more complete history of circuses.

On the flip side, despite how degrading it was, working as a circus freak was one of the only ways for visibly disabled people to make a living in this time. Huge numbers of disabled people lived in almshouses or were cared for at home, and experiences in those places could be brutal. At a circus, at least performers were making their own money that they could use however they wanted. When weighing a decision between starvation and degradation, it’s no wonder so many people chose to live. It’s hard to blame them for accepting the treatment they did when the Americans With Disabilities Act was still more than a century in the future, especially knowing that disability discrimination is still rampant. Yet the romanticization of these kinds of environments in movies like The Greatest Showman leaves a lot of room for a more robust look at what went into this form of entertainment.

While circus freaks are one group of disabled people in the MHS archives, they are not the only one. Next time, I will look at the way that “feeble-minded” disabled people were treated and how their experience was recorded.