By Heather Rockwood, Communications Associate

Despite being discouraged from being commercially successful, women artists in the 19th century created wonderful works of art that are important. The MHS has some great examples of such work in the collection. My focus here will be on artists who painted portraits.

Susan Anne Livingston Ridley Sedgwick’s best-known work is a portrait of someone famous, an enslaved woman who sued for her freedom and won, thereby making enslavement illegal in Massachusetts. Elizabeth “Mumbet” Freeman then worked for the family of the lawyer who helped her. She eventually bought her own home and had her portrait painted, something rare at the time. Sedgwick, the daughter-in-law of the lawyer in Freeman’s case, wrote several children’s books and also painted. This portrait of Freeman is important in several ways. First, it is of someone who in that period wouldn’t normally have had their portrait made. Second, it demonstrates the special relationship between Freeman and the Sedgwicks. Finally, besides the portrait, the MHS also holds the jewelry that Freeman is wearing in the painting, confirming she owned and wore it during her lifetime.

Caroline Negus was born into a family of painters. She exhibited paintings at the Boston Artist’s Association, the National Academy, and the Boston Athenaeum. She was most famous as a portraitist, but her botanical artwork was published in the medicinal herb book The American Vegetable Practicein 1841. Her watercolor portrait of Catherine Sargent is important to abolitionist history. Sargent, who was born and lived in Gloucester, Massachusetts, was an abolitionist and friend of William Lloyd Garrison. Negus was known to be a realistic painter, and although realism was trending at the time in the United States, she exceeded the norm in her painting of Sargent. Of note is the detail in the lace cap and collar, as well as in Sargent’s dress, especially when compared to the plain stippled background.

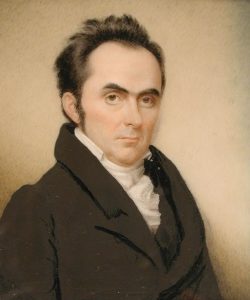

Sarah Goodridge was a distinguished and prolific portrait painter in Boston between 1820‒1850. She had high profile clients such as Daniel Webster, US Congressman, Secretary of State, and a lawyer who argued over 200 cases before the Supreme Court, and Edward Everett, US Congressman, US Senator, 15th Governor of Massachusetts, Minister to Great Britain, Secretary of State, and President of Harvard University. The portraits of Webster and Everett in the Society’s collection share the same style as the previous two in their use of the three-quarter profile and plain background. However, less attention was paid to the sitters’ clothing and more to their facial likeness and expression. These paintings demonstrate that women found opportunities to paint important subjects and have a share of commercial success.

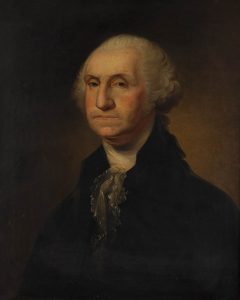

Jane Stuart’s story is a bit different, she was the daughter of Gilbert Stuart, considered to be one of America’s foremost portraitists. Jane grew up watching her father paint and helped him by grinding paints and filling in his paintings’ backgrounds. She learned to paint by watching him, and he considered her a great artist, better than he had been at her age. When Jane was 16, her father died, and she set up a studio to support her family with her artwork. Because she painted in her father’s style, most of her commissions were replicas of her father’s work, especially his painting of George Washington. The painting of Washington shown here, attributed to Jane Stuart, is held by the MHS. Throughout her career, Jane also finished many of her father’s unfinished paintings and exhibited her paintings at the Boston Athenaeum, the National Academy Museum and School, the Academy of Fine Arts, and the American Academy. Today, her paintings are collected and displayed at museums throughout the United States, not only for the importance of her subjects, but also for her talent as an artist.