By Gwen Fries, Adams Papers

Prince Saunders (or Sanders, c. 1775–1839) was an author, educator, and statesman whose work took him to Britain and Haiti. Saunders spent his early life as a teacher in New England. His words and influence provided the necessary funds to build the Abiel Smith School, the oldest public school in the United States built for the sole purpose of educating African American children and now the Boston location of the Museum of African American History.

In 1815, Saunders and Baptist minister Thomas Paul sailed for London to meet with abolitionists William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson. While on board, Saunders befriended two young men—14-year-old George Washington Adams and 11-year-old John Adams II, the two elder sons of the U.S. minister to Britain, John Quincy Adams.

A week after their arrival in London, Saunders visited his young friends. “Mr Saunders, a black man, who has been some years a Schoolmaster at Boston, and who came from America in the same vessel with my sons, called and paid me a visit this morning,” John Quincy Adams recorded in his diary on 2 June 1815.

Saunders became a frequent visitor to the Adams home throughout the following years. He regularly took the boys to church with him, and they passed intellectually inspiring evenings at his lodgings. A teacher to his marrow, Saunders took the boys—including seven-year-old Charles Francis Adams—along on many educational field trips, including to the Foundling Hospital in London and to Lt. John Clarkson’s estate in Purfleet for a meeting of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade. On 22 July 1815, John Quincy Adams recorded, “Mr Sanders came back with our three boys, very much gratified with their visit to Mr John Clarkson at Purfleet— Mr Sanders dined with us.”

Saunders often stayed for dinner, deepening his relationship with John Quincy and Louisa Catherine Adams. On 26 July 1815, Saunders came to the Adams residence in Ealing to speak to John Quincy Adams. He “asked my opinion, and advice, about his project of going to St: Domingo— The primary object is to introduce the systems of schooling according to the plans of Bell and Lancaster, into that Island— Petion has sent over here to request that some person should be sent out to his part of the Country, for that purpose— Christophe, is represented, as equally earnest for the establishment of schools within his territory.”

Adams refrained from advising Saunders, perhaps not wanting to influence any international schemes in the name of the United States government. Nevertheless, Saunders continued to socialize with the family.

On 17 April 1816, Prince Saunders took a walk with John Quincy. “I had much Conversation with him upon the subject of his visit to Hayti, as he calls it, or St: Domingo, and found he was in the highest degree delighted with his new connection there, with king Henry (Christophe) of whom he spoke in high terms of praise and admiration; but he was very reserved, with me, in speaking of his own present Mission, and of his future views.”

George, John, and Charles spent the next few days in London with Saunders. On 20 April 1816 they returned home “much gratified with their visit.” John Quincy noted that, “Mr Sanders has been much more communicative with them about his Mission to Hayti, than he was to me. He is to be ordained a Priest of the Church of England; and then to be consecrated a Bishop of Hayti, according to the rites of the Church of England. He is also to be made Duke of Cape Henry.”

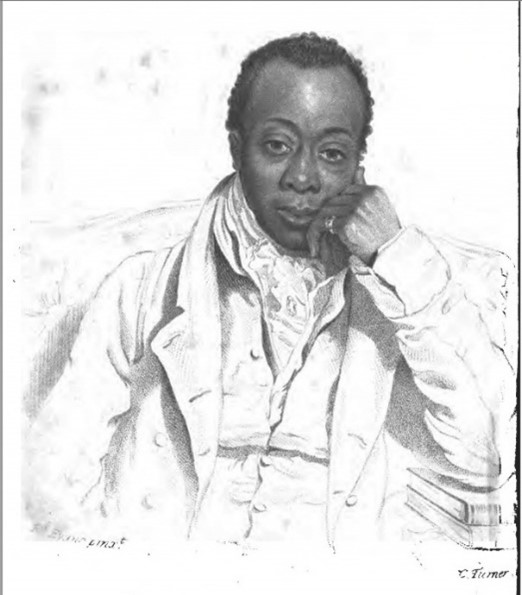

Saunders had an incredible talent for bringing together luminaries—aristocrats, abolitionists, authors, botanists, chemists, generals, politicians, professors, patrons, artists, editors, and musicians. John Quincy and Louisa Catherine were invited to several soirees at Saunders’s home on Everett Street. On 27 July 1816, the Adamses encountered “a Portrait of Mr Sanders, in a splendid fancy dress, or the Court dress of the kingdom of Hayti, hung up over the Sopha. It had been brought home from the Painters while we were at dinner.” Adams recorded in his diary that “Mr Sanders is to embark for Hayti the tenth of next Month; but is to return here again next Winter.”

Adams gave his final mention of Saunders on 13 October 1818: “On returning to my lodgings I found there Mr Prince Sanders the black man; who has returned from his establishments in the kingdom of king Henry of Haÿti. I asked him if he intended to return thither, to which he did not think proper to give a direct answer. . . . He appeared to be labouring however with the project of colonizing Hayti from the free people of colour in the United States. He admitted that the Government of King Henry was of rather an arbitrary character, and in respect to personal liberty and security was susceptible of some improvements. He spoke however very guardedly and with great reserve. I gave him my opinion of king Henry’s government very freely. Our conversation was interrupted by the arrival of the hour for my departure—”

John Quincy, Louisa, and their sons were leaving to return to the United States so that Adams could take up his appointment as Secretary of State. That interrupted conversation was to be their last. Prince Saunders spent the rest of his life traveling between England and Haiti, dying in Port-au-Prince in 1839.

The Adams Papers editorial project at the Massachusetts Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the generous support of our sponsors. Major funding for the John Quincy Adams Digital Diary was provided by the Amelia Peabody Charitable Fund, with additional contributions by Harvard University Press and a number of private donors. The Mellon Foundation in partnership with the National Historical Publications and Records Commission also supports the project through funding for the Society’s digital publishing collaborative, the Primary Source Cooperative.