By Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

Today (30 January) marks the 185th anniversary of the death of Asi-Yahola, leader of the Seminole Tribe of Florida.

Asi-Yahola (Anglicized to Osceola) is a fascinating figure with a complex biography. His name was Billy Powell when he was born in 1804 in Alabama—at that time, part of the Mississippi Territory. He and his mother were members of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, but after the Creek Wars of 1813-1814, they fled to Florida, where they became members of the Seminole Tribe. When he reached adulthood, he was given the name Asi-Yahola. He is best known as a commander of the Seminoles during what is now called the Second Seminole War.

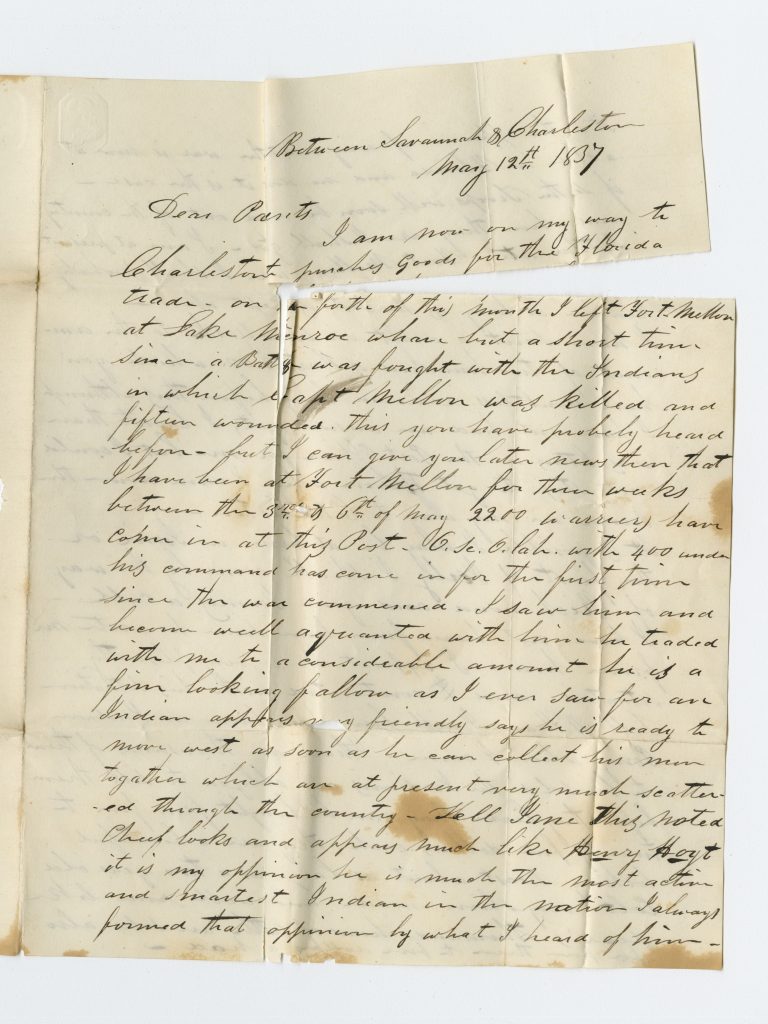

The only known reference to Asi-Yahola in our manuscript collections is a letter in the Howe-Fogg family papers written by Josiah Fogg, Jr.

In 1837, Fogg was 26 years old and working as a sutler at Fort Mellon (a.k.a. Camp Monroe) in present-day Sanford, Florida. A sutler was a civilian who sold goods to troops. Fogg left the fort on 4 May 1837 and traveled north “to purchase goods for the Florida trade.”

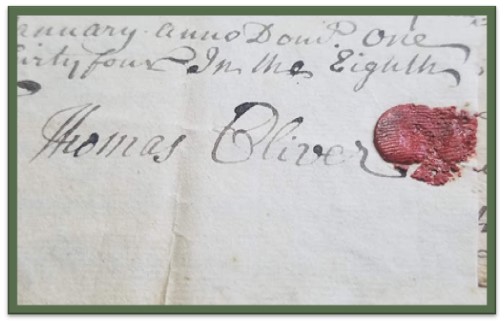

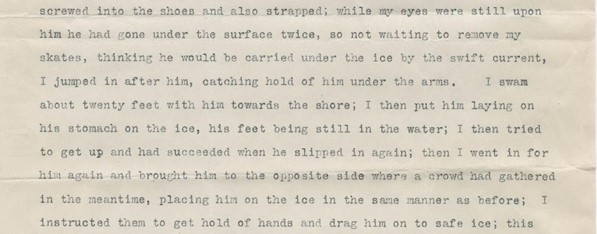

Somewhere along the route between Savannah and Charleston, on 12 May, he wrote to his parents at Deerfield, Mass. As you can see in the image above, the letter is torn and stained in several places, but Fogg’s writing is thankfully still legible. First he referenced the 8 February attack on Fort Mellon, in which “Capt Mellon was killed and fifteen wounded.” Then he name-dropped Asi-Yahola. (I’ll retain his misspellings.)

Between the 3rd & 6th of May 2200 warriers have come in at this Post [Fort Mellon]. O-Se-O-lah, with 400 under his command has come in for the first time since the war commenced. I saw him and became well aquainted with him. He traded with me to a considerable amount. He is a fine looking fallow as I ever saw for an Indian appears very friendly says he is ready to move west as soon as he can collect his men togather which are at present very much scattered through the country. […] It is my oppinion he is much the most active and smartest Indian in the nation. I always formed that oppinion by what I heard of him.

I found further context in The Book of the Indians, by Samuel G. Drake (1845), and The Indian Wars of the United States, by Edward S. Ellis (1892). Asi-Yahola had, in fact, brought his warriors to the fort at the beginning of May. According to Ellis:

The Indians professed their desire to make peace, and, during the month of May, there were assembled more than 3000 men, women, and children at Fort Mellon, Lake Monroe, to whom a thousand rations were issued. The chiefs came and went as they pleased, and it did begin to look as if the war was about over, for Osceola had slept in the tent of Colonel Harney. General Jesup was confident that the disgraceful conflict was closed, and the Indians would keep their pledge of departing without further opposition. (p. 269)

Fogg certainly thought the war was nearly over; “no doubt it is the case,” he wrote his parents. But while a minority of Seminole chiefs had consented, under certain conditions, to be removed west of the Mississippi River, Asi-Yahola decidedly had not. When Gen. Thomas Jesup started preparing to forcibly transport the Seminoles gathered at Fort Mellon, Asi-Yahola retreated with his people back into the woods.

Unfortunately, it wasn’t long before he found himself in the hands of the U.S. government anyway. On 21 October 1837, just a few months after he met Fogg, Asi-Yahola was captured under a flag of truce outside St. Augustine, Florida. The man responsible was none other than Gen. Jesup. He’d flouted the rules of engagement, and the Seminoles were outraged, but there wasn’t much they could do; Jesup had the support of the U.S. government.

After a short imprisonment at Fort Marion, Asi-Yahola was moved to Fort Moultrie outside Charleston, S.C., where he died of illness on 30 January 1838. He was (probably) 33 years old. He is buried on the grounds of Fort Moultrie.

Several towns, counties, and natural landmarks bear Asi-Yahola’s name, and commemorative statues and plaques have been erected in his honor. One statue in Silver Springs, Florida portrays him plunging his knife into a treaty, a depiction which has great symbolic resonance, but which may also, according to historian Donald L. Fixico, be literal.