By Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

Today (2 November) would be the 288th birthday of Daniel Boone. According to the theme song of the 1960s television show, he was the “rippin’est, roarin’est, fightin’est man the frontier ever knew.”

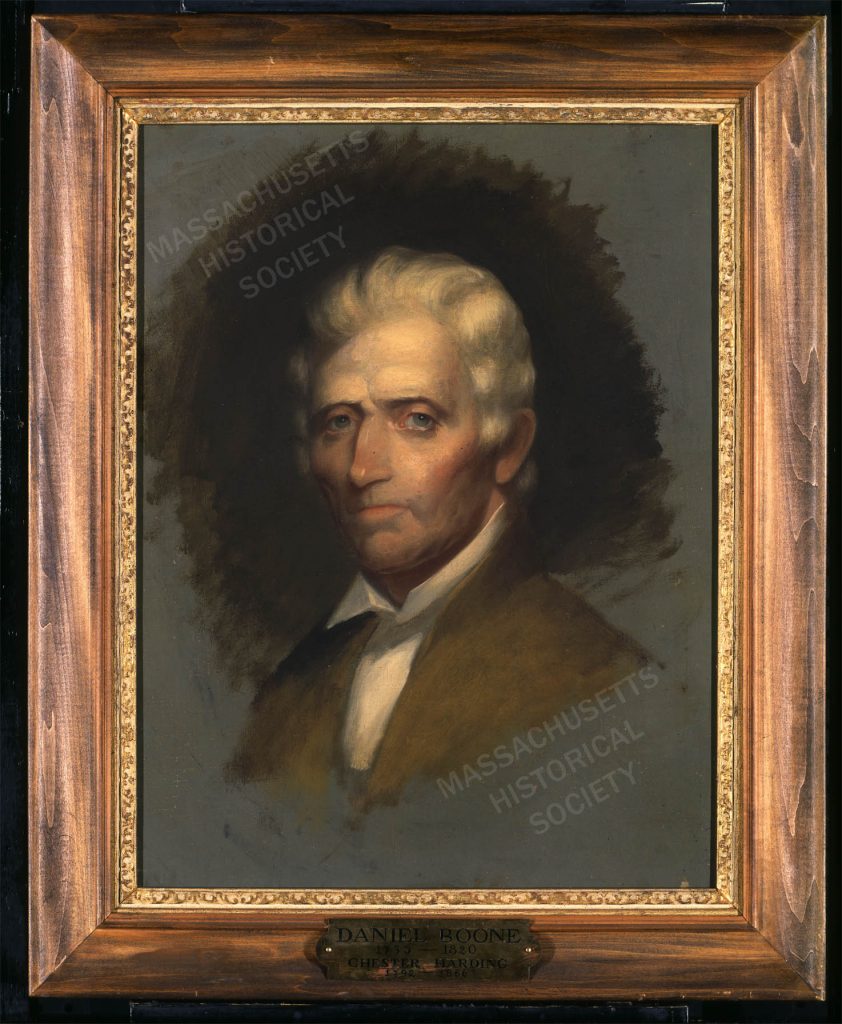

What does Daniel Boone have to do with the Massachusetts Historical Society, you ask? Well, the MHS holds the only known portrait of Daniel Boone painted directly from the subject himself.

The story of how this portrait came to be sounds like the premise for a movie. In 1820, Chester Harding was a 20-something self-taught journeyman portrait painter living in St. Louis, Missouri. He’d been raised in a large family in Massachusetts and upstate New York and had known real financial hardship, as described in his autobiography My Egotistigraphy. He’d tried his hand at various trades and, almost by chance, learned he had a gift for portrait painting. Thus began what would become a long and illustrious career.

Daniel Boone, on the other hand, was 85 years old and quite literally nearing the end of his life. He was a folk legend even in his own time, a frontiersman, surveyor, veteran of the French and Indian War and the American Revolution, and leader in the white colonization of Indigenous lands in Kentucky. I won’t attempt to dissect Boone’s problematic legacy with Indigenous and enslaved people (he himself was an enslaver); that is being done by others much more qualified. But in 1820, his fame was probably unparalleled.

You wouldn’t have known that, though, from Chester Harding’s description of his first meeting with Boone. The painter, in his autobiography (pp. 35-6), gives us a brief look into the notorious frontiersman’s unassuming retirement.

In June of this year [1820], I made a trip of one hundred miles for the purpose of painting the portrait of old Colonel Daniel Boone. I had much trouble in finding him. He was living, some miles from the main road, in one of the cabins of an old block-house, which was built for the protection of the settlers against the incursions of the Indians. I found that the nearer I got to his dwelling, the less was known of him. When within two miles of his house, I asked a man to tell me where Colonel Boone lived. He said he did not know any such man. “Why, yes, you do,” said his wife. “It is that white-headed old man who lives on the bottom, near the river.” […]

I found the object of my search engaged in cooking his dinner. He was lying in his bunk, near the fire, and had a long strip of venison wound around his ramrod, and was busy turning it before a brisk blaze, and using salt and pepper to season his meat. I at once told him the object of my visit. I found that he hardly knew what I meant. I explained the matter to him, and he agreed to sit. He was ninety [sic] years old, and rather infirm; his memory of passing events was much impaired, yet he would amuse me every day by his anecdotes of his earlier life. I asked him one day, just after his description of one of his long hunts, if he never got lost, having no compass. “No,” said he, “I can’t say as ever I was lost, but I was bewildered once for three days.”

He was much astonished at seeing the likeness. He had a very large progeny; one grand-daughter had eighteen children, all at home near the old man’s cabin: they were even more astonished at the picture than was the old man himself.

Daniel Boone died just a short while later, on 26 September 1820. To me, this portrait is an artifact of what must have been a series of fascinating meetings between one man at the beginning of his career and another at the end of his.

Harding made a few replicas of the painting, but Leah Lipton, in her very helpful 1984 article in The American Art Journal, shows that the portrait here at the MHS is the unfinished original painted from Boone himself. Harding gave or sold the painting to George Tyler Bigelow, chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, who donated it to the MHS in 1861.

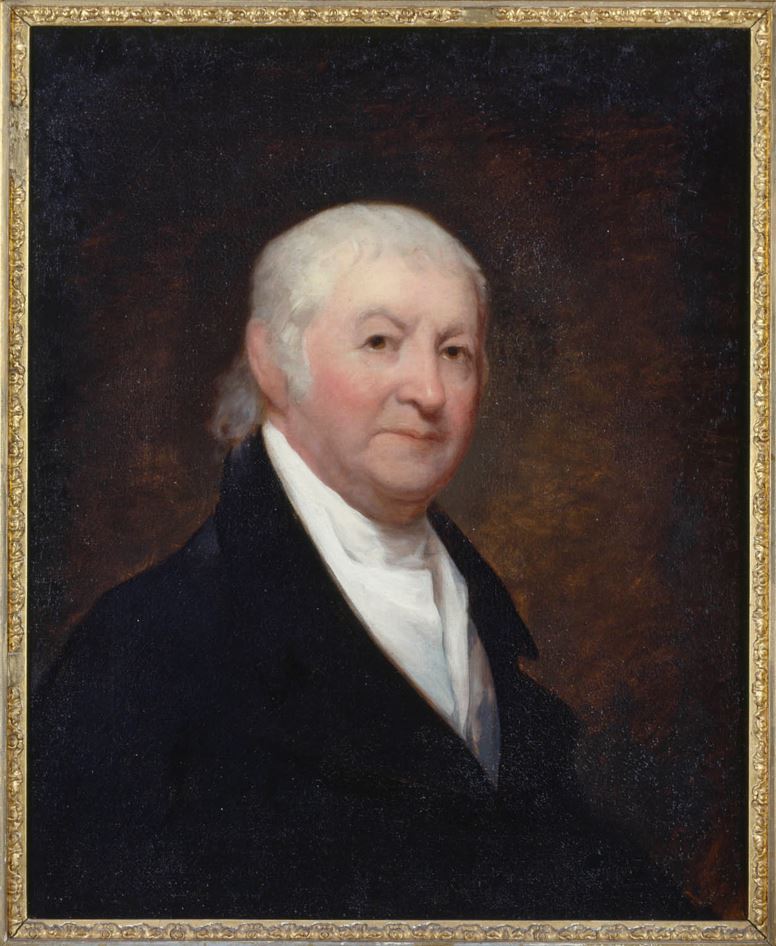

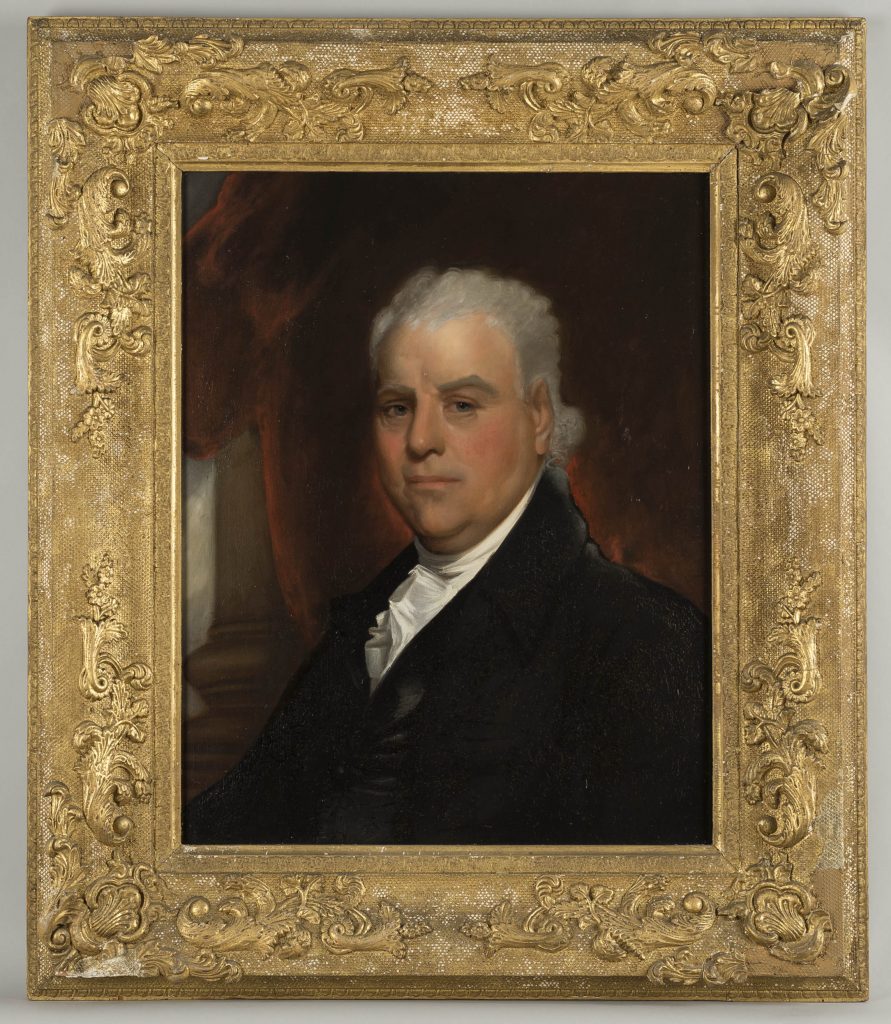

The MHS holds a number of other portraits painted by Chester Harding, including the following.

We hope you’ll stop by and see them in person!