By Dr. Jaimie Crumley, 2022-2023 Research Fellow at Old North Illuminated, University of Utah

The Massachusetts Historical Society maintains and preserves the extensive records of Christ Church in the City of Boston, an active Protestant Episcopal Church. [1] Christ Church, founded in 1723, is known as the Old North Church. Located in Boston’s North End, Old North is the city’s oldest standing church building. In the colonial period, Old North received moral and financial support from members of King’s Chapel, New England’s first Anglican parish,[2] and the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG). The SPG was a London-based group founded by the Church of England to proselytize the Atlantic World.[3]

In addition to being home to an active congregation, Old North is a bustling historic site on Boston’s freedom trail. Old North joins other historic sites in Massachusetts and beyond that have turned to archival records to remember and confront their complicated past. Many of Old North’s visitors come to learn more about Paul Revere’s 1775 midnight ride. In April of 1775, Revere asked his friends, Old North’s sexton Robert Newman and vestryman Captain John Pulling, to hang signal lanterns in the church’s steeple. Through the lantern signals, they alerted their neighbors that the British troops were approaching “by sea” (across the Charles River) and not by land.[4] Revere’s midnight ride and Old North’s role in it inspire our imaginations. However, a laser focus on that night often leads us to overlook the church’s contributions to histories of race, slavery, sexuality, economics, and religious life throughout the Atlantic World.

Old North’s storied past includes Indigenous Americans and people of African descent in Massachusetts and elsewhere in the Atlantic World. Without their displacement and unpaid labor, the church building would not exist. For example, the church’s wardens and vestry gifted the “Bay Pew” to a group of logwood merchants from Honduras for their exclusive use whenever they attended Old North. The pew signaled the church’s gratitude for the merchants’ generous gifts to the church. By accepting the logwood for decades, Old North entangled itself with the crises of unfree labor and colonial violence that plague(d) the Atlantic World. [5]

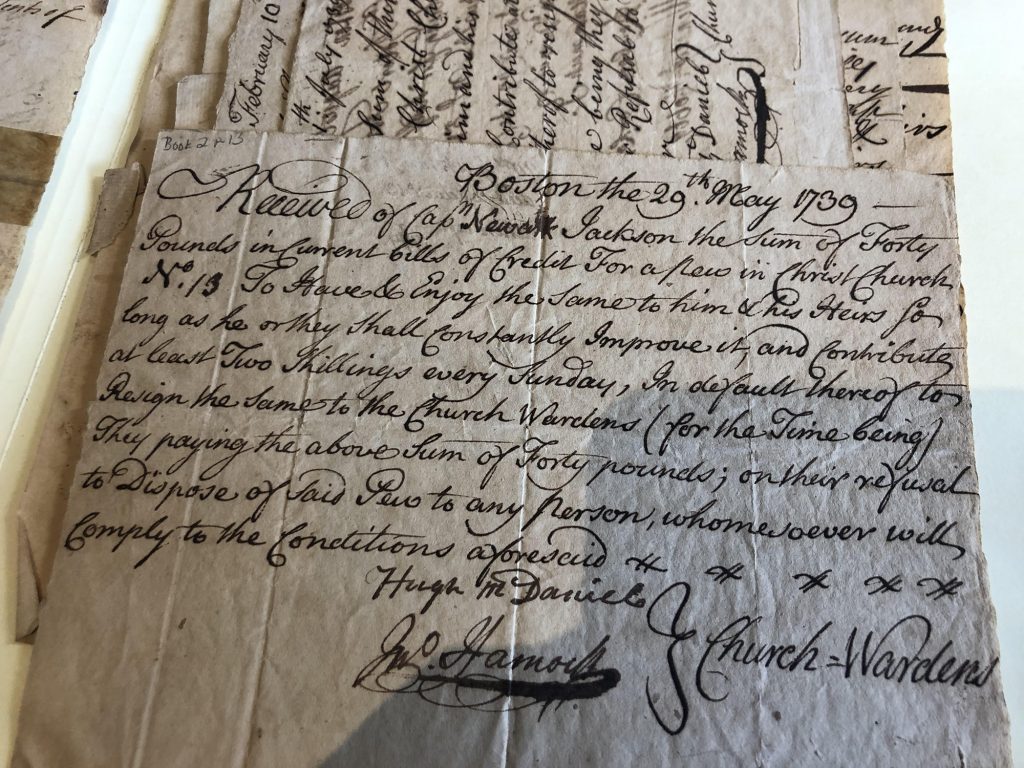

Pew ownership was commonplace in 18th and 19th-century churches. So long as they paid their pew taxes, proprietors and their families had exclusive use of their pew(s). Not everyone who held a pew deed at Old North attended the church, but their proprietorship allowed them to hold leadership roles and participate in church governance.[6] Like other colonial churches in New England, Old North was racially integrated, but seating was segregated by race, age, and social class. Thus, pew ownership in New England often mirrored each town’s geography of unfreedom and entrenched that social geography as both natural and godly.[7]

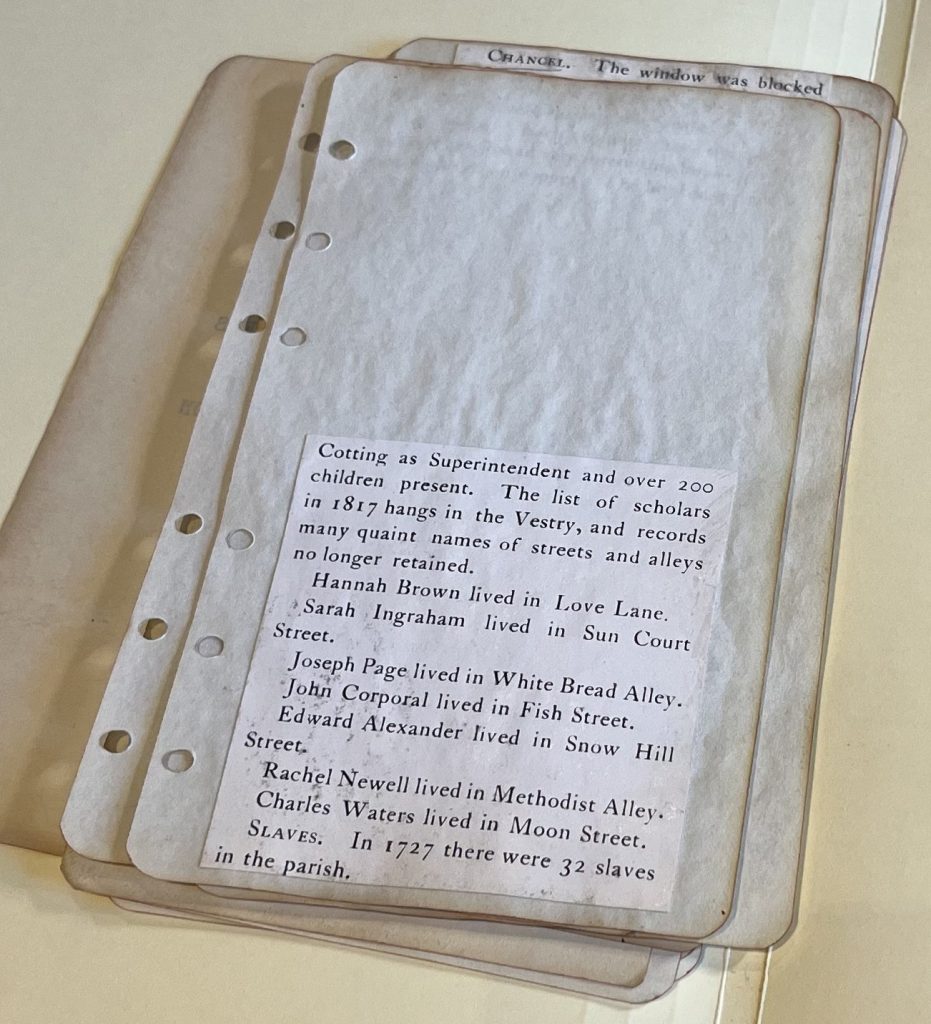

However, pews were likely a minor concern for Old North’s Black and Indigenous parishioners. In Box 20, Folder 24, of the Old North Church records, there is a historical record that was typed in 1933. The brief index covers topics including how the church attained its bells, the gifts King George II gave the church, and how the congregation formed its Sunday School.[8] One line of the index states, “SLAVES: In 1727, there were 32 slaves in the parish.”[9] The typist gleaned this information from a 1727 letter that Timothy Cutler, Old North’s first minister, wrote to the SPG’s secretary. Among other information about Old North, Cutler reported that “Negro & Indian Slaves belonging to my parish are about 32.”[10] What were the experiences of those 32 souls whom Cutler called “slaves?”

Cutler’s use of the word “slaves” as a general descriptor for his Black and Indigenous parishioners offers a stark reminder of Boston’s role in slavery and settler colonialism in the United States and throughout the Atlantic World. His word choice in a letter to the SPG secretary indicates that the British Empire believed that Black and Indigenous people naturally constituted a social and economic underclass. The growth of the Anglican Church in the Americas depended upon racial capitalism.

Old North Church celebrates its 300th anniversary in 2023. Old North’s story parallels that of the American nation-state. In 1775, lantern signals shown from Old North’s steeple lit the way for a people longing for freedom from what they called British tyranny. The story of the lantern signals offers hope to a nation and world that has experienced many dark moments. However, Old North has also participated in settler colonialism, slavery, and racism. Nearly 250 years after the signal lanterns shone from the church steeple, we turn those lights within to examine our history anew.

As Old North’s Research Fellow, my work attends to the lives of the Black and Indigenous peoples who have connected by choice or by force to the church during its 300-year history. Centering Black and Indigenous people’s stories in the history of the British Atlantic World does not undo past harm. However, their stories remind us of our shared humanity and the urgency of making historical memory more inclusive. By cultivating an inclusive approach to historical memory, we create the building blocks of safer futures for Black and Indigenous peoples.

[1] According to the collection description, these holdings consist of 52 boxes, 75 cased volumes, 6 oversize boxes, and 12 record cartons. The records span the years from 1685-1997.

[2] See “Laus Deo Boston, New England, The 2nd September 1722.,” September 2, 1722, Old North Church Records, Box 1, Folder 7, Massachusetts Historical Society. The records of King’s Chapel are here. A list of other collections of King’s Chapel records is in the “Related Materials” section.

[3] In 1754, Old North’s first rector, Timothy Cutler, preached at an SPG gathering. His sermon is in Box 24, Folder 27.

[4] One of Paul Revere’s written accounts of his April 18, 1775 ride is in Box 46, Folder 1.

[5] Ross A. Newton, “‘Good and Kind Benefactors’: British Logwood Merchants and Boston’s Christ Church,” Early American Studies 11, no. 1 (2013): 15–36.

[6] The so-called “Smithett Controversy” in 1854 and the church conflict of 1882 revealed the pitfalls of connecting authority in the church to pew ownership. See Boxes 23 and 24 of the Old North Church records.

[7] See the pew deeds from 1724-1945 in Box 19 and Volumes 41, 42, 43, and 44 of the Old North Church records.

[8] Old North’s Sunday School was established in 1815. It was the first to be established in the region. Although the church was facing financial challenges in the nineteenth century, its members maintained a commitment to being charitable by providing education and clothing to the neighborhood’s children.

[9] “Clerk’s Book/List of Pew Owners, 1933,” Old North Church Records, Box 20, Folder 24, Massachusetts Historical Society.

[10] Francis Lister Hawks and William Stevens Perry, eds., “Dr. Cutler to the Secretary,” in Historical Collections Relating to the American Colonial Church, vol. 3, 1727.