By Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

When you think of archivists at work, you probably picture us buried under piles of dusty documents filled with stuffy prose and inscrutable handwriting. Well, sometimes we are. But you may be surprised how often I laugh out loud at something I find in one of our collections. Case in point: the diary of Amy Lee Colt.

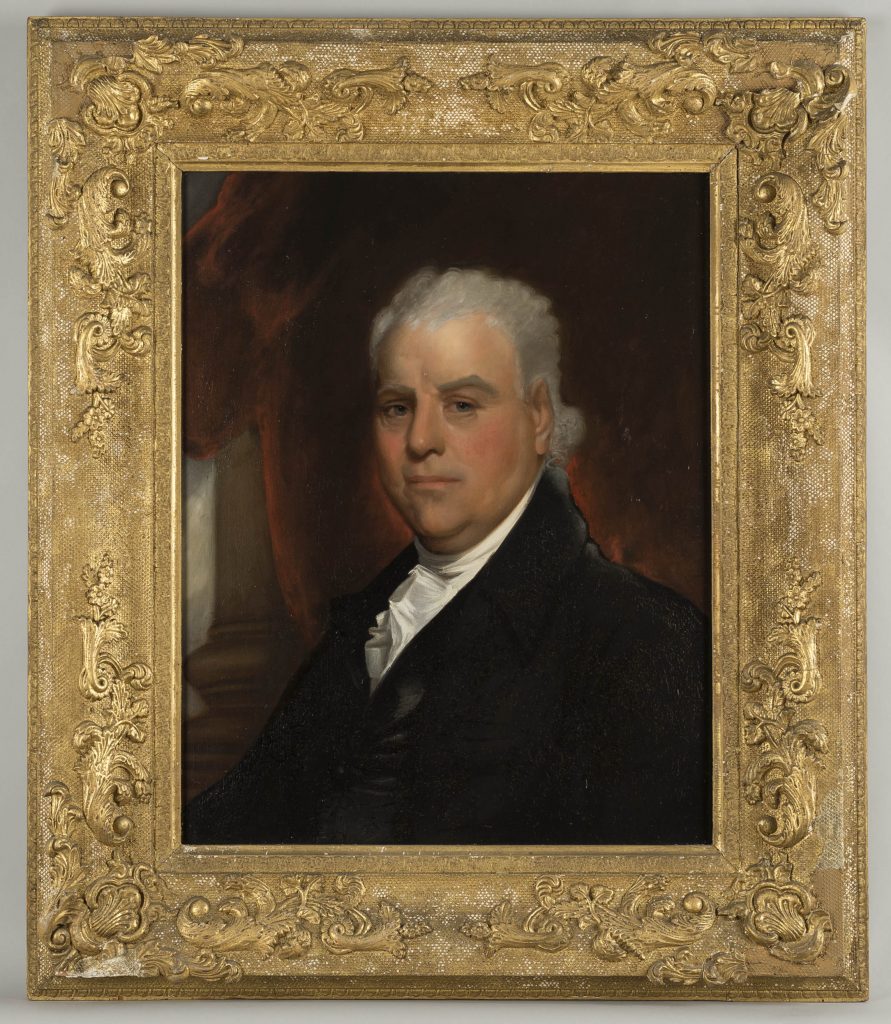

Amy Lee was the youngest child of social worker, author, and philanthropist Joseph Lee of Boston, Brookline, and Cohasset, Mass. Her mother, Margaret Copley (Cabot) Lee, was a teacher who founded kindergartens in Chestnut Hill and the Back Bay and served as a director of the Associated Charities of Boston. According to Joseph’s biographical sketch of Margaret, as well as public records, Amy was born on 9 April 1903, although her grave marker bears the date 8 April 1902.

Amy’s diary is part of a collection of her father’s papers here at the MHS. The volume is really more of a combination diary and commonplace-book, with diary entries, original poetry, random thoughts, quotations, lists, and prayers. Unfortunately the entries aren’t dated, but based on internal clues, we can estimate that it was probably kept between 1918 and 1925. Amy was apparently a teenager when she began it and wrote her last entry shortly after the birth of her first child.

The volume begins with this inscription:

Dear little book to thee I impart

The secrets of my beating heart

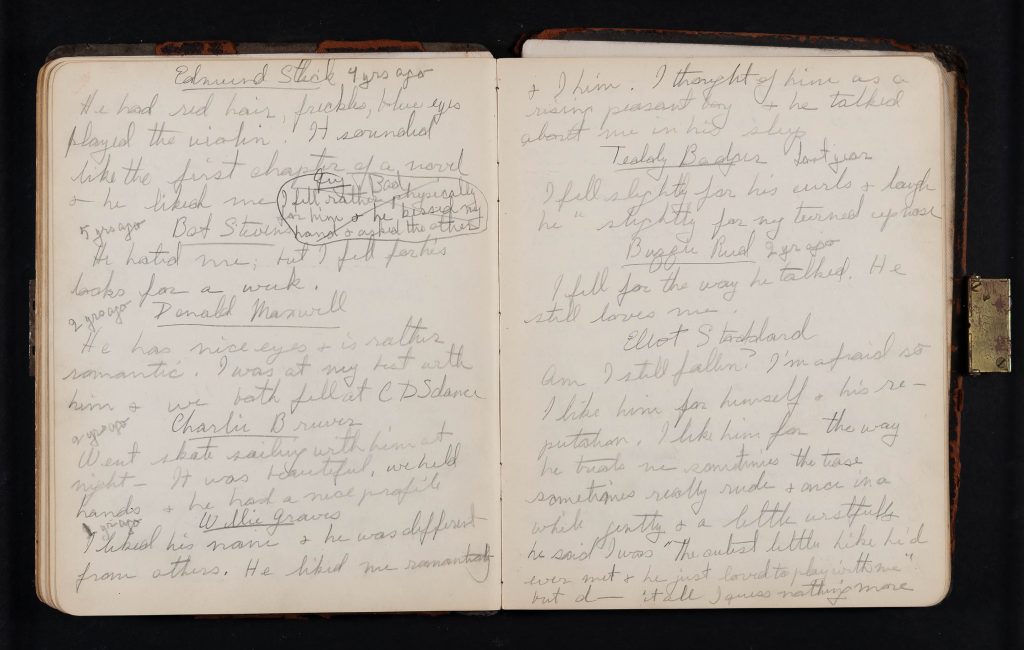

And if it’s secrets of a beating heart you’re looking for, you will not be disappointed. I knew I was in for a treat when I saw a page with the heading: “Boys I have partially fallen fore [sic] in the past.”

Amy not only listed the boys by name, but included a brief commentary on each. She was incredibly funny and had a real knack for description, conveying a lot of information in just a few words. Here are some of my favorites:

“Tad is charming & unique. He puts you on a pedestal & as theirs [sic] not room for two falls off.”

Edmund “had red hair, freckles, blue eyes[,] played the violin. It sounded like the first chapter of a novel & he liked me.”

“I fell rather physically for [Guy] & he kissed my hand & asked the other.” (This entry is crossed out with the word “Bad” written over it.)

Bat Stevens “hated me; but I fell for his looks for a week.”

“I liked [Willie Graves’s] name & he was different from others. He liked me romantically & I him. I thought of him as a rising peasant boy & he talked about me in his sleep.”

All of these boys, however, paled in comparison to the “devilishly handsome & fascinating” Elliot Stoddard. “Great guns when will I see him again? He’s some boy,” Amy wrote. Her most frequent and fulsome descriptions are those of Elliot.

Am I still fallen? I’m afraid so[.] I like him for himself & his reputation. […] I shall never forget the time he bandaged my arm. He was as gentle as the most skilled doctor & as careful as mother. My stomach turned cart wheels, electricity ran all over my body & I could hardly keep from vomitting [sic].

She went on to recount in great detail an idyllic and bittersweet fourth of July watching fireworks with him.

He said he was a little deaf so I had to talk near him. It just occurred to me he might have been lying. I’ve grown blasé & disgusting. I used to be unconscious & trustful. I think he liked me that night. He asked me to come & set fake fire to a barn with him at night – alone – smoking. I said I would; but I didn’t.

I think what I like best about the diary is its organization—or more accurately, its lack of organization. More than your typical diary, arranged by date with prescribed, lined spaces for entries, this volume feels like an organic outpouring of Amy’s feelings, captured in real time in all their messiness. She crossed out passages, skipped pages, and omitted punctuation marks. She composed poems to her mother, narrated adventures with friends, and speculated on religious subjects. On one page she gushed, unable to contain herself:

I’m so excited & am crazie about so many boys & life is just so perfect that I shake like an aspirin leaf with the goo goos. My ears point in the wrong direction & I’m dying of joy.

And just a short while later, she was heartbroken. Under the heading “One Gone,” she lamented the engagement of Elliot Stoddard, “the most honest, straight forward lump of fascination I ever met. […] I must not think about him.”

It took some doing, but I finally found Elliot via print and online genealogical sources. He was born in 1899, the oldest child of Ella (Tilden) and Alexander E. Stoddard. He married Mary E. Coughlin of Charlestown, Mass. on 31 October 1920.

I’d like to tell you a little more about Amy Lee Colt in my next post, so I hope you’ll join me back here at the Beehive.