By Meg Szydlik, Visitor Services Coordinator

Happy October and spooky season! I have always had an interest in the weird and wonderful and of course the MHS is full of those. However, one significant missing piece in the collection, to my thinking at least, is material regarding aliens and extra-terrestrial sightings. Most of the content that the MHS has related to the word “alien” is about the Alien and Sedition acts, passed in 1798 and signed into law by Pres. John Adams. In light of this, I decided to look at what similarities and differences the word “alien” had in 1798 compared to how it is used today.

In 1798, the word alien in the context of the Alien and Sedition Acts meant someone “foreign” to the new United States but the word was not without negative connotations. While the word had other meanings at the time as well, they are all derived from the same sense of othering and otherness. Alien was not a bland, neutral word then and it certainly is not now.

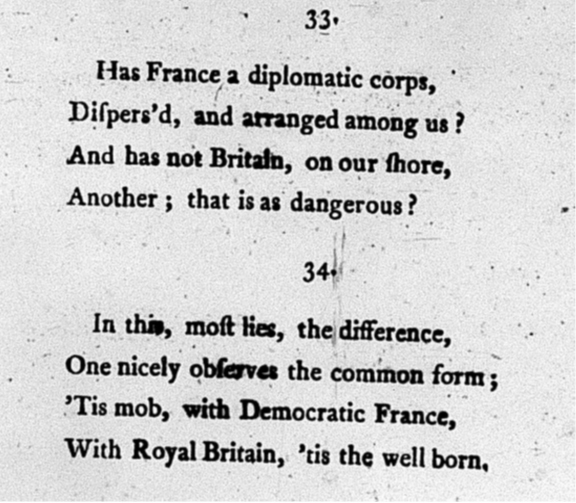

While the prevailing viewpoint today is that the Alien and Sedition Acts were unconstitutional, at the time that was a hotly contested debate. Objectors argued that because they were unconstitutional, the states were not under obligation to follow the laws, a state’s rights argument that definitely would not cause problems in the future. But despite its detractors, there was a lot of support for the laws. One such supporter was Kentucky Senator, Humphrey Marshall, who wrote a poem (below) praising the laws and waxing, well, poetic about the dangers of these non-WASP immigrants and mob rule as opposed to royal rule. Ironic, given that the United States had just gotten rid of a monarchy! His support of this, and other unpopular Federalist policies, was the end of his senatorial career.

“Aliens: A Patriotic Poem” by Humphry Marshall.

(33) Has France a diplomatic corps,

Dispers’d, and arranged among us?

And has not Britain, on our shore,

Another; that is as dangerous?

(34)

In this, most lies, the difference,

One nicely observes the common form;

‘Tis mob, with Democratic France,

With Royal Britain, ‘tis well born

We can trace many words that we use today back to that same use of the word. Words like “alienated” or terminology like “illegal aliens” (over “undocumented immigrants”) all come from that Middle English origin of alean or alyen, meaning foreign. It is not until the 20th century that the word alien was used to mean “extra-terrestrial” and even longer before it conjures up the image of creepy humanoids you see when you search “alien” today.

In my experience, modern reactions to the word alien often include images of flying saucers and characters from a sci-fi film, not the Democratic-Republicans of 1798. People claim to have had encounters with extra-terrestrial aliens and lived to tell the tale, creating an interesting tension between the 18th century use of the word and the modern one. For my part, I see this shift as making the word even more dehumanizing than it already was. After all, the group I most often use it for are foreigners of the highest degree- not only not American, but not even from Earth! It’s the ultimate foreigners. If I had to guess, the Alien Acts of 1798 probably would have ranked at extra-terrestrial aliens as even lower and less worthy of rights than the Earthlings the Federalists were so nervous about.

I also wanted to share some interesting Boston connections to extra-terrestrial aliens. One website collects people’s stories of alleged alien and UFO sightings and includes a few in the same area as the MHS, including a very close encounter. Interestingly, the North End is packed with sightings, significantly more than any other area of the city. Perhaps you have a guess as to why extra-terrestrial life seems to be such a fan of that area. Regardless, it is clear that aliens of all kinds continue to capture our attention.