By Brian Maxson, Professor of History and Editor of Renaissance Quarterly

The little-studied 19th-century benefactors Robert Cassie (1812-1893) and Anna Waterston (1812-1899) bequeathed dozens of unpublished European manuscripts, rare incunabula, and early printed books to the MHS around the turn of the 20th century. Although each of these texts holds its own fascinating history for scholars of medieval, Renaissance, and early modern Europe, these dust-covered relics of the Waterston bibliophiles also hold the keys to an untold story in American identity, race, and history. It is a story with far-reaching implications even to this day.

During the late 1800s and 1900s historians in the United States created a narrative about the history of their country. The United States, in the narrative, became a key part of the triumph of “the West.” The story went that, after the fall of Rome, centuries of despair wracked Europe. Then, the Italian Renaissance revived all that was good about Ancient Societies. Italians passed those ideas onto English Protestants who then carried them over to the original thirteen American colonies. For decades historians of Renaissance Italy have problematized those conceptions of their period while American historians have sought to create more inclusive narratives of the American past. Nevertheless, most people, including specialists, take for granted that the Italian Renaissance played some role in American history.

Yet, that idea only dates to the later part of the 1800s. In the decades before that, most American writers possessed too many Catholic and Italian prejudices to see them as key parts in a western macro narrative. Instead, some historians explicitly stated that history began during the Protestant Reformations. Some thinkers acknowledged that Protestant writers drew upon earlier Italian examples, but they did so with as little emphasis as possible. Before the establishment of the narrative of Western Civilization, Italy was deeply problematic: The art and influence could be prized, but at the same time it was a Catholic, Mediterranean country.

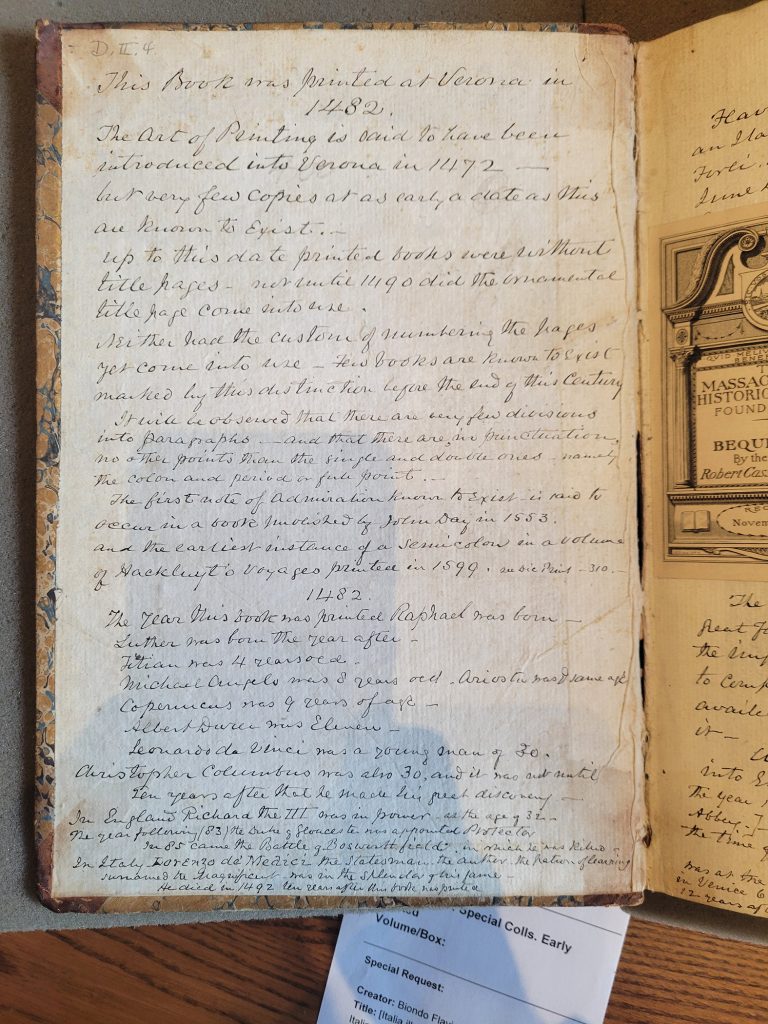

It was in that context that Anna and Robert Waterston were buying texts created or about Italian and European history prior to 1600. The Waterstons were well-connected members of New England’s educated elite. In many of their collectibles the Waterstons filled the inside covers with short essays. These essays pertained to the antiquity of the item rather than its actual contents. For example, the Waterstons’ owned a copy of Italy Illustrated¸ a work written by the fifteenth-century Italian Biondo Flavio, published in 1482. In that case, Robert covered part of the inside cover with a history of printing in the late 15th century. He noted that his book, like all printed books of the time, lacked a title page, page numbers or many paragraph indentations. Robert then turned the essay to the book’s context in 1482. After a short list of famous figures and their ages in that year (“Titian was 4 years old.”, “Copernicus was 9 years of age.” etc.), Waterston resituated his entirely Italian book into a new context: “In England, Richard III was in power as the age of 32. The year following (83) the Duke of Gloucester was appointed Protector. In 85 came the Battle of Bosworth field, in which he was killed.” Only the Italian Lorenzo de’ Medici (“the Magnificent”) warranted a mention amidst so many other historical figures. Next, Waterston penned a half page biography of Biondo Flavio before again returning to Lorenzo de’ Medici and Lorenzo’s supposed whole-hearted embrace of print. The page concluded, however, again by returning to the English context: “William Caxton who introduced the Art of Printing into England had been at work there for 8 years…”

Through repeated short essays like these the Waterstons addressed the tension between period perceptions of Italy. Their texts left the Italian context for fanciful, fictional connections with Protestant and English heroes. Eventually, Americans solved the Italian problem by arguing for the pivotal role of the Italian Renaissance as transmitter of Antiquity to the modern age. Before that, the Waterstons tended to think about their Italian books in other, usually English contexts. Through that action the books became artifacts of a time before history: Not parts of a grand narrative, but curiosities from before the narrative began.