By Heather Rockwood, Communications Associate

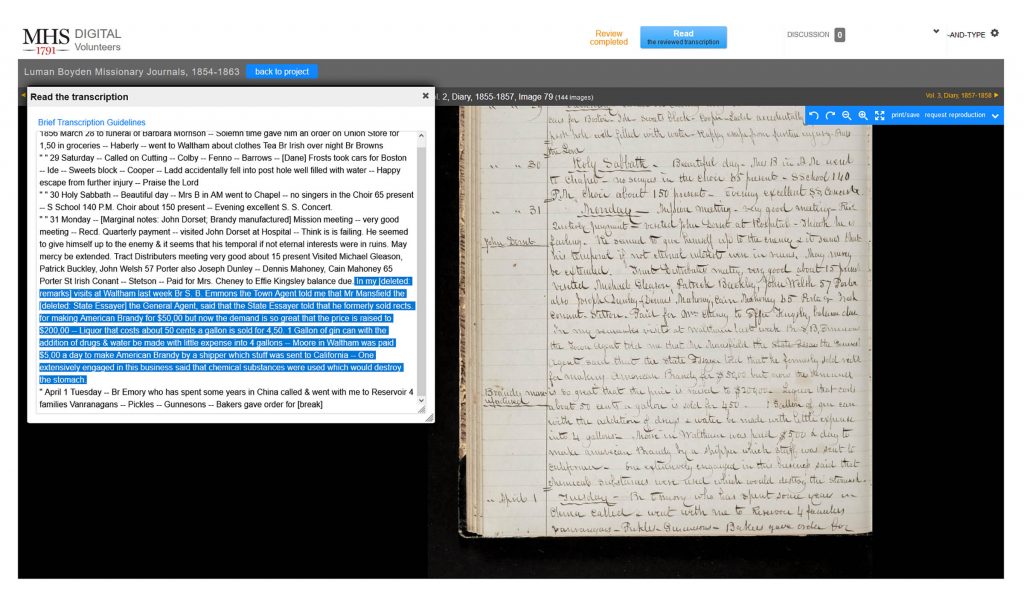

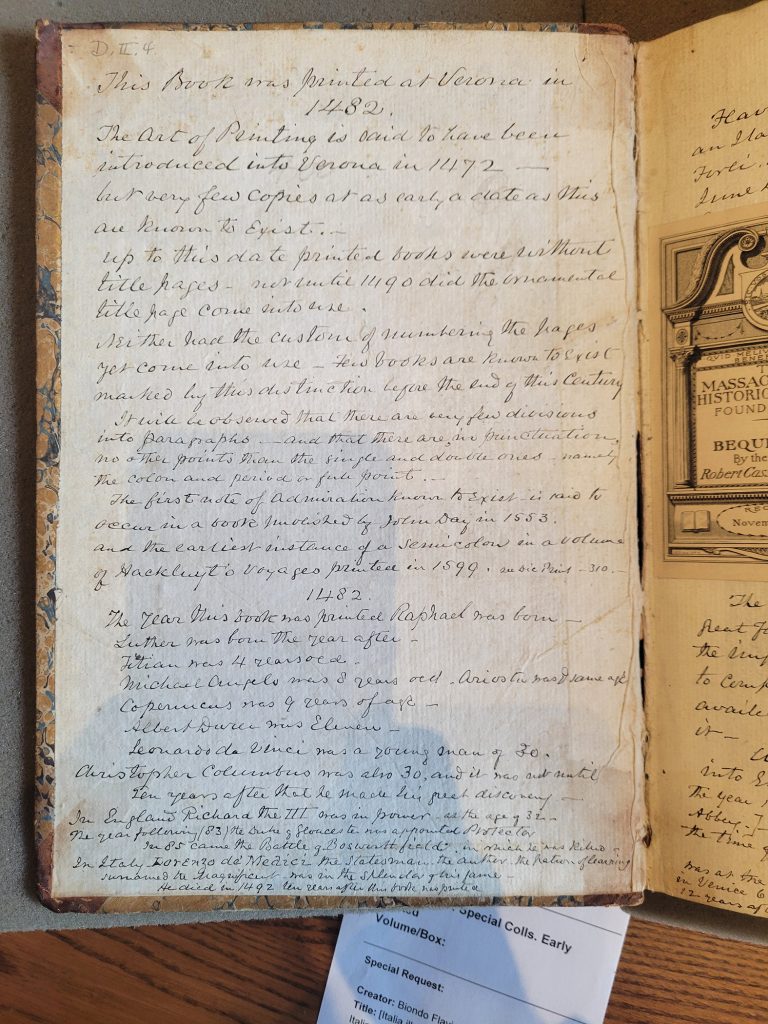

Every week I spend time reading MHS’s online archives to find quotes, images, and interesting stories for the Society’s social media and e-newsletter. I have gained a general knowledge of US and colonial history that has helped me interpret letters, diary entries and other materials found in archives. At times I’ve become momentarily horrified by what I’m reading, either because I don’t know the background of the author, or the style of writing is confusing. I’d like to share one of my “archival horrors” and my delight with its outcome with you this Halloween. The letter begins emotionally:

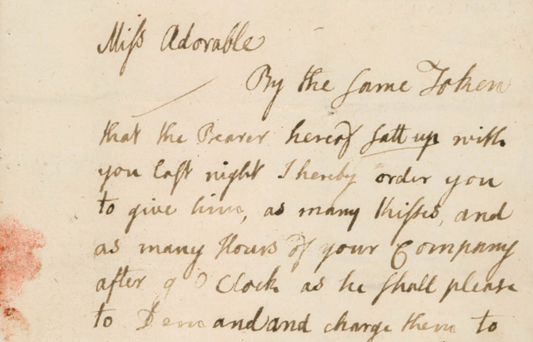

Dear Sir,

I Rec’d yours dated July the 21 &c., at the opening of which, I was not a little suprized; to see your sweet Name, affixed at the bottom of the Lines, wrote to me; to tell the truth, I could hardly Keep in my jumping heart, for it skipped like Lambs upon little Hills, but when I cam to understand the weight and solidity of the same, the wings of my Enthusiastick flame dropt off, and I was then so calm and sedate, that I could read with tears in my Eyes for desire of seeing the author of it and the weighty matter of them &c.

Letter from Israel Cheever to Robert Treat Paine, 11 July 1749

Cheever addresses Paine in a loving manner which was normal for his time—men wrote to each other using sweet language intended to convey loving, loyal friendship. But in this letter, the message begins to sound, well, a little…sexy‒ “have not the fashonable People of the world to converse with, nor no sweet Chum to confabulate with upon a Bed of Ease…” True, Cheever could mean no opportunity for a relaxed time together at a club, where cultured and privileged men of the era went to socialize with each other. Before that suggestive passage, he also notes he is in “eremo subobscura” (hidden in the forest), meaning Wrentham, Mass. where he had moved recently for a job.

The next line made me think I was reading a letter between lovers: “But I cant help letting you Know one thing, and that is I have no bosom friends in the Night upon my Lodgings. You may give a very good guesse at wt. I mean.” The line that followed dispelled my suspicions: “But for fear you should be put to trouble (Bed buggs).” I was hopeful for possibly discovering a love letter, and was disappointed when it was not.

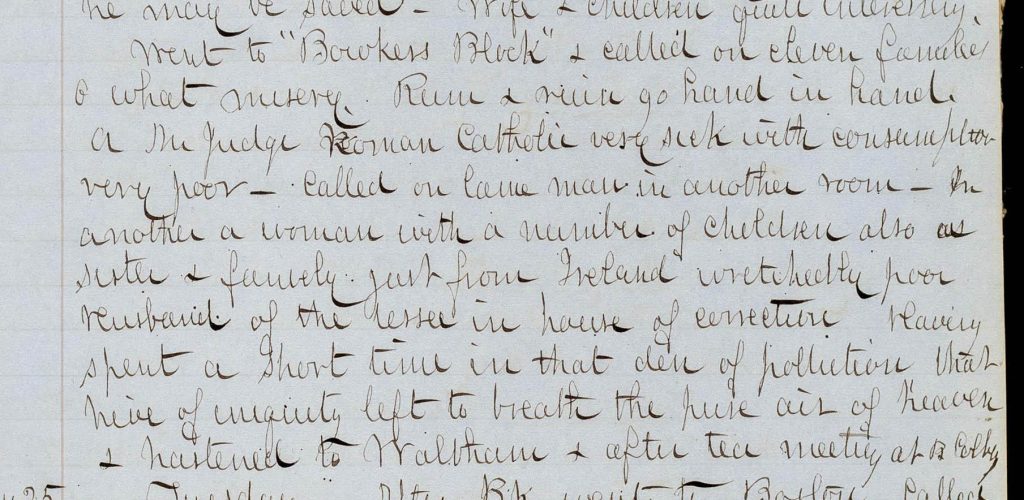

The previous lines are not the horror that I promised at the beginning. Here is where my horror started to grow. Cheever writes:

And as for my Brood, they are like to grow, by feeding of them with tender meat. In Number I have had thirty seven, but I have constantly but about 17. How many more are a coming out of the Eggshels I know not, some of these have not yet got them off their Backs.

Several thoughts came to me at once—what did Cheever do for a living? Raise livestock or chickens? If not, had I missed mention of his having children? And so many—37?! And why only 17 of them constantly with him?! And why would the children have eggshells on their backs?

Luckily, the letter’s digital transcription has notes at the end it, making my horror short-lived. The notes indicate that Cheever had taken a teaching position in Wrentham, explaining, to my relief, that his “brood” wasn’t animals or his own offspring but his students! As it was July, many of these students probably worked on their family’s farms, reducing attendance at school. The eggshell comments probably means that he thinks many of his students are very young for the classroom and does not want to guess at how many more students he will later teach.

If you were startled with a bit of horror as I was upon first reading this letter, I hope you’ve enjoyed how it turned out. Happy Halloween!