By Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

I just finished cataloging a very fun diary describing two road trips through Massachusetts, New York, and Connecticut. And not just any road trips, but road trips undertaken during the earliest days of automobile travel. This diary was written in September and October of 1906, just 21 years after the first gas-powered automobile was invented by Karl Benz and a full two years before Henry Ford’s Model T.

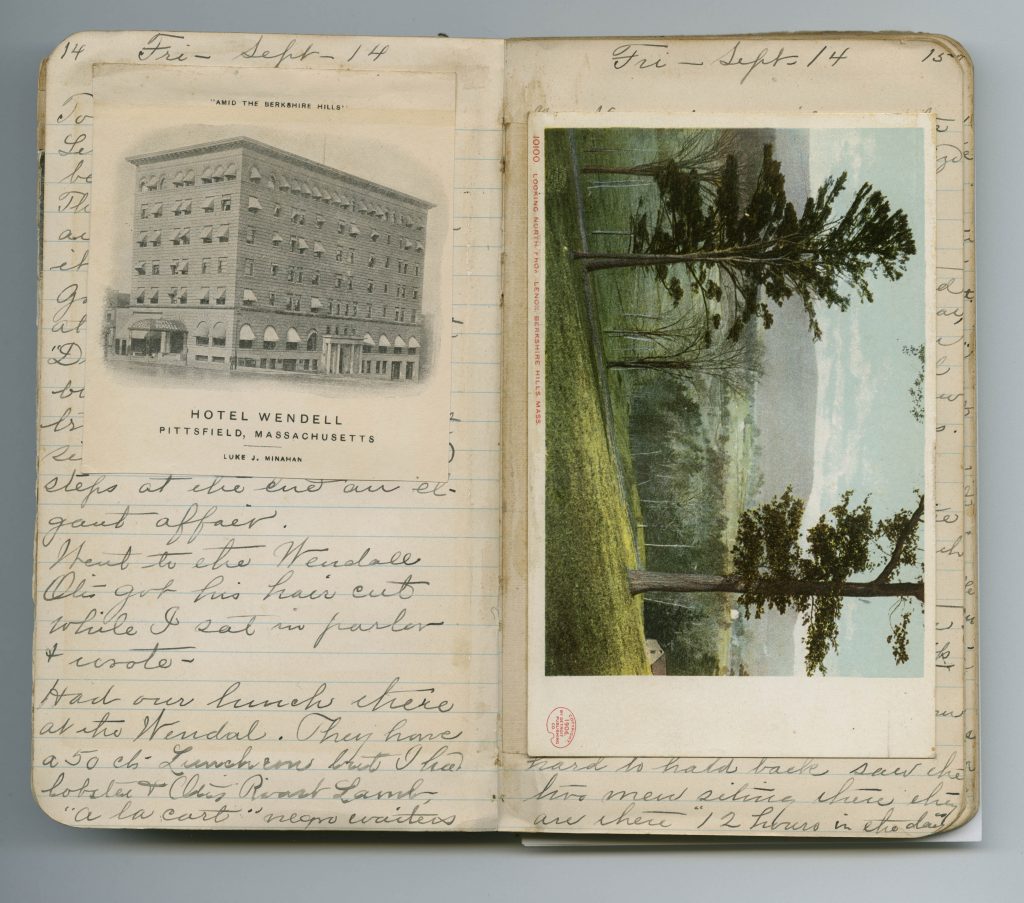

The writer is unidentified, but she and her husband were clearly driving enthusiasts, or “autoists,” in her parlance. They were constantly on the move, and their trips took them primarily through central and western Massachusetts, but also as far as West Point, N.Y. The diary describes the sights and the people they encountered along the way, as well as the hotels they stayed in and the meals they ate.

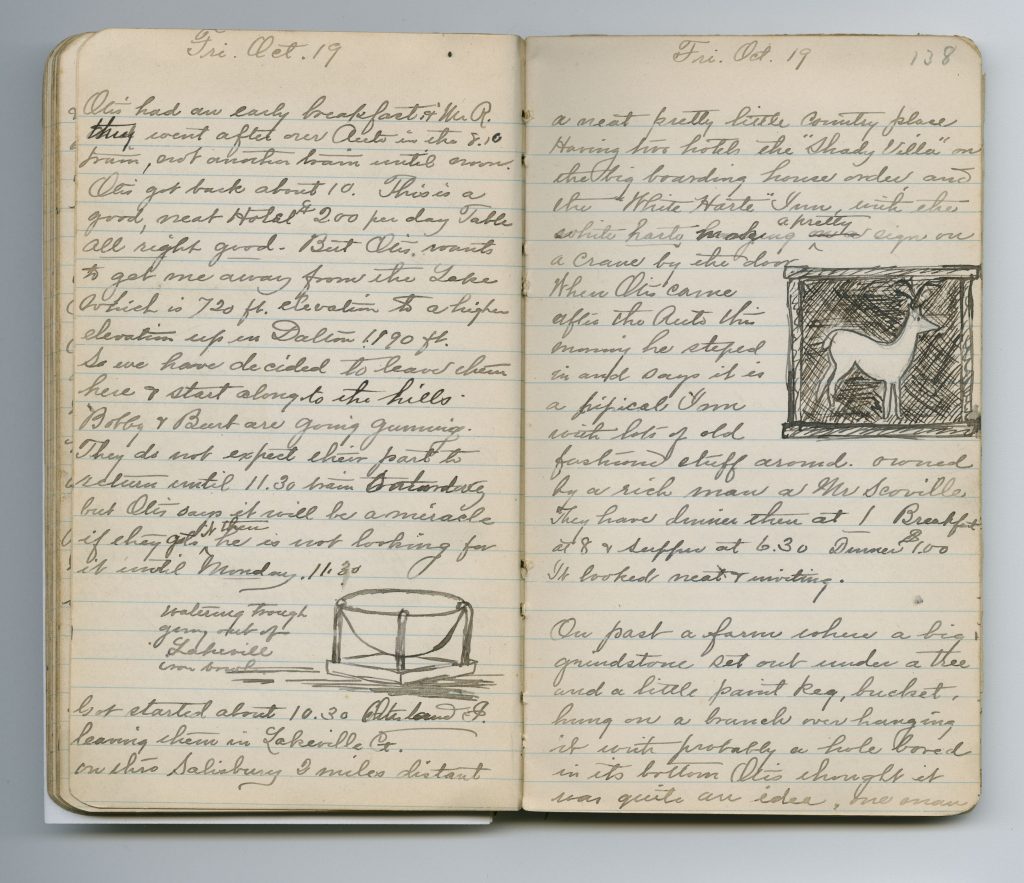

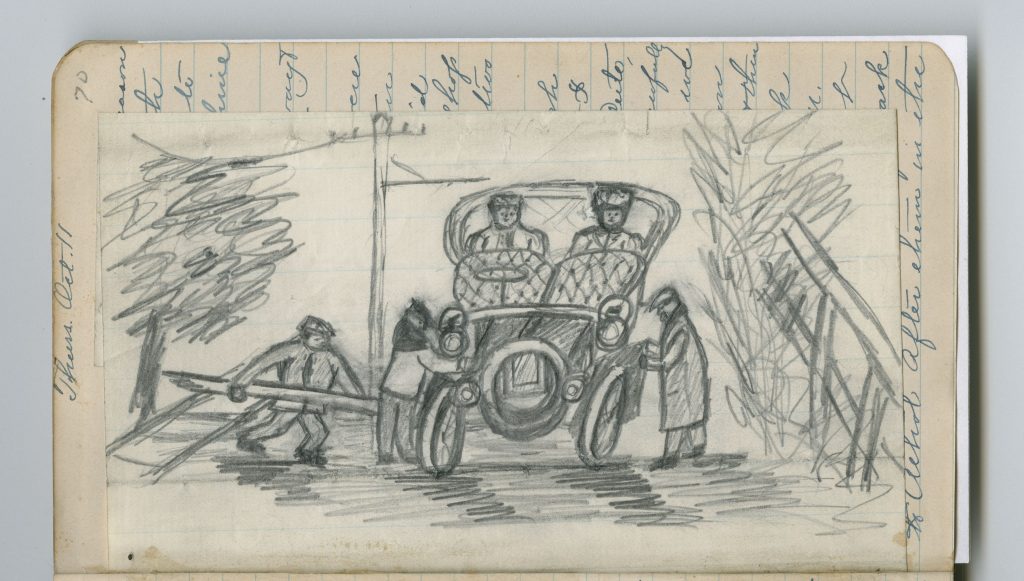

The volume is actually a combination diary and scrapbook, and pasted into its pages are a number of postcards, pieces of hotel letterhead, menus, and other printed matter. Our writer even provided some of her own illustrations.

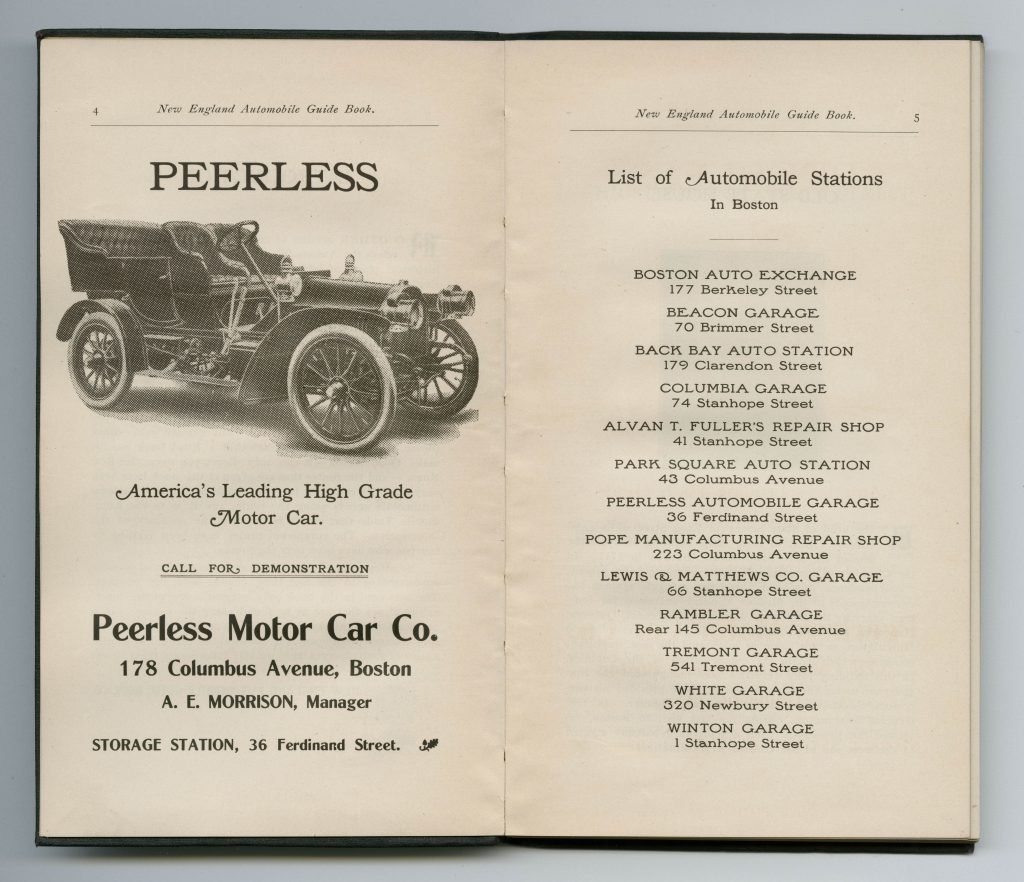

I went looking through the MHS catalog for some other sources on early automobiles, and I was not disappointed. I found The New England Automobile Guide Book, published in 1905, which describes different driving routes through the region and the sights along them. Here’s an excerpt from the introduction:

No other section of country on the Atlantic Coast offers the Automobile Tourists so many natural and historical places of interest as are to be found in Old New England. Through the mountain sections the roads are necessarily hilly, but the Motor Car that is up-to-date does not stop at the hill that has not been too steep for the horse drawn vehicle, and as every hill has its valley the beauty and grandeur of the view that is to be had from the summit, more than repays the effort of the climb.

The book also includes state traffic laws related to speed limits, safety, licensing, and registration; early advertisements for cars, some of which could be had for the low-low price of $500; and a helpful list of the thirteen garages in Boston.

The MHS also holds the photographs of the Country Club Car Company, which manufactured cars during the first decade of the 20th century. This one is definitely my favorite.

I tried to identify the diary’s author, but unfortunately was unsuccessful. She just didn’t give me enough personal information. I know her husband’s name (Otis) and the names of a few of her correspondents: Cy (Cyrus?), Josie (Josephine?), Mrs. Fisher, etc. But her relationship to these correspondents is unclear. I couldn’t even be sure what town she lived in, which might have helped to narrow my search.

However, I did identify some of her traveling companions. She took her second trip with Charles Lowell Ridgway of Winthrop, Mass., his wife Harriet (née Cross), their son Herbert Newell Ridgway, and his wife Madeline (née Clarke). Charles and Herbert were father-and-son inventors and developers of amusement parks, including Revere Beach. Rounding out the group was the Ridgways’ chauffeur Robert L. Parquett.

There are a lot of interesting details in the diary. For example, one of the things that struck me was how much DIY was involved in early automobiling. It seems that, for the most part, drivers had to maintain their own cars, as shown in this illustration.

Also, it’s obvious that cars were quite a novelty, and the diary describes scenes of children running alongside the road as they went by or crowding around to stare. According to Department of Energy statistics, in 1906, only 1.27 out of every 1,000 people in the U.S. owned cars. If my calculations are correct, that’s only about 108,520 people in the entire country.

If cars were in their infancy, so were speed limits. Our diarist was amused by an “unusual” sign in Millbrook, N.Y. prohibiting the operation of any car, motorcycle, bicycle, or horse over 10 miles an hour. She also sat in on the trial of a fellow autoist accused of traveling at an unacceptable 12 miles an hour. (He was caught by two police officers who had used stopwatches to time him.)

The hotels situated along these early driving routes ran the gamut. Some were pretty swanky, others less so. One man warned “Mrs. Otis” and her husband against the Hinsdale Hotel in Hinsdale, Mass. because “they serve nothing to eat there but plenty to drink, he never goes in there, because he’s ashamed to be seen coming out. It’s a ‘Speak Easy’ place he said, what ever that is.”

They also decided against the Quaboag House in West Warren, Mass., which “looked neat enough but there were all Irish names on the register written in pencil & only 2 or 3 a day. He thinks it may be a rum hole.”

For all her squeamishness about alcohol, however, when she came down with a bad cold, she complained:

I cant get warm, am taking the quinine, but have used up all my whiskey[.] Otis went off to the Drug store to get me some, but they would not give it to him, without a Doctor’s prescription[,] evidently thought his story about a sick wife, was a “put up job” & they were not to be fooled in that way. I want the whiskey, what am I to do.

We hope you’ll drop by the MHS library and take a look at the diary for yourself!