By Karen N. Barzilay, The Adams Papers

“There has perhaps not been another individual of the human race of whose daily existence from early childhood to four score years has been noted down with his own hand so minutely as mine.”

Diary, 31 October 1846

Five years ago, I joined a team of transcribers, editors, and digital production specialists preparing the diaries of John Quincy Adams for online publication. At the time, high quality scans of each manuscript page of the diary were available through the Massachusetts Historical Society’s website, but without transcriptions, they were only date, not keyword searchable. Our goal was to provide verified transcriptions of the diary free to the public, complete with headnotes and other features, to benefit students, scholars, and other users interested in the Adams family specifically and the Early Republic more generally.

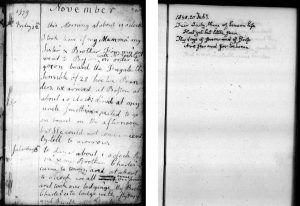

Producing a digital edition of this diary has been no small task. John Quincy Adams started keeping a journal in 1779 at age 12 and wrote almost continuously for the rest of his long life, nearly up until his death in early 1848 at age 80. There are 51 volumes of diary entries—a total of over 15,000 manuscript pages. Today, transcriptions of nearly 12,000 of those pages are available online, covering the years 1789 to 1848. On our website, you can view the original manuscript page images and transcriptions side by side. They are fully searchable and we hope people will spread the word about this helpful digital resource.

The John Quincy Adams Digital Diary is truly a collaborative project; my primary role has been to verify the transcriptions, which involves carefully comparing each manuscript page of the diary with a typed transcript for accuracy. This process is performed twice, by two different editors, to ensure that the final version you find online is as faithful as possible to the original. As with the Adams Papers printed editions, we strive to produce authoritative versions of these manuscripts for general use. It is detail-oriented work and can be tedious, but historians are nosy and always looking for an excuse to read old diaries and letters.

My dissertation was on the First Continental Congress of 1774, so for many years John Quincy Adams existed in my mind only as a little boy, the son of John Adams who was left behind in Massachusetts when his father departed for Philadelphia and who watched the Battle of Bunker Hill from Penn’s Hill in Braintree alongside his mother, Abigail Adams. During my work on the Adams Family Correspondence series back in the 2000s, the project was publishing documents from the 1790s, when John Quincy was a young, single lawyer in Boston eager to make a name for himself.

During my time working on the John Quincy Adams Digital Diary, I have had the opportunity to follow John Quincy through the rest of his extraordinary life, from his years as a diplomat in Europe to his service as secretary of state, from his presidency through his long tenure in the House of Representatives. It was painful to read about his heartbreaking personal losses, including the deaths of his parents, whom he dearly loved, all of his siblings, three of his four children, and two cherished grandchildren. It was rather dull, to be honest, when John Quincy became obsessed with various countries’ standard weights and measures in the 1810s and when he described at length the varieties of trees he planted in his garden in the 1830s. Recently, I’ll confess that it was with some sadness that I verified the transcriptions of the diary written in 1847 and 1848, just before John Quincy’s death, most of which were dictated by John Quincy and penned by another granddaughter, Louisa, due to his unsteady hand.

John Quincy Adams encountered a staggering array of familiar historical and literary figures during his life and he knew personally many of the people we associate with both the American Revolution and the Civil War. He had dinner with George Washington in 1794, shortly after Washington appointed him minister to the Netherlands, and he served briefly in Congress with future president of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis, and with Abraham Lincoln, who was on the committee that made arrangements for Adams’s funeral. Along the way John Quincy heard Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Phi Beta Kappa poem at Harvard, had lunch with Charles Dickens, and interacted with thousands of other more “ordinary” men and women of diverse backgrounds. The diary is a who’s who of late 18th-century and early 19th-century America and a window into the many political, cultural, and technological changes transforming the young nation during that period. Fortunately for us, John Quincy was self-disciplined when it came to his daily “journalizing” and his diary has survived the passage of time.

Work on the John Quincy Adams Digital Diary continues. We invite you to explore the site and follow our progress.

The Adams Papers editorial project at the Massachusetts Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the generous support of our sponsors. Major funding for the John Quincy Adams Digital Diary was provided by the Amelia Peabody Charitable Fund, with additional contributions by Harvard University Press and a number of private donors. The Mellon Foundation in partnership with the National Historical Publications and Records Commission also supports the project through funding for the Society’s digital publishing collaborative, the Primary Source Cooperative.