By Jenna Colozza, Library Assistant

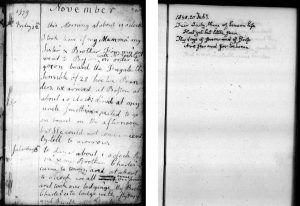

MHS Digital Volunteers who have tried their hand at transcribing historical documents with the MHS’s new crowdsourcing portal may already be familiar with the efforts of missionary Luman Boyden to bring aid and religious piety to struggling families in 19th-century Boston. Volunteers as well as readers of Laura Wulf’s blog post on Boyden’s journals will recognize both a genuine desire to help and a tone of judgment and disapproval toward the disenfranchised families.

Missionary societies hoped to bring reform to the poor of Boston through various kinds of projects, and nowhere is the mixture of sympathy and judgment more potent than in the reports of the Penitent Females’ Refuge Society. Boyden’s tone of disapproval sounds mild in comparison to that reserved for women who found themselves selling sex in the city.

The Boston Female Society for Missionary Purposes (later known as the Bethesda Society) was formed in 1800 by a group of women from Baptist and Congregational churches in the area. By 1819, a coterie of the women’s mission evidently saw it as their duty to extend “the purifying light of Revelation into the darkened and vicious places in our own city,” provided there were missionaries willing to place themselves in these “highways of sin” to minister to the “wretched outcasts” there.

Thus the Penitent Females’ Refuge was established, governed by a group of men, and supervised and run by female volunteers. The women’s missionary group became the “Ladies’ Auxiliary” to the Refuge. The goal of the Refuge was to mitigate prostitution and poverty among women in Boston.

It was decided that women could never be truly penitent and receptive to reform while residing in “abodes of iniquity” and was therefore determined necessary to remove them from their environment and their social contacts. A house was established for the women to stay, where they were provided basic education, ministered to in weekly Bible classes, taught practical skills such as sewing, and placed in housework positions.

The MHS holds copies of the Refuge’s annual reports from 1821-1908 as well as other pamphlets the Society printed promoting its good works to the public. Public promotion was not always easy. As the Society points out in an appeal to the public published in 1839:

The inherent difficulty of conducting a charity of this description, and the various embarrassments which must ever impede the best directed efforts, it is believed, are not duly estimated by the public in making up a judgment in reference to the beneficial results to be expected from such an institution as the Refuge; while, at the same time, these difficulties and embarrassments present the strongest claims upon benevolent interposition in behalf of the peculiarly debased, forlorn, and miserable class, to whom the door of every other refuge is effectually closed.

Nevertheless, the Society attempted to justify its existence by sharing success stories of women who had passed through its doors. The 1826 report relays the stories of current inmates at the time and the ways in which the Refuge improved their circumstances. Censorship and social mores prevented the Society from sharing too many prurient details of the women’s lives, lending to the reports a more suggestive vocabulary that sounds rather Victorian and overwrought to our modern ears.

Of one young woman, admitted four and a half years previously at the age of 17, it was reported:

A child of parents addicted to intemperance, she had neither precept nor example to restrain her from wandering into the paths of sinful indulgence. … Her temper is somewhat ungovernable, which has occasioned a difficulty in finding a suitable place for her out of the house. She has been at service about 10 months during the 4 ½ years, and is very faithful in the performance of her tasks. … To keep out of the vortex of vicious example, a young female, whose age and temper expose her to fall into the worst excesses, is surely a duty of Christians and of moral men.

Of another, a young woman from Maine, it was written:

No care appears to have been taken of her morals, and at the age of 14, her character was ruined. Despised and driven from her connexions, … she wandered to this city, where she entered on a full career of wickedness which brought her several times into the House of Correction, at the age of nineteen. … She was received here in November, 1824, and since her residence in the house, her disposition, which was naturally headstrong and passionate, has undergone a sensible revolution. … She has for some months given evidence of having experienced the grace of God upon her heart, and spares no pains to excite the attention of others to the concerns of their own souls. Is this a character, whom any father or mother would bid us let remain in the highway?

Despite referring to them as “inmates,” reformers at the Refuge expressed the goal to “govern the inmates as children in the best managed families are governed,” reasoning that “to throw around them the influence of kindness has the happiest effect in exciting their love and gratitude, and securing their respect and obedience.” Nonetheless, the Refuge reported the “elopement” of multiple women each year.

Similar organizations existed in New England as well as in other American cities, such as the New England Female Moral Reform Society in Boston and the Magdalen Societies of New York and Philadelphia. Treatment of women at similar societies in other cities seems to have varied. The Magdalen Society in Philadelphia, for instance, apparently found it necessary to build a large fence to prevent the escape of women who decided they didn’t want their help.

The New York Magdalen Society permitted only white women as the subjects of its benefaction; whether this was the case for the Penitent Females’ Refuge is not explicitly stated in its reports. Such organizations often admitted only young women who had recently found themselves among “vice and misery,” reasoning that they would be more amenable to reform. However, the Refuge reported women as old as about forty among its inmates.

Many scholars agree that 19th-century ideas about female sexuality were structured around a “Madonna/whore” complex wherein women were deemed either pure or debased. Only men, it was claimed, experienced sexual desire and enjoyment. Sexual feelings and activities were directed toward sex workers in order to preserve the perceived purity of wives and the family.

In one sense, the Penitent Females’ Refuge and similar organizations were radical in their assertion that prostitution was far from a necessary evil, that it was often a result of economic disenfranchisement, and that women who made their living with sex work could find themselves in more conventional livelihoods. On the other hand, the idea that women needed to be saved and their behavior controlled clearly played into these restrictive ideals.

Despite their deeply gloomy, judgmental tone, such sources may provide valuable insights into 19th-century attitudes about female sexuality as well as the daily lives and experiences of poor and working-class women.

Sources

Bethesda Society (Boston, Mass.). Annual reports of the Penitent Females’ Refuge Society and the Bethesda Society, 1821-1908. Boston, Mass.: Penitent Female’s Refuge.

New York Magdalen Society. First annual report of the executive committee of the New-York Magdalen Society. New York: Printed by John T. West & Co., 1831.

Ruggles, Steven. “Fallen Women: The Inmates of the Magdalen Society Asylum of Philadelphia, 1836-1908.” Journal of Social History 16.3 (Spring 1983): 65-82. https://users.pop.umn.edu/~ruggles/Articles/fallenwomen.pdf

Further Reading

Davis, Robert. “‘The men will not do it’: 19th Century Sex Work and Reform.” Lady Science. April 18, 2019. https://www.ladyscience.com/19thcentury-sex-work-and-reform/no55

Hobson, Barbara Meil. Uneasy Virtue: The Politics of Prostitution and the American Reform Tradition. New York: Basic Book, Inc., 1987.

Roberts, Nickie. Whores in History: Prostitution in Western Society. London: Harper Collins, 1992.