By Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

One of my colleagues at the MHS has made an fascinating discovery within our collections that I’m very happy to tell you about.

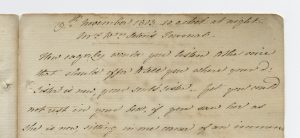

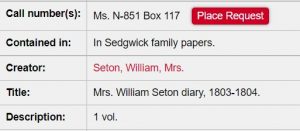

The massive collection of Sedgwick family papers at the MHS includes a small diary donated to us by Sedgwick descendant Elizabeth Gaskell Norton in 1924. The author of this diary was not Miss Norton, but a woman identified on its first page as “Mrs. Wm. Seton.” So this is how the volume was originally attributed in the MHS catalog.

Now, the MHS has been around for 231 years, and many women are identified this way in legacy descriptions (“Mrs. Husband’s Name”), particularly those donated to us so long ago. Unfortunately, an archivist processing such a large collection—in this case, about 70 linear feet—doesn’t usually have time to do the kind of in-depth analysis necessary to identify the unknown author of a single item.

But staff members at the MHS have recently spent a lot of time updating descriptions in our catalog, collection guides, and online presentations to bring them in line with modern standards. These efforts include, whenever possible, restoring a married woman’s full name. And fortunately for all of us, my colleague recently found the time to look more closely at this item. What she discovered surprised us both.

Mrs. William Seton was none other than Elizabeth Ann Seton, a.k.a. Mother Seton, the first American to be canonized as a saint by the Roman Catholic Church!

I won’t attempt to recap Seton’s life story here, but I would like to describe this volume in a little more detail. Coincidentally, the circumstances in which it was written are strikingly relevant today.

The bulk of the diary was kept between 19 November and 27 December 1803. Seton’s husband William suffered from tuberculosis, and the couple, hoping that a different climate might restore his health, had sailed from New York to visit friends in Italy. Their eight-year-old daughter Anna Maria traveled with them. When they arrived at the port of Livorno, however, they received a nasty shock.

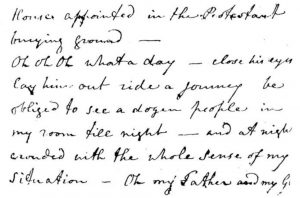

Due to a yellow fever epidemic in New York , the family was forced to quarantine for an entire month in a lazaretto, basically a centuries-old coastal prison once used to segregate individuals with bubonic plague.

The lazaretto was bleak, and Seton described her surroundings in suitably dramatic language: “high arched ceilings, like St. Paul’s – brick floor, naked walls & a Jug of water”; “a single window double grated with iron” with an armed guard outside; “a view of the open sea, & the beating of the waves against high rocks”; “bells for the dead” ringing at sunset.

She also described a kind of physical distancing that will sound familiar to us today, more than two years into our own pandemic. The Setons could speak to visiting friends through the barred door, but physical contact was prohibited. Items they had touched could not be touched by anyone else. One day, “an order from the Commandant was sent from our Boat which was received on the end of a stick – and they were obliged to light a fire to smoke it before it could be read.”

The details are terrific. My favorite image is Mother Seton, future saint, keeping warm in her cell by jumping rope! Her faith in God also sustained her. She passed the time reading, praying, singing hymns, and nursing her husband William. The diary is an amazing document of her religious beliefs shortly before her conversion to Catholicism in 1805.

Unsurprisingly, William’s tuberculosis grew worse during his confinement, and he lived just eight days after the family’s release, dying in Pisa on 27 December 1803. The diary breaks off at this point and skips to the middle of 1804, with entries by Seton about the death of her sister-in-law and intimate friend (her “soul’s sister”), Rebecca.

The provenance of the volume is confusing. During my research, I learned that the extant papers of Mother Seton are housed in a number of different repositories and were published in 2000 as part of the Vincentian Heritage Collections at DePaul University. Included is the text of this very diary. Apparently, there are several versions in Seton’s handwriting.

Unfortunately, a sample of her handwriting published in that journal proves that our copy was not written by her.

My best guess is that the volume held by the MHS was copied sometime in the early 19th century from the original, judging by omissions and errors in the text. Seton’s handwriting may have proved difficult to read in places. Our copy comes from the version held by the Sisters of Charity in Riverdale, New York (pp. 251-276, 307-310).

But who copied it and why? The Sedgwick family included many authors and historians, so it’s possible one of them conducted research on Seton. Perhaps it was copied by Jane Minot Sedgwick (1821-1889), who converted to Catholicism in 1853 and founded a Catholic school in West Stockbridge, Mass.

Whatever its provenance, we’ve grateful to have this volume as part of our collections, and we hope the improvements we’ve made to its description will help more researchers find it here.