By Gwen Fries, Adams Papers

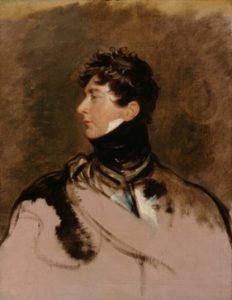

In 1815, when John Quincy Adams began his tenure as U.S. minister at the Court of St. James, King George III had for several years past been declared unfit to rule, and his eldest son was serving in his stead. The Regency Act of 1811 had vested the power of the Crown in the Prince of Wales, but in terms of etiquette—essential to a diplomat—Queen Charlotte was still the one to impress.

On 8 June 1815 Adams contacted the assistant Master of Ceremonies, Robert Chester, to get a refresher on royal protocol and court presentations. Adams was no stranger to court life, but with an indisposed king, his not-quite-widowed queen, nine surviving princes and princesses, and a Prince Regent and his daughter to consider, the protocol was perplexing. “I asked whether it was usual for the foreign Ministers to be presented separately to the Princes of the Royal family,” Adams recorded in his diary, “and when and to whom visits of form were to be paid— He said that after having an Audience of the Queen, and not until then, it would be proper to call at the Residences of all the Princes.” Chester guessed that Charlotte would return to London in the course of a week and would give the Adamses an audience then.

Adams was barred from visiting the other princes’ residences until he had presented himself to the Queen, but he was invited to Carlton House for an audience with the Prince Regent. Chester added that should Adams run into any of the Regent’s brothers at Carlton House, he was permitted to make a personal presentation.

After waiting an hour and a half, Adams was introduced into the Prince’s closet. “He stood alone; and as I approached him, speaking first, said, ‘Mr Adams, I am happy to see you.’” Adams presented him with a letter from the U.S. government. “The Prince took the Letter, and without opening it, delivered it immediately to Lord Castlereagh.” The Prince Regent asked about the elder John Adams as well as John Quincy’s impressions of Ghent. Castlereagh tactfully drew the conversation to a close, and they withdrew from the chamber. Adams was then introduced to the Duke of Clarence—the future William IV—making that two future kings in one levee.

But it was not kings he needed, it was the Queen. Nearly five months later, John Quincy and his wife Louisa were still waiting for an audience. On 26 October, Adams knocked flat with a painful inflammation in his eye, Queen Charlotte finally held a drawing room. Adams had to beg out due to his infirmity.

At the close of 1815 and the start of the new year, John Quincy was still waiting for an audience. On 31 January 1816, Adams heard that Charlotte was in London, “but not for the transaction of business.” His hopes were raised on 1 March when the newspapers announced that the Queen would hold a drawing room within the week. John Quincy immediately reached out to Lord Castlereagh, seeking an introduction for himself and for Louisa to Her Majesty. Castlereagh dashed his hopes, revealing that the announcement was mere gossip. To add insult to injury, later that week John Quincy was passed on the road by Queen Charlotte on her way back from Windsor.

Two weeks later, the happy news finally arrived: “The Queen will hold a Drawing-Room, next Thursday, the 21st. at 2. O’Clock at Buckingham House.” Preparation began immediately.

Early in the morning on 21 March, John Quincy and Louisa traveled to London to dress for their presentation. There was one final hitch. John Quincy discovered his audience was scheduled after the drawing room, meaning he could not attend with his wife. “Mrs: Adams would have been obliged to go alone, would be a stranger there,” Adams recorded in his diary. “I concluded to go with her and wait.”

John Quincy waited downstairs for more than two hours. “While I was there, the Duke and Duchess of York, passed through it, going by a private passage, to the drawing-room, and the Duke of Sussex, and the Duke and Princess Sophia of Gloucester, in coming from it. The Duke of Sussex stopped and spoke to me.” Adams had heard positive things about Sussex and was favorably impressed, even sharing a laugh with the Queen’s sixth son.

Finally Adams’s moment had come. “The Queen was standing about the middle of the Chamber. Just behind her at her right hand stood the Princess Augusta, at her left the Princess Mary—further back several Ladies in waiting, and the Duke of Kent in Military Uniform.” Adams performed his prepared speech. Charlotte asked after John Quincy’s health, and ever the keen botanist, inquired about the climate of the United States. “She asked me whether I was related to the Mr Adams who had been formerly the Minister to this Country, and appeared surprized when I answered that I was his Son,” Adams wrote. “She forgot that I had given her the same answer to the same question twenty years ago; and had apparently no recollection that I had ever been presented to her before.”

The introduction made, Adams could perform his diplomatic duties unhindered. He immediately visited the residences of the Duke of York, the Duke of Cumberland, the Duke of Gloucester, and the Duke of Clarence. He routed his carriage past Kensington Palace so he could also call at the apartments of the Duke of Kent and of the Duke of Sussex.

A few weeks later, on 4 April, John Quincy was able to attend his first drawing room. “The forms of this presentation are different from those of the Circles on the Continent,” Adams noted. “The Queen does not go round the Circle. She takes a stand, before a Sopha— The persons attending the Drawing Room, go in from the adjoining Hall; go up to her and are spoken to her in succession, after which they pass onto the Princesses and Princes who stand at her right hand, each of whom speaks a few words, and then the person files off by another door, and goes down Stairs to go away.”

His first drawing room done, Adams returned to his lodgings, changed out of his fancy clothes, and settled down to something much more to his taste—a stack of Boston newspapers.

The Adams Papers editorial project at the Massachusetts Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the generous support of our sponsors. Major funding of the edition is currently provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, and the Packard Humanities Institute.