By Hobson Woodward, Series Editor, Adams Family Correspondence

John Adams traded the political tumult of Washington, D.C., for the songs of birds in the fields of his beloved Massachusetts homestead of Peacefield in February 1801, leaving behind the demanding routines of the presidency to tend crops by day and read and write letters in the evenings. The same was true of Abigail Adams, who no longer hosted leevees for the capital elite as first lady and returned home to oversee her Quincy household of servants. Abigail settled a bit more uneasily into her new routine, as shown by her writings in the latest publication by the Adams Papers editorial project: volume 15 of Adams Family Correspondence. Abigail’s efforts to transition to a new phase of life included working through a subject that gnawed at her a bit—the family’s long and complicated relationship with Thomas Jefferson, the man who just defeated her husband in a fraught election to become the nation’s third president.

The documentary evidence of Abigail’s extended “exit interview” with Jefferson began when she was still first lady with a “curious conversation” they had over dinner in the closing days of her husband’s administration, an exchange she transcribed and sent to her son Thomas Boylston Adams. The two talked party politics and foreign policy, but she demurred when Jefferson attempted to raise the topic of the election. Abigail had no such compunction when she wrote an essay on politics soon after returning to Peacefield, a document that is featured in this volume of Adams Family Correspondence. Two written works prompted the drafting of the essay—a letter from her son John Quincy Adams to his father laying the son’s vision of the debt owed his father by the nation for a lifetime of public service. The second was the inaugural address of Thomas Jefferson. Writing as “a Lover of Justice,” Abigail denounced the positive press coverage of Jefferson’s address, excoriated John’s most virulent critics, and drew on the language of her son’s letter to laud the accomplishments of her husband’s presidency. The piece was apparently never published and it’s not clear whether Abigail penned it for personal or public purposes, or both.

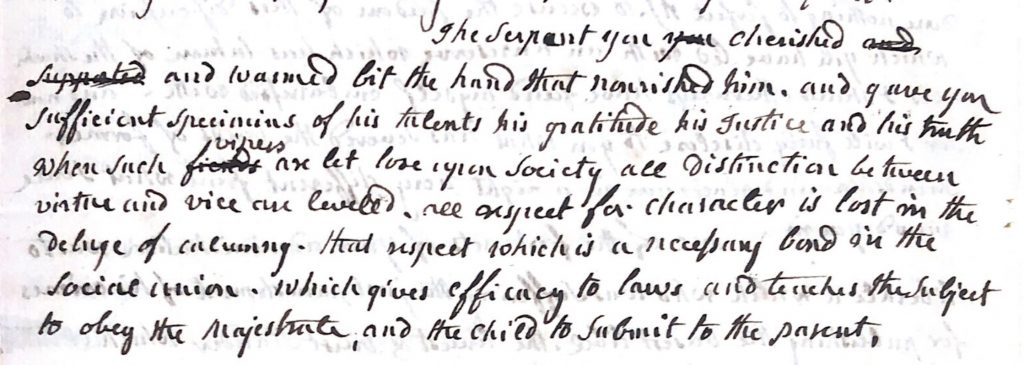

The papers left behind by the Adams family, a centerpiece collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society accessible to the world through an ever-expanding array of digital portals, reveal that three years later Abigail found closure of sorts in an exchange of letters with Jefferson. The renewal of correspondence between the two in 1804 began with little expectation of political debate, when Abigail sent Jefferson a letter of condolence upon the death of his adult daughter, Mary Eppes. Years earlier the Adams matriarch had cared for Mary as a child and she offered Jefferson the empathy of a parent who had herself lost an adult child with the 1800 death of Charles Adams. Jefferson responded with a letter of thanks that ruminated on his friendship with Abigail and John, mentioning almost as an afterthought that their friendship endured despite John’s “personally unkind” appointment of Federalist judges in the closing weeks of his administration. Abigail responded that she had not intended to delve into politics, but Jefferson’s comment took “off the Shackles I should otherways have found myself embarrassed with.” The result was an exchange that would extend to seven letters, in which the two talked out their differences. Abigail defended John’s judicial appointments as his constitutional duty, moving the conversation to her displeasure with revelations that Jefferson had made payments to notorious Adams critic James Thomson Callender. What Abigail characterized as subsidies to an unprincipled newspaperman, Jefferson cast as unrelated charitable assistance to an indigent immigrant. Abigail couldn’t help but point out that Callender had recently turned on Jefferson. “The Serpent You cherished and warmed, bit the hand that nourished him,” she wrote. The correspondence concluded after Abigail broached Jefferson’s failure to renew John Quincy’s appointment as a federal bankruptcy commissioner, a reappointment opportunity Jefferson claimed had escaped his notice. Abigail then ended the exchange on a friendly note.

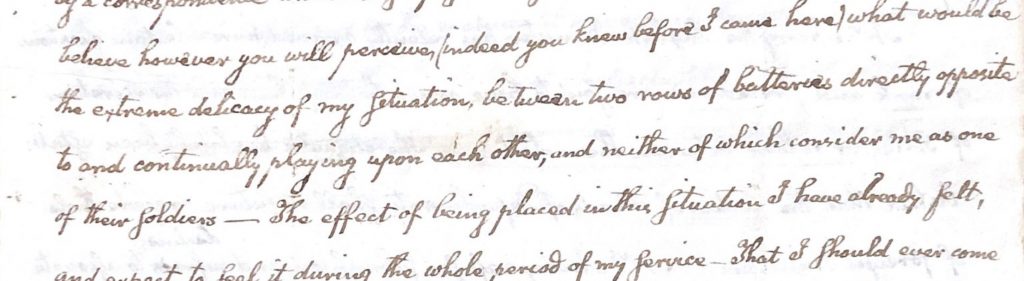

By the time Abigail was querying Jefferson on John Quincy’s public service opportunities, the Adams son had long since moved on. The bankruptcy commission had been a Boston assignment while he resided in the city as a member of the state legislature. John Quincy had since become a U.S. senator and argued cases before the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington, D.C., placing him at the center of political life as the most prominent member of a new generation of Adams public servants. John Quincy didn’t have to wait long to face some of the political turmoil experienced by his father. The first major item on the agenda after his swearing in was the Louisiana Purchase. John Quincy first angered Democratic-Republicans by joining in opposition to the purchase, then set off Federalists by voting to fund the purchase on the presumption that a constitutional amendment would be simultaneously considered. The Senate refused to bring the constitutional issue to the floor, prompting John Quincy to oppose later Louisiana bills. Son wrote to mother that acting independent of party was akin to standing “between two rows of batteries directly opposite to and continually playing upon each other, and neither of which consider me as one of their soldiers.”

John Quincy was not the only member of his family getting used to life in Washington, D.C. When he returned to the United States in the fall of 1801 after seven years as a diplomat in Europe, he was joined by his wife, Louisa Catherine Adams, and their infant son, George Washington Adams. Louisa Catherine grew up in England as the daughter of an American father and British mother, and she brought the experience of London society and Berlin court life to bear in her new position as the wife of a United States senator. Louisa Catherine emerges in volume 15 of Adams Family Correspondence as a fresh voice, keeping her mother-in-law informed of the latest developments in parlor politics in the nation’s capital, one of several members of the next generation of the Adams family who will join the conversation as the publication of family letters continues.

The Adams Papers editorial project at the Massachusetts Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the generous support of our sponsors. Major funding for Adams Family Correspondence is provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, and the Packard Humanities Institute.