By Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

The MHS recently acquired a letter dated 26 October 1848 from a woman who signed her name simply “E.” Based on subject matter alone, the letter was obviously a great find and a natural fit for our collection, but it became even more interesting the more I looked into it. I was able to make a number of fascinating historical connections, and I couldn’t resist sharing the story with Beehive readers.

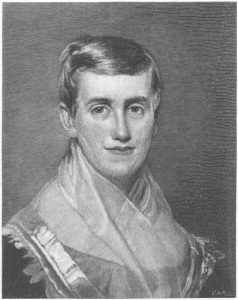

“E” was Emeline Goodwin, born Emeline Philleo in the small town of Amenia, N.Y. on 13 April 1813. Her mother died when she was a teenager, and in 1834 her father married Prudence Crandall, a remarkable Quaker, abolitionist, and suffragist. Crandall, once imprisoned for establishing a school for young African American women, was named Connecticut’s state heroine in 1995! She deserves a Beehive post of her own, but for now I’ll just include her picture here, from the MHS’s Portraits of American Abolitionists collection.

When she was 19 years old, Emeline married 51-year-old Col. John Marston Goodwin, and the couple had four children: John Marston Goodwin, Jr.; Elizabeth Wheeler Goodwin; Lebaron (or LeBaron) Goodwin; and Francis “Frank” Goodwin. John, Sr. died in 1845, when little Frank was just eight months old.

Now a 32-year-old widow with four young children to support, Emeline quickly got to work. By April 1846, she’d secured a job at the Concord, Mass. home of none other than Ralph Waldo Emerson, apparently through the intercession of his wife Lidian, who was not well enough to take care of the housekeeping. A biography of Emerson explains how the family

“tried the novel experiment of living in their own house as boarders of a Mrs. Marston Goodwin, who was allowed to bring in other boarders, as well as her four children. […] The experiment, lasting apparently from May, 1846, to September, 1847, left Lidian with the conviction that Mrs. Goodwin was “born for the blessing of others” and was “thoroughly tender & self sacrificing.” (p. 311)

The arrangement ended when Ralph Waldo Emerson left for England, and once again Emeline had to look for work. Her oldest son, 14-year-old John, Jr., was in school, probably at the Connecticut Literary Institute in Suffield (now Suffield Academy). She needed to find a new situation that would not only pay her mounting bills, but also allow her three younger children to live with her.

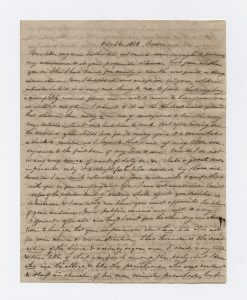

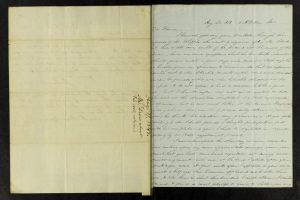

This is the backstory behind the MHS’s new acquisition, pictured above, a letter Emeline wrote on 26 October 1848 to her brother Calvin Wheeler Philleo. Her primary purpose for writing was to tell him about her new job as matron at what was then called the Perkins Institution and Massachusetts Asylum for the Blind. She described the job as “one of great care, labor [and] confinement” with “many disagreeable features no doubt” but nonetheless “very attractive.”

The position had recently been vacated by another fascinating woman, Eliza W. Farnham, a feminist, author, reformer, and former matron of the women’s prison at Sing. Emeline was flippant about “the celebrated Mrs. Farnham,” calling her “the Mrs. Fry of America.” (Elizabeth Fry was a British prison reformer.) Emeline wrote that Farnham had resigned “from dislike of the situation as not suited to her style of genius.” That may have been true, but it also happens that Farnham’s husband died and left her land in California.

While doing my research, I happily stumbled across a bound volume of correspondence of Samuel Gridley Howe, founding director of Perkins, part of the Perkins collection digitized at the Internet Archive. Included is an 1848 letter from Goodwin to Howe asking about the position and describing her circumstances; several letters of recommendation on her behalf, including one from Emerson commending her “intelligence, indefatigable energy, high sense of justice,” and “kind heart”; and other letters by and related to her.

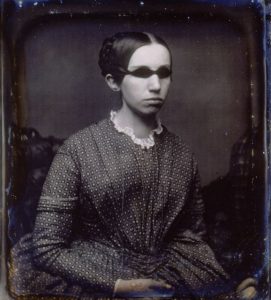

One of the many students Emeline Goodwin worked with during her tenure as matron at Perkins was the renowned Laura Bridgman, another woman worthy of more space than I can give her here. According to a biography of Bridgman, she and Goodwin read together, and Bridgman considered her a “very dear friend.”

Emeline’s letter is four pages long and covers a wide range of other subjects, including her children’s education, Calvin’s career in state politics, the growth of the anti-slavery Free Soil party, even the celebration of the Cochituate Aqueduct. It’s a great addition to the MHS collection.

The letter also introduced me to an amazing network of women who influenced each other’s lives in very profound ways: Emeline Goodwin, Prudence Crandall, Lidian Emerson, Eliza Farnham, Laura Bridgman, and others.

Emeline Goodwin remarried in 1853 to Charles King Whipple, an apothecary and agent of the American Anti-Slavery Society. She died on 5 May 1885 and is buried with her first husband and three of her children at Oak Grove Cemetery in Plymouth, Mass.