By Jessie Vander Heide, Ruth R. Miller Fellowship

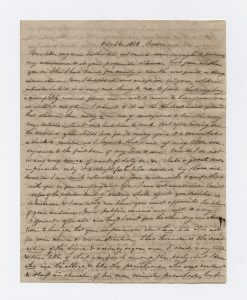

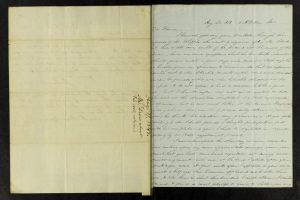

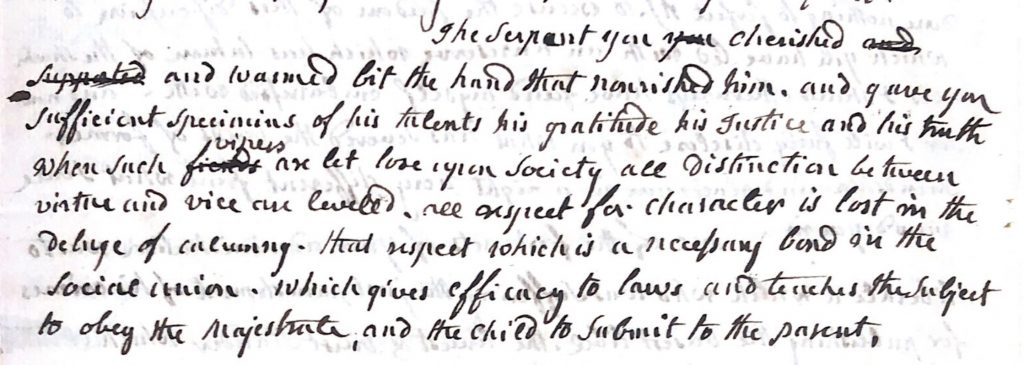

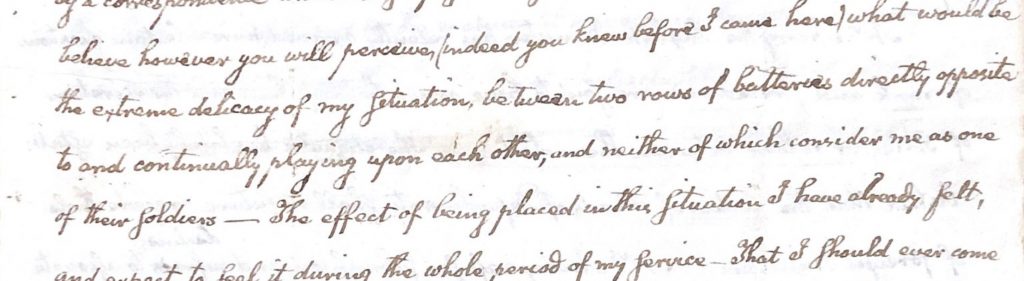

Writing to her niece Sarah White Shattuck, who was a student at Bradford Academy in Haverhill, Massachusetts in the 1840s, Sarah Baxter advised her niece to exercise caution when forming new relationships at school: “The company we keep is exercising a constant influence over us, how necessary then is it that it should be good. Cultivate the good will of all, the friendship of few.”[1] Shattuck’s aunt was not the only family member who worried about, and offered advice on, Shattuck’s new social situation at school. Sarah’s father Lemuel Shattuck similarly feared how his daughter’s school companions might influence her. Desiring that his daughter “should have as good a companion, and be under as good influence [at Bradford Academy] as is possible to be,” Lemuel guarded his daughter’s social relations. “Greatly concerned” that some of Sarah’s classmates were a “disadvantage” to her improvement, Lemuel instructed Sarah on how to find a roommate while attending school and advised her that he, along with her teachers, would decide with whom she was to room and befriend.[2]

Sarah White Shattuck was one of many middling-class young women who had the opportunity to receive an academy education in the early republic and whose family was concerned about her social development at school. Beginning in the post-Revolutionary era, young women were newly leaving home to attend female academies, escaping parental authority, and establishing their own extra-familial social relations for the first time. Post-Revolutionary women were raised with newly broadened horizons, but new opportunities also posed, according to many adults, new threats to American womanhood. Many parents and educators especially worried that young women’s school attachments might become too intimate and might distract young women from their future civic duties as wives and mothers. My current project examines both the relationships that young women cultivated with one another at school and how parents and educators attempted to guide students’ intimacies. Collections held at the MHS provide a window into 19th-century worries about schoolgirl intimacies and adults’ strategies to guide and guard academy students’ relationships.

To allay fears about young women forming pernicious relationships at school, educators worked tenaciously to create “safe” and “improving” social spaces for students. Educators at reputable New England academies, including Bradford Academy and Abbot Female Academy, promised that they were as invested in young women’s moral and social wellbeing as they were their intellectual development and they instituted designs, rules, and routines that worked to shape and regulate the social activities and relationships of students.

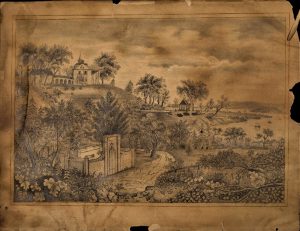

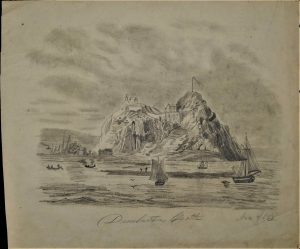

School catalogues and institutional records show that educators used several strategies to govern young women’s relationships. School rules instructed that students were prohibited from entering one another’s rooms without teachers’ or guardians’ approval, and that students could not talk or congregate in school hallways. This meant that students faced difficulty developing relationships outside of more formal, public settings, such as in the dining room or in class (spaces that teachers carefully surveilled and arranged through seating charts). The location and architecture of academies also worked to limit young women’s ability to move about and socialize. Educators frequently built female academies close enough to urban areas that travel to them was convenient, but distant enough from cities that students were not drawn into dangers that they believed lurked there.[3] Students were only granted permission to leave academy grounds when accompanied by a chaperone. Further, most female academies constituted only one or two large buildings, with each structure having a single main entrance and stairwell, a reality which provided students with little escape from watchful eyes and few places of retreat. Finally, academy leaders designed school schedules in ways that limited female students’ abilities to interact socially and/or in private with one another. Students’ daily lives were regulated by rigorous schedules. Sarah White Shattuck and Katharine Lawrence described their daily routines at academies as being so busy that they had little time to do “anything except reading and studying.”[4] Even when students were granted “recreation” time, it was meant to be spent in writing compositions or doing chores such as cleaning and repairing clothes.[5] With such school designs, educators could stipulate with whom, how often, and in what context young women could build relationships (at least without risking punishment!).

To keep anxious parents informed about their daughters’ social and moral improvement, teachers sent home monthly reports that documented students’ behavior and school standing.

Students frequently complained about how academy rules and schedules inhibited their social lives and female friendships. Frustrated that school rules stunted her social impulses, Hattie, a Bradford Academy student in the 1840s, bemoaned to her friend Jennie: “In the evening we are obliged to keep study hours, we cannot go out of our rooms or speak to any of the girls, if we do, it is a violation and we have to hand it in as such.”[6] Another Bradford student complained about being “bound by Bradford rules” and looked forward to “enjoying freedom” when the term ended.[7] With a sense of humor, some students referred to the academies they were attending as “prisons,” “nunneries,” and “asylums.”[8]

Despite the fact that young women felt academy regulations were sometimes overbearing and restricted student social life, many of them considered their schooldays to be some of the happiest in their lives, and they developed deeply intimate bonds with fellow students. Describing her experience at Bradford, Sarah White Shattuck explained “I think I never attended or ever heard of a school where there were so few young ladies you would dislike and where there were so few that you would not wish to associate with.”[9] Similarly praising her experience at Abbot Female Academy, Mary Elizabeth Jenks wrote home: “I do not think it would be possible for me to enjoy myself better any where than I have here.” “Andover,” Jenks wrote, “is certainly the most delightful place in the whole world.”[10]

[1] Sarah Baxter to Sarah White Shattuck, May 6, 1841, Sarah White Shattuck Papers, MHS.

[2] Lemuel Shattuck to Sarah White Shattuck, September 3, 1841, Sarah White Shattuck Papers, MHS.

[3] Susan McIntosh Lloyd, A Singular School, Abbot Academy 1828-1973 (Andover: Phillips Academy, 1979), 100; A Catalogue of the Officers and Students of Gilmanton Academy, 1849-50 (Concord: McFarland & Jenks, Printers), 23, MHS.

[4] Journal of Katharine B. Lawrence, January 23, 1847, Lamb Family Papers, MHS; Sarah White Shattuck, April 24, 1841, and February 5, 1844, Sarah White Shattuck Papers, MHS.

[5] Delia Warren to Samuel D. Warren, February 16, 1839, Warren-Clarke Papers, Box 1, MHS; Hannah Warren to Samuel D. Warren, October 12, 1842, Warren-Clarke Papers, Box 2, MHS; Delia Warren to Samuel D. Warren, November 4, 1842, Warren-Clarke Papers, Box 2, MHS.

[6] Hattie to Jennie, May 5, 1846, as recorded in Jean Sarah Pond, Bradford: A New England Academy (Bradford, MA: Bradford Academy Alumnae Association, 1930), 152-153.

[7] Hannah to Martha Dalton Gregg, December 22, 1843, Martha Gregg Tileston Papers, Box 1, MHS.

[8] Please see, for example, inscriptions in friendship albums: Nancy Richardson Symmes Remembrance Book, 1834-1839, MHS.

[9] Sarah White Shattuck to her parents, May 20, 1841, Sarah White Shattuck Papers, MHS.

[10] Mary Elizabeth Jenks to her mother, July 30, 1835, William Jenks Papers, Box 37, Folder 8, Mary Elizabeth Jenks, Correspondence from Andover, MHS.